Visiting the Cook Islands to join the country’s first-ever Pride celebrations, Steffen Michels discovers that alongside its exquisite beaches, this once-polytheistic Polynesian destination has a rather more complex texture than some might expect.

There’s a remote corner of the South Pacific where it’s possible to join the ranks of time travellers. All it takes is to board a flight in Sydney and head east to Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands. When I do, I leave Australia at 9.30pm and arrive in Rarotonga at 7.15am the same day, rewinding a remarkable 20 hours in return for just six in the air. It’s a quirk of the International Date Line, of course, which lies between the two destinations. And yet, when I first arrive in the Cook Islands, nearly stumbling over a chicken in the country’s sole international airport as a flower garland is placed around my neck, I feel as though in some ways I have indeed gone back in time.

Rarotonga, the main volcanic landmass of this 15-island-strong archipelago nation between Fiji and French Polynesia, offers quintessentially South Pacific impressions on a conveyor belt. There’s only one ‘proper’ street here and you can drive around the island in 40 minutes (it helps that there isn’t a single traffic light on Rarotonga or, for that matter, anywhere in the country). You won’t need GPS either. Should you chance to look, you’d only find yourself located on a tiny piffling speck in the middle of an ocean that covers nearly this entire side of the globe. At that scale, only Australia and Antarctica can be seen clinging to its curving blue sides, as if to remind you that the world isn’t all water.

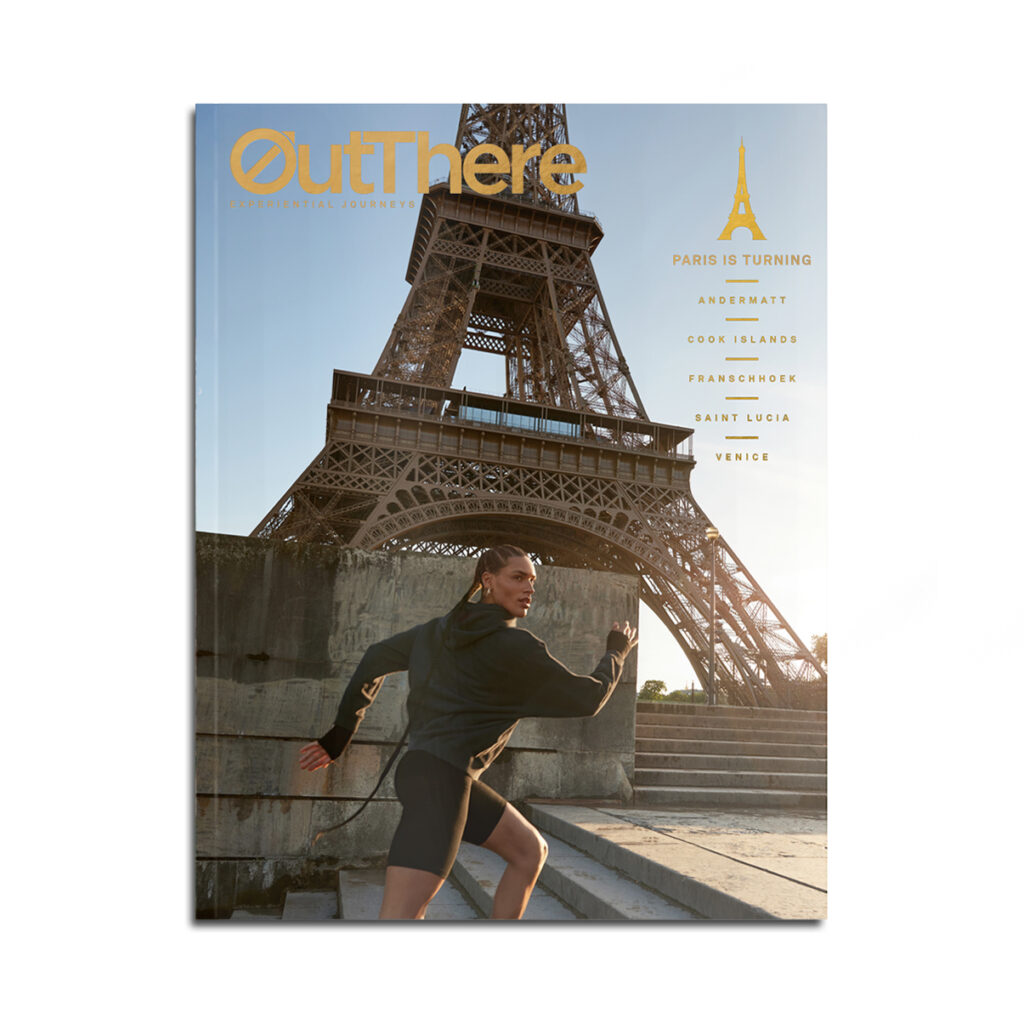

This story first appeared in The Paris is Turning Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

On these small islands, views and sounds of the sea are inescapable wherever you go. So, too, are the friendly locals, all ‘aunties’ or ‘papas’, the former wearing elaborate wreaths of flowers in their hair while lingering over leisurely lunches that last well into the afternoon. The world feels at peace here, from Rarotonga’s glistening lagoon to the iconic rock spire of Te Manga, the island’s second-highest mountain. And it’s not hard to believe that the country’s highest elevation isn’t a mountain in the traditional sense, but the stacks of food Cook Islanders and visitors pile up at regular buffet dinners – papaya salad, cassava chips, banana poke and rukau, a creamy dish of taro leaves (a root vegetable) cooked in coconut milk – a staple green-vegetable dish here.

There are many such buffet events during my visit to celebrate the nation’s first-ever Pride festival, Anuanua, exactly one year on from the decision to decriminalise homosexual acts between men (female homosexuality, as in many other parts of the world, was never against the law). Not only is this a turning point for the remote country, it also echoes its earlier ways, as same-sex relationships were once integrated into the Cook Islands’ social culture. As were the transgender women known as akava’ine (‘behave-like-a-woman’), who with varying denominations continue to be accepted subcultures across Polynesia, alongside Samoa’s fa‘afafine and Fiji’s vakasalewalewa.

In 1821, however, English missionary John Williams brought the gospel to the Cook Islands and with it discriminatory colonial legislation that all but wiped out the islands’ polytheistic belief system, replacing it with Christianity, to this day the country’s dominant religion. The church, of course, opposed decriminalising homosexuality in the Cooks, decrying the idea as foreign interference with local values in a display of irony that’s both staggering and classic Christian. But today the islands seek to be a modern nation, and nowhere more so than in Rarotonga, where I spot rainbow flags outside bars, restaurants and a furniture shop. Nor are lines of allegiance here black and white. At one of the Pride events I attend, the buffet has been prepared by the local church. “They do good catering,” one organiser tells me, “and they were the cheapest too.”

The bluest lagoon

While the Anuanua festival is remarkable in scale, comprising design competitions, panel discussions, a theatre production (Pane Provocations by award-winning local playwright Teherenui Koteka) and more, my South Seas quest also takes me to Aitutaki, an even smaller island just 50 minutes north of Rarotonga by plane. Unlike other destinations whose attractions must be discovered bit by bit, Aitutaki assiduously promotes its paradise-within-a-paradise status on visitors’ arrival. There’s the ukulele stage by the departure gate, the small plane reminding you of the short landing strip, and the bubbly flight attendant, who tells me she plucked the red hibiscus flower I admire in her hair at Rarotonga airport.

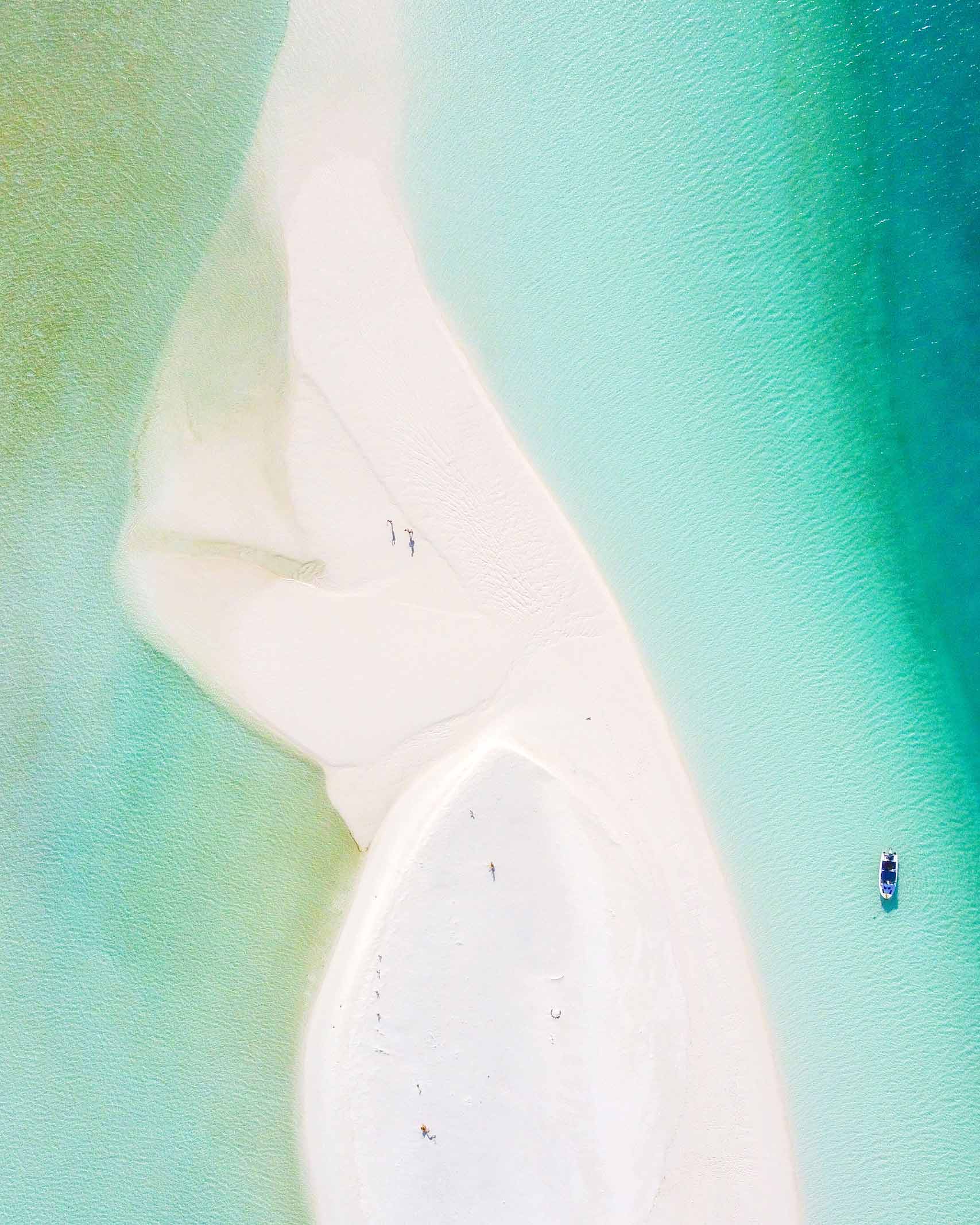

Even by South Pacific standards, Aitutaki, a mini archipelago in its own right, is breathtaking. From above, the cluster of islets is triangle-shaped, with a huge and stupefyingly cyan-coloured lagoon at its centre. The water here is of a shade beyond all those I’ve seen even in Indonesia, the Caribbean and the Maldives. It borders on luminescent, and a thin strip of pearly white sand studded with yellow-tipped palm trees weds it to the endless, open sky above. If the moniker Island of the Gods hadn’t been claimed by Bali, I’d be tempted to call this place just that.

Be that as it may, the influence of at least one god is certainly palpable here. It was in Aitutaki that the nation’s first-ever church opened in 1836 and, intrigued to understand this far-flung place’s specific cultural mélange, I attend a Sunday morning service. It’s the highlight of the island’s weekly social calendar and I sit beneath a ceiling adorned with historical decorations imported from England among mostly elderly locals – the women clad in pastel costumes with matching hats and the Cook Islands’ famous black pearls, the men in dapper suits. While the service is joyful and celebratory, and visitors (‘friends’) are welcomed to the island by the priest, I sense that the church holds Aitutaki life in its grip.

On Sundays, most stores stay shut and planes can’t land before noon. If you’d like to beat the heat with an early morning tour, those can’t happen before midday either. Alcohol isn’t on sale on Sundays, and sporting events on any day of the week must be approved by the church. Joining a boat tour or a buffet dinner at your hotel? Expect communal prayers. None of these things is necessarily bad. It’s just that, having travelled about as far as I possibly could from the UK, I’d hoped to be immersed in Polynesian folklore, not Bible verses familiar from childhood.

Sleeping giants

To sample said folklore, I enlist the help of local tour guide Ted Tavai, who, naturally, only works afternoons on Sundays. Ted is a fountain of knowledge. Through him, I hear the story of how Cary Grant, Marlon Brando, John Wayne and others were once stranded on Aitutaki when their plane ran into engine problems on the Coral Route, a legendary air itinerary that strung together the South Pacific’s dreamiest destinations in an uber-glamorous holiday for the rich and famous of the day. “Televisions didn’t exist on the island back then,” says Ted, “so when the government asked the people of Vaipae village to house the famous visitors, they were perfectly regular Joes to them.” Although it’s confirmed the incident occurred, I can’t find definitive evidence to prove that Brando and co were aboard the stranded aircraft. Charming beyond measure in any case, the village to this day proudly welcomes visitors with Hollywood-themed signs here and there.

As we make our way further into the island’s interior, Ted shows me several marae. Dating back as far as the 13th century, these sacred places marked by stones were once used for communal and ceremonial purposes. Marae appear across Polynesia, attesting to the region’s remarkable early sailing culture and suggesting a shared trans-Pacific identity that spans all the way to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). There, the local expression of ahu, stone tombs on which religious sculptures were placed, are the plinths on which many of the world-famous moai statues stand. Though the marae of Aitutaki are less monumental, they exude a powerful allure – one in particular even while hidden deep within the tropical forest. A collection of luxuriantly overgrown stone slabs, it’s a sacred site that’s been around for hundreds of years and was once used, a 2004 dig confirmed, for animal sacrifices and offerings to the gods.

Given the site’s current state, I reckon the gods are asleep. “Sadly, it’s been neglected since the pandemic,” says Ted, “which makes it harder to access and show to visitors.” That marae continue to dot the Cook Islands at all, however, is testament to locals clinging to a part of their culture that was under threat from Christian settlers, who, allowing for no other gods, dismantled rock constructions and stone statuary across Polynesia. It’s clear that Ted himself is fascinated by this part of the Cooks’ history and passionate about safeguarding it for future generations. As we bid farewell to the last marae of our tour, he tells me that, “to their credit, the early missionaries also eradicated ritualistic cannibalism on the islands”. I spot appreciation on his face. “And they stopped men from having several wives.” At that, his facial expression seems to become more ambiguous.

Dancing with the gods

Returning to Rarotonga, I still wonder what happened to the mighty gods once revered across the archipelago, representing everything from elements to sea and mountains. I learn more when I meet Cook Islander Kura Happ and her Italian other half Jacopo Dozzo, who take me on a mountain hike. En route, the pair demonstrate their astonishing knowledge of the local ecosystem with each step, explaining the medicinal properties of fruits we pluck and taste – custard apples, lemon-drop mangosteens, ice-cream beans, breadfruit, noni berries (which rival durians for their blue-cheese-like flavour) and rare chupa chupa, which fetch up to $200 a pop in China.

Only when we get to the top do I get lost in the view. Rarotonga’s famous Needle rock formation is straight ahead and verdant valleys lie all around us. In the distance, the island’s turquoise lagoon contrasts with the deep-blue sea beyond. That’s when Kura picks a sleeping hibiscus flower to show me how to suck the sweet nectar from the base of the bloom. And that’s far from the only thing I learn from her. Judging by the story she recounts of a legendary female warrior from another Cook Island, Atiu, who used coconut tree inflorescences as weapons, and her tips on how to make a Polynesian grass skirt, it’s clear that Kura is in touch with her culture. So much so that I still think about it as I laze on the beach later that day.

During my time here, I am struck by the ingenuity the people of this nation display in response to their environs. Their arts and crafts borrow from nature; their song and dance tell of ancient tales and wisdoms. And, despite encroachments in the name of ‘faith’, these impossibly exotic islands with their dazzling lagoons, floral wreaths and tokere drums look and feel like nowhere else I’ve ever been. Not even the sleeping marae, which may ultimately succumb to the jungle, eclipse that.

Omnipresent, too, is a light-hearted sense of humour here. It’s on full display at the final major event of Anuanua Pride, the Miss Thunderhips competition at the National Auditorium. On stage, six akava’ine contestants make their grass-skirt-clad hips shudder with such rage that the mountains of food in the buffet start to tremble in terror. Then, actual thunder makes an appearance, as sudden rainfall engulfs the venue, which is only partially roofed. A hefty breeze blows through the auditorium. Silvery moonlight scurries across the sea. Waves crashing on the beach drown out the music. And the crowd turns to look through a gap between two tarpaulins above. There, the mountains of Rarotonga tower in the distance, gazing down upon dancers whose gravity-defying hips have a life of their own. “One way or another,” I think to myself, “I sit here among gods tonight.”

Photography by Daniel Fisher, Alexandra Adoncello, Ben Teina, Sean Scott, Johnny Hendrikus, Club Raro, Steffen Michels, Angel Productions ANUANUA, Kieran Scott, and courtesy of cookislandspocketguide.com and Cook Islands Tourism

Get out there

Do…

… treat yourself to a sunset dinner at Rarotonga’s lesbian-owned Antipodes, which boasts an extensive fine-dining menu. More casual but totally scrumptious is Avatea Café on Aitutaki.

… go beneath the surface with Dive Rarotonga – you’re guaranteed to spot all sorts of rainbow-coloured fish and beautiful green turtles. But, for Mama Nature’s sake, never touch the animals – even the friendly ones – no matter how tempting.

… stop by the Te Ara Museum for an introduction to the Cook Islands’ history and culture. We’d argue that the gift shop is excellent, too, selling locally made arts and crafts of superb quality.

Don’t…

… expect top-tier luxury. There are no big hotel brands here, and accommodation isn’t as glamorous as what you’ll find elsewhere. That said, between a beach and a buffet, you’re in for authentic barefoot luxury that’s in a class of its own.

… just stay on Rarotonga. Aitutaki’s impossibly blue lagoon must be seen to be believed, and the island of Atiu is so off the beaten track, visiting might just feel as though you have it all to yourself.

… decide it’s too much trouble to come here. The Cook Islands are far from most parts of the world, but they’re a veritable paradise and can be easily combined with a trip to Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii or French Polynesia. You won’t regret visiting.

The inside track

Kura Happ and Jacopo Dozzo own eco tour business Ariimoana Walkabouts. Kura is a renowned musician and South Pacific specialist for Lindblad/National Geographic expeditions, while Jacopo is a travel agent by trade and a tour guide by passion.

Eat

Try the local breakfast of maroro tunutunu – barbecued flying fish – at Rarotonga’s Punanga Nui market. It’s served with fresh coconut cream, boiled arrowroot, a squeeze of lime and – if you dare – fiery chillies.

Walk

Hike Rarotonga’s Takuvaine Valley, behind Avarua Township, where you can see traditional terraces of taro (a root vegetable), patches of watercress, ancient chestnut trees and ūtū, a rare mountain banana.

Mingle

Catch up with local gossip at Rarotonga’s Game Fishing Club, just outside Avarua, where the atmosphere is relaxed, and mingling with Cook Islanders around the best pool table on the island is priceless.