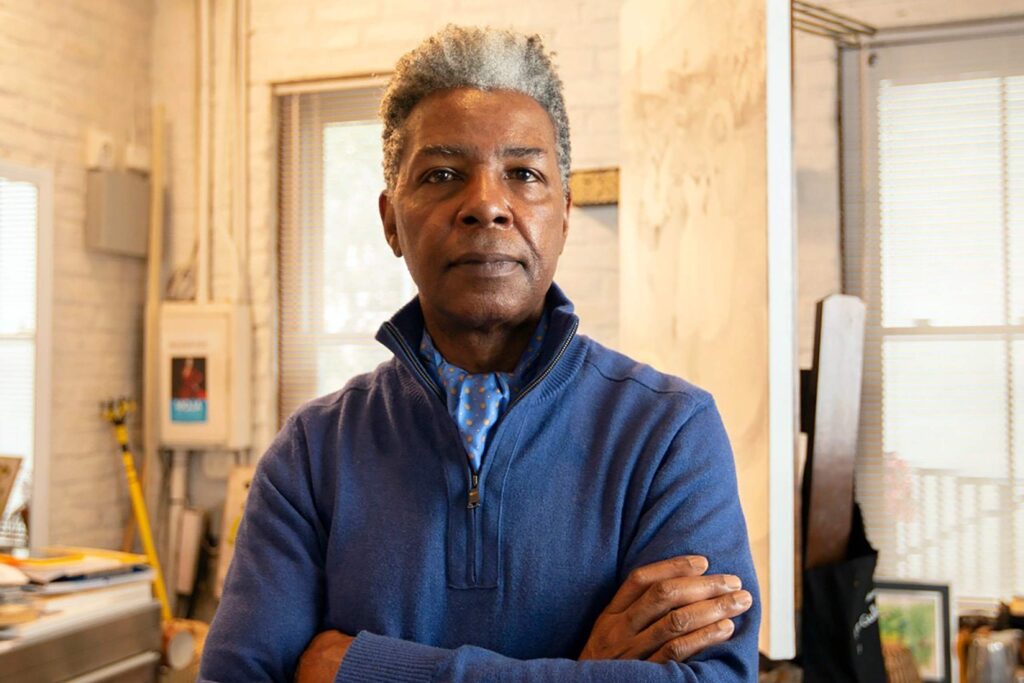

Internationally celebrated painter and cultural ambassador for Charleston, South Carolina, Jonathan Green flew to London to speak on stage at Icons of Inclusion 2025 about the Gullah community that raised him and shaped his work. Talking to OutThere afterwards, the artist shares some idiosyncratic thoughts on reclamation, sexuality and belonging.

In conversation, it’s hard at first to know just what to make of Jonathan Green. Poised, elegant, and oozing demure Southern gentility, the American artist is effusive about the Icons of Inclusion presentation he has just seen by adventurer and keynote speaker Holly Budge about South Africa’s Black Mambas, the world’s first all-female anti-poaching unit. “Their strength is unbelievable. It shows when women can come together, how valuable they can be. I always say to girlfriends and associates – kind of crude, I know, but it’s a reality point – ‘give up the dick. Stick with your girlfriends, regardless. Men will always move around’”.

Not unlike the paintings that have made him widely considered one of the most important contemporary painters of the Southern US experience, Jonathan’s pronouncements can at first glance seem simplistic, even ingenuous, and strikingly at odds with preconceptions it’s hard not to have about his life experience as a gay, African American man making his way in the mid-20th century.

Set in pastoral scenes that evoke his upbringing in Gardens Corner, a small town close to Charleston, South Carolina, his voluptuously colourful canvases initially seem simple depictions of statuesque and richly dressed black women and men going about their daily lives. These paintings, of which Jonathan has produced some 1700 since his 1982 graduation from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, have seen him exhibited and collected in museums all over the world, and have also been incorporated into prestigious dance, opera and theatre productions as well as works of literature. Among a raft of awards and accolades, he was made a fellow of London’s Royal Society of the Arts in 2022, joining the ranks of Karl Marx, Marie Curie, Theodore Roosevelt and David Attenborough. Most recently, the University of South Carolina Beaufort has announced plans to build a new museum, the Jonathan Green Maritime Cultural Center, in his honour.

Romantic, even folkish, Jonathan’s works unapologetically eulogise beauty, harmony with nature, community and a deep sense of belonging against the backdrop of rural life in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, heartland of the US’ Gullah community. “I’m a storyteller artist. My mentors are Jacob Lawrence and Elizabeth Catlett”, he says, bringing into sharp focus the difference between his work and the overtly politicised commentary on the struggles and injustices of 20th-century assimilation in much of those pioneering African American painters’ work. “I can tell many stories”, he continues, “and I have focused mainly on the stories of my community of Gardens Corner, South Carolina, right outside of Charleston”. Living away from home as a young man, first in the United States Air Force, and then studying in Chicago, he came to understand his people’s culture from a different perspective. “I began to see them differently – as a people with a strong link, probably the strongest link with Africa of any of the black American people”, he says.

So familiar through TV and cinema is so much of US culture that it’s sometimes surprising to be reminded how distinct and singular many of the subcultures that are part of it are. Spun from adapted traditions from its people’s various West and Central African ancestries after they were brought, enslaved, to this part of the world to work colonial plantations, Gullah culture has until recently remained unusually undiluted and autonomous, with its own Creole language, crafts, cuisine and spiritual traditions. This is widely attributed to the relative isolation of the South Carolina Lowcountry, a ravishingly beautiful coastal region, largely distributed across many of the Sea Islands, a 480km-long chain of barrier islands consisting of wide salt marshes and sweeping golden sands that stretches from North Carolina to Florida. It was in the heart of this community that Jonathan was born and spent most of his childhood, whose happiness and security shine through the vitality, strength, purpose and dignity of his painted subjects and the sun-soaked, lushly fertile landscapes they inhabit.

And while cultural debates rightly continue about the brutal circumstances of the Gullahs’ arrival in America and ongoing social inequalities there and across the country, Jonathan’s radicalism is to pull focus for a moment to also celebrate the humanity, resilience and loving community spirit of his ancestors, and memorialise the essential role they played in making a thriving economic powerhouse of the region. Dressed in finery, the figures he depicts radiate pride, purpose, dignity and joy. “What if African people came here like everyone else,” asked the official synopsis of Jonathan’s 2015 exhibition Rice in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina – “unchained, unenslaved”? It was after all their ancestral agricultural expertise that established plantations that made rice the area’s prime commodity, their crabbing and fishing skills that created rich local culinary traditions for which the area is still famous. It was even their African-inspired building innovations that gave rise to the collonaded verandas and ornamental metalwork now seen as exquisite signatures of Southern US architecture. “None of it would be here if not for the contributions of my African ancestors”, Jonathan says. “I have so much to be proud of”.

If Jonathan’s subjects seem to embody Gandhi’s much paraphrased exhortation to ‘be the change you wish to see in the world’, the artist himself seems to do the same in how he navigates the world as a gay man. Refusing to label himself, he states that he has never felt anything other than “natural”, an experience he acknowledges has much to do with being “fortunate enough to have been raised by a village”, primarily in his case by his grandmother and her peers.

“These situations”, he says, of queer people who find themselves less integrated and accepted, “arise mostly from lack of understanding, a lack of reading. Nothing is happening now that wasn’t happening before. There was never a time when we, the gay community, were not in existence. So we need to reinforce that we are natural people and should be treated as natural people. Whatever happens in terms of your bedroom activities has no bearing on who you are as a person, on your culture, on your achievements, on what you can contribute to your family and community. So why focus on these labels?”

And then, that slightly eyebrow-raising take on gender roles again. “We need to reinforce this, especially to women. The beauty of the journey, for me, is in recognising that your existence is based on having a firm foundation as a child, and the belief system that you are natural, and that women are truly your protectors as children. They are the innovators, they make things happen, just like those women fighting poaching in Africa. Good mothering, then, is the key”.

In Charleston, where Jonathan lives and works today, and which made him an ambassador for the arts in 2017, an emotionally charged debate continues to evolve over how best to represent its complex history and respect both the harrowing tragedies and cultural contributions of its African American people. Great efforts have been made to truthfully integrate black narratives into the rich cultural life of this charming historic city, which, known for its picturesque colonial architecture, distinctive Lowcountry cuisine and genteel Southern manner, attracts some 7.4 million visitors a year. And while many changes bear witness to sincere reparation intent – for example plantation tours themed around the experiences of enslaved people, the symbolic removal in 2020 of a prominent statue of the vocally pro-slavery former U.S. vice-president John C. Calhoun and the impressive, new-in-2023 International African American Museum, where Jonathan’s joyous 2005 painting Beach Dance hangs among sobering exhibits illuminating the horrific realities of slavery – the rising cost of living driven by Charleston’s tourism success have seen half of its black population leave for cheaper communities over the last 40 years. A hundred and twenty buildings damaged in BLM-triggered unrest in 2020, meanwhile, revealed the distance still to go before many black residents feel equitably treated.

At 70, Jonathan’s far from done playing his part. A dynamic online museum resource since 2024, the Jonathan Green Maritime Cultural Center’s soon-to-open bricks-and-mortar incarnation will bring the region another beacon of diasporic pride, illuminating its illustrious history as a hub of maritime trade and the essential and little-known contributions of its African American workers. “My business partner in this, Dr. Kim Long, and I are very interested in helping educate people to understand the importance of Africa”, he explains, “and, using port cities as the conduit, to show how Africa has transformed the world”.

www.jonathangreenstudios.com | www.charlestoncvb.com | www.jgmcc.org

Photography by Joel Ryder, courtesy of Jonathan Green and Explore Charleston, artworks by Jonathan Green