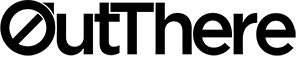

Wellness tourism is worth $850 billion worldwide. Where holidays were once about indulgence, they’re increasingly an attempt to hack our health and cheat death, as Zack Cahill explores.

Every now and then, a picture makes the rounds of the beloved 1980s sitcom Cheers. The cast is in their prime — Ted Danson’s rakish Sam Malone, Nicholas Colasanto’s kindly Coach — and next to their faces are their ages. They’re shockingly young.

It’s a common question online: why do people in the past look so old? I’ve often measured my own age against Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon, grumbling about being “too old for this shit”. He was forty in the first film, playing fifty, but not aged up with makeup. I am now two years older than Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon. Two years beyond “too old”.

Even family photos can provoke this Nabokovian crisis — your father at twenty-three, ruddy and moustachioed, forearms like Popeye, holding the infant you. A man already.

People in the past really did look older. They smoked more, drank more, and viewed SPF 50 as a conspiracy by Big Sun. Compare those weathered faces to a near-sixty-year-old Keanu Reeves or a fifty-four-year-old Paul Rudd (Reeves is now almost the same age as Estelle Getty in The Golden Girls).

Some of this is selection bias. Some is the severe styling of the past versus today’s youth-obsessed aesthetic. But sunscreen, gym culture, and better diets are undeniable factors. I’m old enough to remember being driven around by friends’ parents, windows sealed, both of them chain-smoking like stressed Frenchmen. When I first started going to the gym, I didn’t tell my parents and hid primitive, chalk-flavoured protein powder under my bed like pornography.

Believe it or not, even in the nineties, being “into health” carried the vague whiff of perversion. Suggesting something as depraved as a “wellness holiday” was unthinkable. And yet here we are in 2025: the health-and-longevity retreat is booming.

Global wellness tourism was valued at around $850 billion in 2021, and it’s projected to reach $2.1 trillion by 2030. And they – these well-heeled seekers of moist skin – spend 35% more than the average traveller. The wellness sector has seen a larger post-COVID bounce-back than other niches within the travel industry.

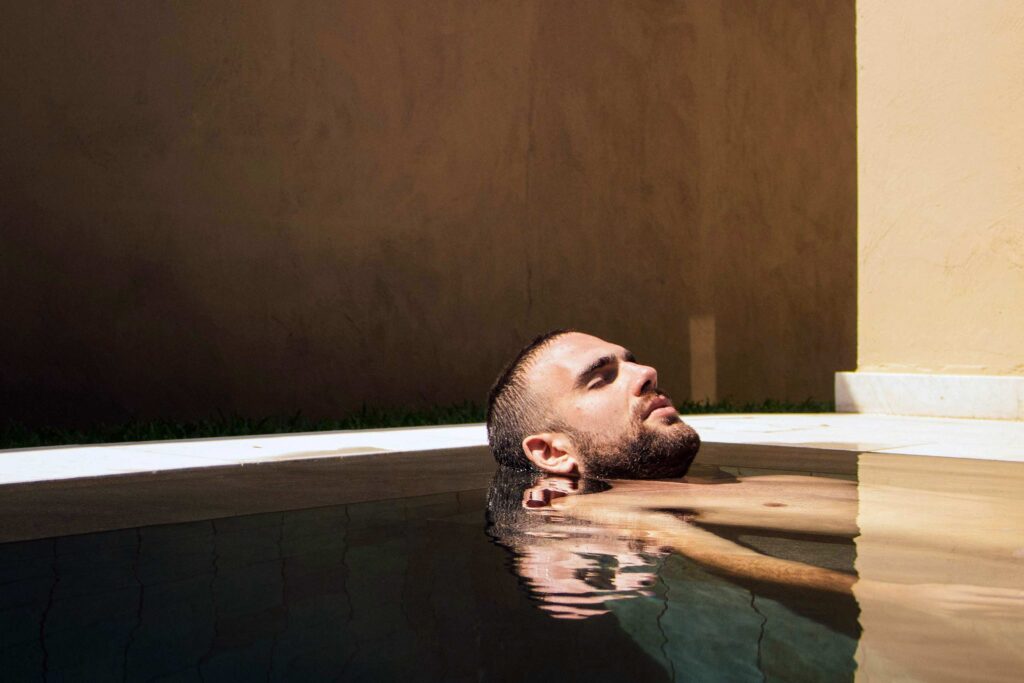

Health retreats have been around forever; think of 19th-century health spas and the like, consumptive romantic poets being sent off to take the mountain air. But this is different. These modern wellness tourism destinations aren’t simple, rustic cabins where you drink carrot juice and do yoga. The kind of fitness currently en vogue is firmly a product of the podcast era. We’re talking red light therapy, stem cells, and the ubiquitous ice baths. Quantified and tech-forward and verging on sci-fi. Bond-villain lairs for biohackers.

Maui’s Four Seasons offers a $44k treatment suite including ozone therapy and stem cell infusions. In Utah’s Amangiri, tech billionaires plunge into ice baths between guided desert hikes. A ten-day stay will cost as much as the average US salary.

Where did this all come from? In one sense, it’s nothing new — rich people have always paid to be told to drink water. But today’s retreats are turbocharged by two forces: money and metrics. After 2008, wealth clustered at the top, and the top got anxious about mortality. At the same time, the Fitbit-and-podcast era gave us endless data points to optimise. If you can track your REM sleep to two decimal places, surely you can buy yourself twenty extra years.

Add all that to the bonfire of Instagram and TikTok, where we rate our faces and bodies against people whose job it is to look good, and they still cheat with filters, fillers, and steroids. It’s wealth plus tech plus status anxiety, multiplied by Joe Rogan.

But it’s deeper still. The Western world has been experiencing a severe meaning gap. The more religion has fallen out of favour, the more health obsession has poured in to fill the cracks. In the absence of God, we’ve turned to vitamin D and wearable tech. Instead of confessing our sins, we log them in an app. We hone our morning routines for optimum wellness. The rituals are different, but the faith is just as fervent and twice as annoying. Youth and beauty are the altars we worship at, and the eternal life we seek is literal.

It reminds me of a Woody Allen quote: “I don’t want to live on through my work. I want to live on in my apartment”.

But the sad truth is, no matter how rich you get, no matter how infinitesimally you measure your sleep and stress, no matter how many ice baths or vitamin IVs you take, you’re eventually going to die.

And when you do, people will most likely look at your corpse and say: “Wow, he was younger than Paul Rudd?”

Illustration by Martin Perry, photography via Unsplash