It was a trip so anticipated, a time to experience Catalan art in its natural setting. Yet, Steffen Michels is soon unsettled by Antoni Gaudí’s works in Barcelona, until a chance encounter makes the scales fall from his eyes.

When the Modernist wave seized Europe at the turn of the 20th century, not even the mighty Pyrenees could stop it from sweeping over the Iberian Peninsula. But nowhere did it prove more popular than in Barcelona. Here, the movement gained enough sway, confidence and individuality to become a thing in its own right. Modernisme was Catalonia’s equivalent to the French Art Nouveau and the German Jugendstil, but its echoing of early voices calling for the region’s independence from the rest of Spain gave it a distinct quality – so did Gaudí, arguably the movement’s most acclaimed artist.

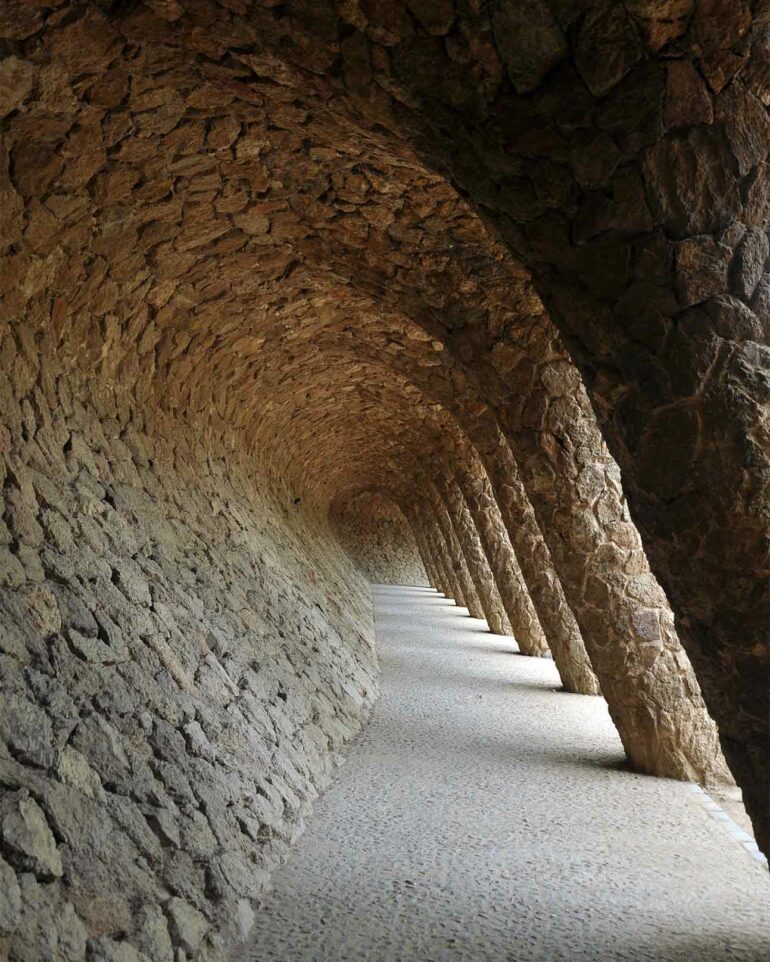

Like that of his peers, Gaudí’s work appealed to people on an emotive level. It advocated a more bohemian world view and claimed a seat at the table of the cultural sphere for an outspokenly Catalan art and way of life. In Barcelona, the region’s capital, this way of life found its most prominent expressions. It was here that the Park Güell, originally planned as an upscale housing development by Spanish industrialist Eusebi Güell, opened to the public in 1926. The park features all the hallmarks of Gaudí’s genius: organic architecture, originality in shape, complexity in detail and – somewhat bizarrely – a larger-than-life lizard sculpture, which at the time of my visit is hypnotising a nearby gaggle of Instagrammers to take a selfie in front of it.

Entering the gardens, I feel like a six-year-old walking into Disneyland for the first time. And then, a good thirty minutes into my visit, the feeling starts to fade. If ever you’ve gone on a blind date and things didn’t quite work out as expected, you’ll know what I’m feeling. The longer I explore, the less joy it sparks, and the more unsettled my inner Marie Kondo seems to get. What had struck me as grand at first, struggles to inspire me at second glance. Sure, the trencadís mosaics of the main terrace are beautifully executed (so much so, in fact, that the invention of the trencadís technique is often falsely credited to Gaudí) but, in my opinion, they also look a tad old fashioned. That’s the thing with any break from more timeless aesthetics, of course: it comes with an expiry date.

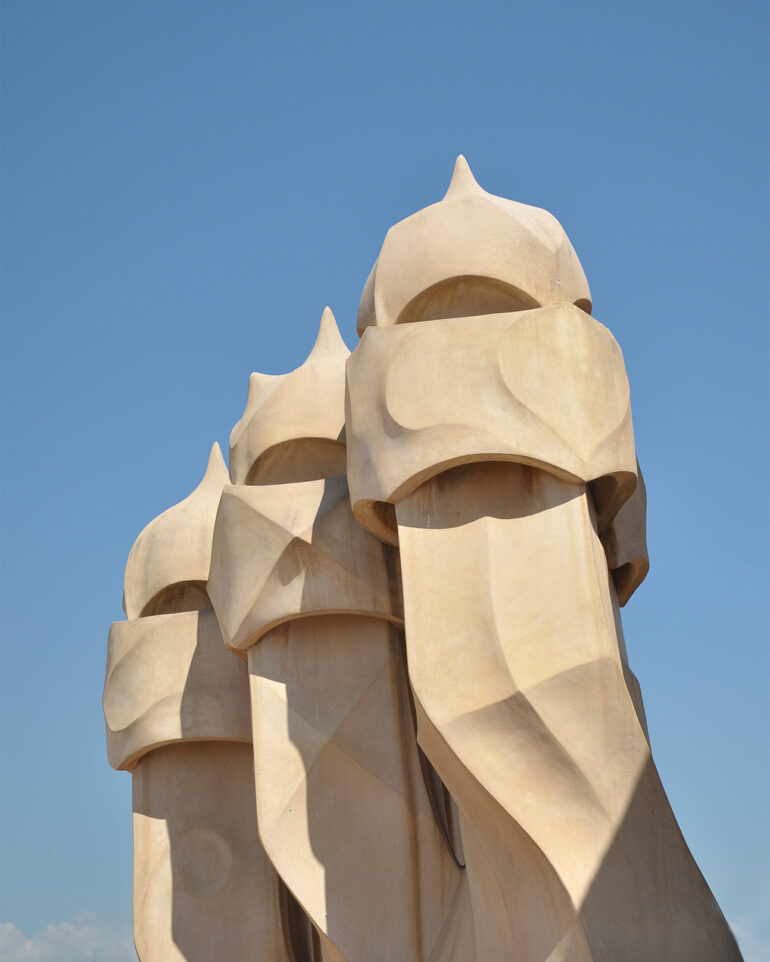

But has my love affair with Catalan art passed its sell-by date as well? Perhaps we’d been long-distance for so long, our coming face to face in the movement’s homeland was bound to be awkward. I’d marvelled at the imagination of Catalonia’s artists in museums from Munich to Amsterdam and Gaudí’s edifices had always struck me as awe-inspiring in pictures. Nonetheless, the Park Güell leaves me underwhelmed. Ensuing visits to the orientally ornamented Palau Güell and the Casa Milà fail to reignite the flame in my heart. Don’t get me wrong: both will be fascinating to any dilettante. The latter’s chimneys even inspired Star Wars creator George Lucas in the iconic design of the stormtroopers’ masks – but futuristic and alien as they may be, their effect on me is short-lived. And so after yet another failed attempt to connect with an art form whose merit is beyond discussion, I call for a break. It’s not you, Gaudí. It’s me.

That’s when I bump into Anna, a bubbly local whose eyes meet mine as we wait to order drinks at a rooftop bar in the city’s Eixample district, commonly known as the ‘Gayxample’ among LGBTQ+ folk. Anna turns out to be the kind of person who has a million stories to tell and not one filter to put them through. She’s very animated and very Catalan, though they’re really just two different words describing one and the same idea. Within minutes of befriending her, I know the most intimate details about her 60-something years on this planet (it’s not that I ask, I’m just not given a choice).

“When I young, I very active with the men. I take what come at me,” she blunders in an exuberant Catalan brogue. “Marry when 23. He have so much money. We move London. I don’t work. My job is waste money like water – Harrold, Selfridge, Howie Nicholl.”

As she finishes, we both pause for a minute. A salty breeze wafts across the open-air space as Café del Mar-like tunes ooze from the speakers and a young gay couple reclining on poolside loungers clink glasses. Taking a sip from a G&T that seems more G than T, I finally say, “sounds like love”.

“Oh, no love. Just stupid. We divorce after three year and I move San Francisco. Lots of fun, this city. I seduce many men there. Don’t care you have girlfriend. I just want to borrow. One night only,” Anna explains with the casualness of a tech CEO acknowledging data breaches in court.

“I was troublemaker and I love. In Spain, is also easy seduce someone. I go to men in disco, slowly, and look in the eye. Then I say ‘tienes mucho por avante’. It mean ‘you have a lot ahead of you’. Work every time.”

It’s an ice-breaker, that, and so when Anna asks how I’m enjoying Barcelona, I tell her the truth, “I just don’t seem to get Gaudí. The Bellesguard is so Gothic and the Casa Vicens so busy to look at. His buildings are interesting, but the man himself is completely elusive.”

Anna gasps, eyes wide open.

“You silly. No one tell you? To see soul of Gaudí, don’t look what he make. Look what he love!”

Journey to Sant Jeroni

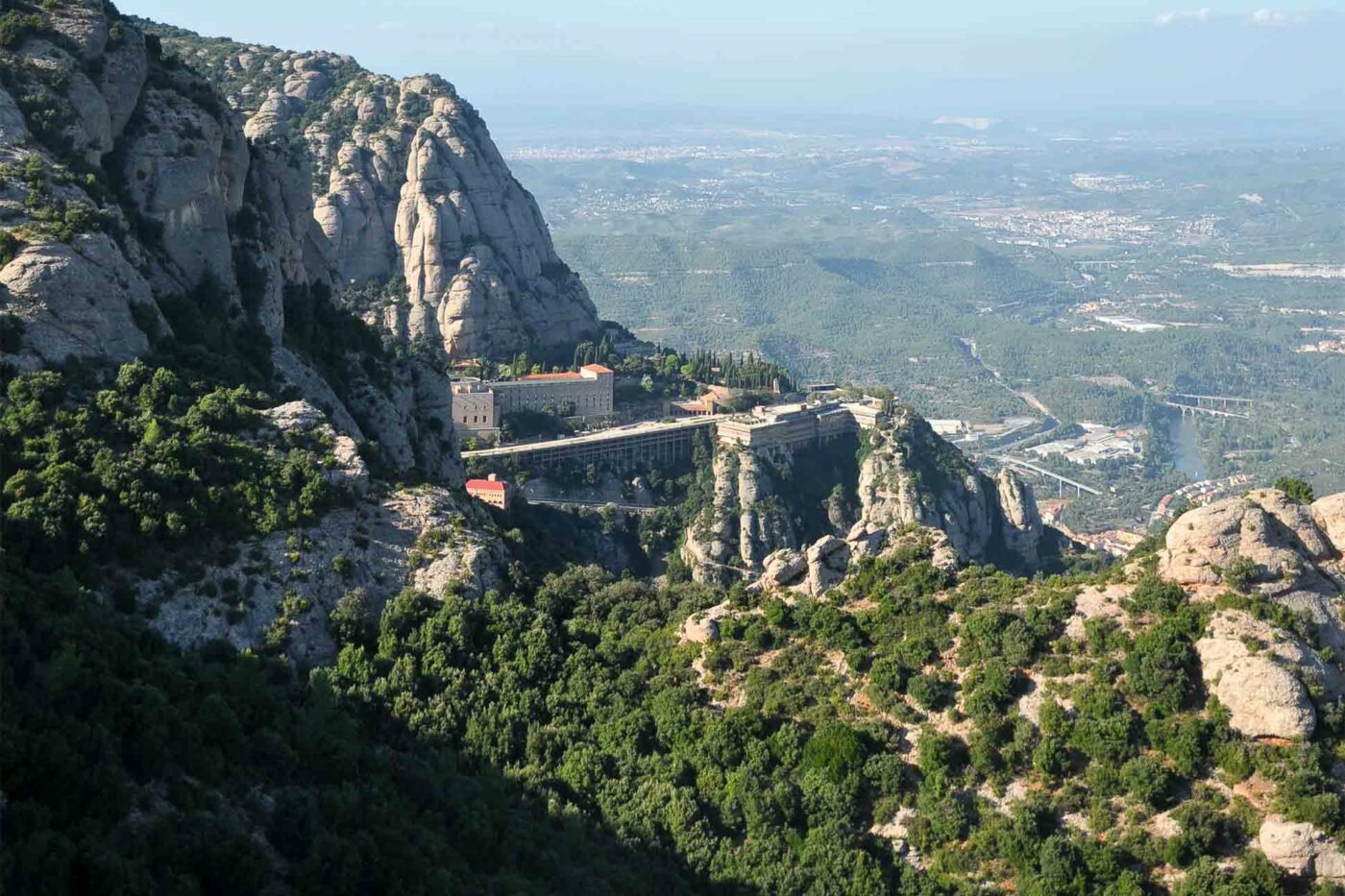

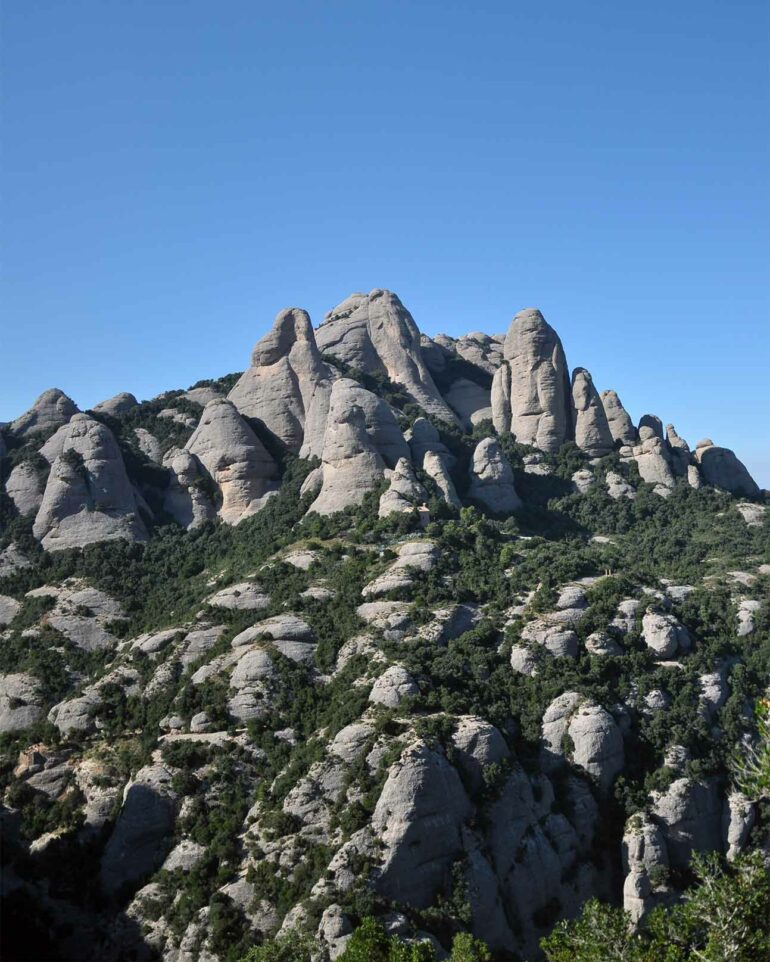

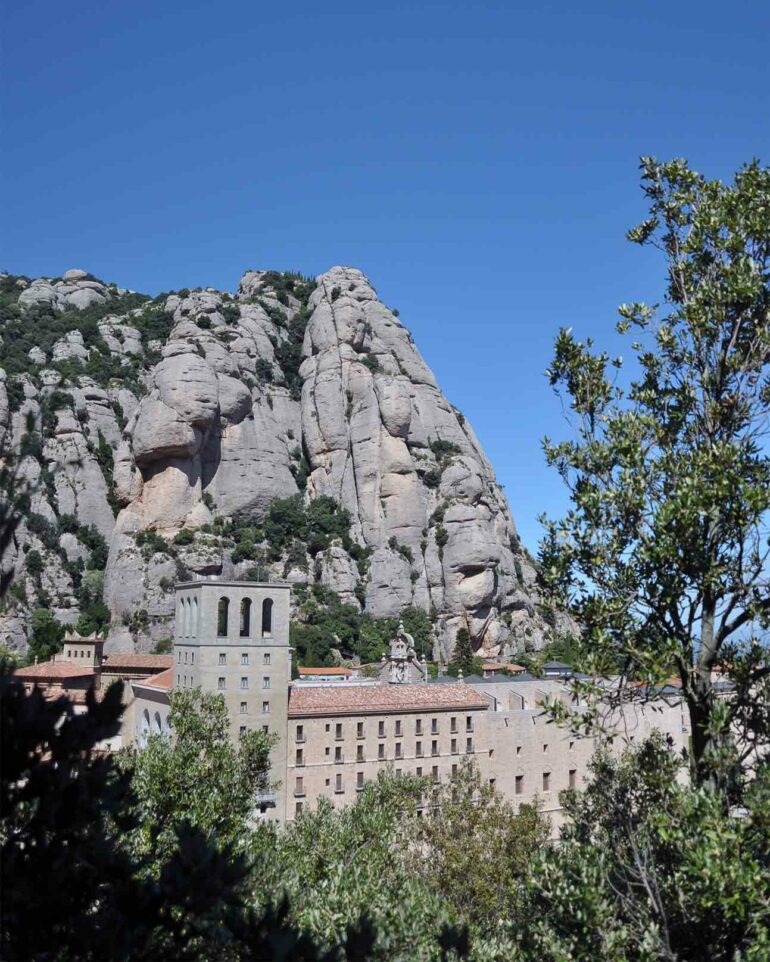

What Gaudí loved during his day was religion and nature. At the 11th-century Santa Maria de Montserrat Abbey, an hour outside Barcelona, I find both. It’s a vast complex, built into the rocks of Sant Jeroni mountain. The structure itself is imposing and houses a rare Black Madonna, but it’s the surrounds that steal the show: picture a micro mountain range made up entirely of rounded boulders seemingly stacked up against one another, a bit like a real-life version of a Super Mario World backdrop from the early 1990s. Lively-looking trees spring out of crevices, warm light bounces off smooth, camel-coloured rock and the muddy River Llobregat caresses the foot of the mountain, looking much like a mini Mekong. It’s the perfect place to leave your worries behind and, in any case, lugging mine up 1,236m isn’t a prospect I can reconcile with being on vacation.

Perhaps it’s the religious theme, but the hike from the abbey to the top of Sant Jeroni feels a bit like a pilgrimage. With every metre I climb, the air in my lungs seems to be getting crisper and the rock beneath my feet more solid. And the very way I experience the setting changes, too: from below, a mountain seems grand, crushing and utterly external. But ascending it, the body constantly grapples with the sheer force of its size and, in some strange way, it almost becomes one with it. Of course, I’m not the first person to feel this way. The idea of a corporeal intelligence – a body that can sense its surroundings – has filled volumes of philosophy books.

It’s something we all feel in infancy, on a non-articulate level, long before the confines of language rationalise our experience of the world around us. As adults, having traded our instincts for reason, we only tend to feel our surroundings in extreme, natural environments. Such places have an immediacy that confronts us with our physical awareness of the landscape: if ever you hiked through the thicket of a rainforest or scuba-dived in open waters, you’ll know what I mean.

What’s so precious about this experience is that it reminds us of an indescribability to natural phenomena that’s perhaps the very essence of their purity. No words can truly capture the monumentality of a mountain or the feeling of standing on a beach when the tide rolls in and submerges your feet in a body of water so vast it’s home to both icebergs and coral reefs, tens of thousands of kilometres apart. In those moments, we experience nature not as a grand other, but as something absolute, inherently within ourselves. It’s an experience neither purely physical nor merely concerning the mind and the only appropriate reaction to it is to pause and feel in silence as we look out into the world and find our very selves staring back.

Standing on Sant Jeroni’s summit, with the sun hanging in the sky like a lantern on fire, I do a lot of looking. The panorama stretching out all around me is easy to get lost in. So easy, in fact, not even a Ukrainian backpacker with an obnoxiously loud phone manages to distract me as he tries to show me a YouTube video of his favourite eastern European pop star (thankfully, there’s no signal at this height). From up here, I notice the subtleties of the surrounding Catalan countryside for the first time. They make it distinguishable from other Spanish landscapes: there are wave-like elevations running all across the land, rock formations that have been smoothed down by millennia of rain coming in from the Mediterranean and the very atmosphere itself is like a hazy veil hovering patiently above the sea. It makes for a perfectly distinctive landscape – one in which Gaudí’s impetuous pursuit of the grand, ethereal and pure seems reflected back at me. And one so full of spirit, you’d be tempted to think the things the artist ‘loved the most’, religion and nature, are indeed intrinsically intertwined. This, I think, must be Gaudí’s soul and, just perhaps, the underpinnings of Catalan culture.

As I make my way down, a visibly exhausted hiker stops me mid-trail.

“Are the views worth it?” he pants. I look at him and smile.

“Tienes mucho por avante.”

A forest in stone

It was only in 2019, 137 years into its construction, that a building permit was granted for Gaudí’s unfinished masterpiece, the Basílica de la Sagrada Família. A sacred site for architecture aficionados and a thorn in the eye of Catalan bureaucracy at equal parts, the Sagrada is impossible not to be amazed by. As my gaze scales its facade, I can’t help but notice the way in which it evokes the spirit of the Catalan landscape I saw from Sant Jeroni: the reiteration of spires not unlike the mountain’s boulders piled upon each other, its reliance on golden-hued and sun-beaten sandstone and a wealth of detail that keeps the eye wandering. Though that’s nothing compared to the spectacle that awaits on the inside.

They say Gaudí wanted the Sagrada Família to be a ‘bible in stone’, but I find it’s a forest too. Tree-like columns shoot from the ground, splitting into a canopy of branches that hold the sun and the stars in the sky above. They sparkle from a foliage of a thousand tiny recesses, filling the upper realms of the basilica’s atrium with a glow so dense, it seems almost tangible. Standing in the nave, I notice the stained-glass windows facing east – they feature pale, cooler colours reminiscent of a chilly morning – and those to the west – dominated by fiery reds and bright yellows that burn with the arrival of the late-afternoon sun. There are sinewy elements, structures that remind me of bones and a crypt that feels positively womb-like. In short, the Sagrada is incredibly organic. And, just like nature, Gaudí’s biggest inspiration, it holds something wild, eluding even the fanciest of adjectives. In this respect, the basilica isn’t a mere translation of Catalan landscapes. It speaks of their ability to appeal to one’s senses. As I look up towards the main opening above the apse, I imagine the old man winking at me from above, a cunning smile on his face.

Whether Gaudí ever stood atop Sant Jeroni, envisioning the Sagrada, I’ll never know for sure. What’s more important, however, is that he gave physical manifestations to Catalonia’s way of life, making a case for its right to exist independently by depicting its idiosyncrasies. He was opposed to the region’s culture being absorbed into a general Spanish value system, with its more bourgeois overtones. In contrast, the Catalan heart leans towards the more chaotic, lavish and sometimes bombastic – Anna had certainly been all three of those things. But it’s also anchored in the pure and divine, from celebrating nature to savouring life’s simple pleasures. Catalonians eat well, drink better and have few inhibitions about sex. The unique physicality of Gaudí’s works speaks of their joy, and of what’s to be expected from a trip to Barcelona.

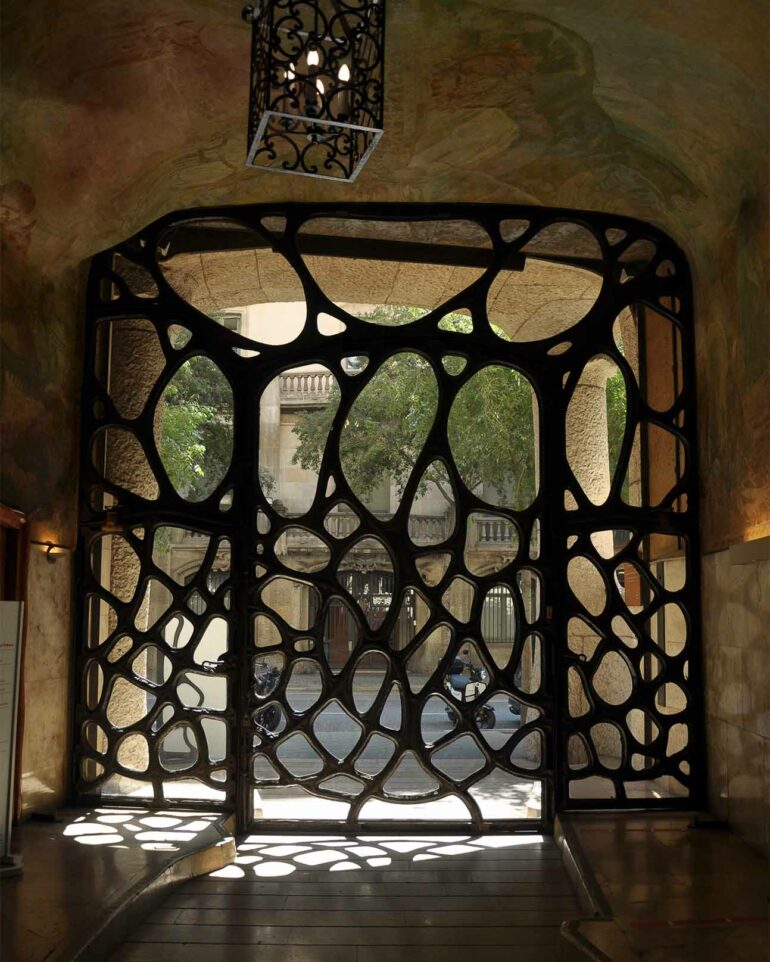

Before the architect’s life was tragically cut short by a passing tram in 1926, he’d applied the Modernist mindset to a level far below the surface. More than his contemporaries, Gaudí wasn’t merely concerned with aesthetics, but with the very nature of things as such. His striking edifices and grand ideas, from the Colònia Güell to the Casa Batlló, are love letters to the Catalan spirit. And their foundation, quite literally, remains deep within the region’s soil. It can take you a while to understand this, but once you do, the city stretches out in front of you like one gigantic playground waiting to be explored.

For more about Barcelona and its neighbouring attractions, visit www.catalunya.com.

Photography by Steffen Michels

Get out there

Do…

… go on a Joan Miró trail, starting with the Fundacio Miró and ending, somewhat fittingly, with the painter’s final resting place in Montjuïc Cemetery, a Barcelona attraction in its own right.

… make time for walks. The Olympic complex is a sight to behold and the Mirador del Migdia hiking trail offers gorgeous, coastal panoramas.

… swing by the scandalously underrated Monastery of Pedralbes, one of the finest Gothic buildings in Barcelona. Keep an eye out for the cute cat flaps in the nuns’ laundry room.

Don’t…

… bother making the 20-mile trip to Sitges on a grey day – the beaches and seafront promenades at this LGBTQ+ hotspot will be deserted. Save the treat for when the sun and the crowd are out.

… weigh in on the Catalan independence movement unless you know what you’re talking about. Opinions are divided and you could end up offending someone.

… visit if the idea of pretty town squares where delicious tapas are served and cava flows liberally scares you. You would be terrified of Barcelona.

The inside track

Yolanda Muelas is editor-in-chief of Metal magazine, a bi-annual arts and fashion title based in Barcelona and known for its cutting-edge visuals, fiercely independent spirit and curious eye.

www.metalmagazine.eu | @metal_magazine

Shop

SVD is one of the best urban fashion stores in Barcelona. Sneakers are their strong suit, with special and limited editions, but you will also find top brands such as Rick Owens and Junya Watanabe.

Savour

The young team behind Teòric offers seasonal and organic tasting menus that introduce guests to traditional Catalan cuisine. They’ve received rave reviews since opening – book in advance.

Browse

Free Time is a veteran Barcelona magazine store. Odd Kiosk specialises in queer culture, and News & Coffee is a fresh take on newsstands, serving (you guessed it) terrific coffee.