Sometimes it’s the places and situations you least expect that surprise and delight you. In a rural idyll in the state of Brandenburg, just over an hour from Berlin by train, a beautiful guesthouse and garden manage to do just that – and not just for those who come to stay at Hof Flieth, but for its OutThere owners as well.

Less than two hours ago, I boarded a train at Gesundbrunnen station in inner-city Berlin. Now, I’m floating on my back in a lake, staring up at the clear blue sky. Nature abounds here: colourful wild flowers and lush green grasses basking in the sunshine. A large dragonfly hovers above me, glorious birdsong fills the air. I can hear the joyful laughter of young families splashing around near the shore.

It’s hard to imagine a better welcome to the Uckermark region than this. It’s early July and the very definition of a perfect German summer. No wonder then that for the next three days, I spend barely any time indoors, taking all my meals outside, going for long walks and visiting some of the many lakes that lie within easy reach of Hof Flieth, the rural home of my hosts Andreas (Dre) Zaremba and Gary Abela.

I can’t say that I have a great deal of knowledge of the area, but then, neither did Dre and Gary when they first came here back in 2016, almost by accident.

“Our friend had rented a holiday home here,” recalls Gary as we all share a pot of coffee around their farmhouse kitchen table, “and we only intended on visiting her for a night, but we decided to crash the rest of her stay. We had always spent a lot of time with the dogs in the surrounding countryside of Berlin, but we had never ventured up north.”

Gary talks enthusiastically – and quickly – his North London accent still unaffected by his years in Germany. His handsome, friendly face, which often breaks into a broad, cheeky smile, is framed by long black hair that matches his cavalier moustache and beard. He has what my grandmother would have described as a ‘twinkle in his eye’, and I can’t help but be drawn in by his charm and ardour.

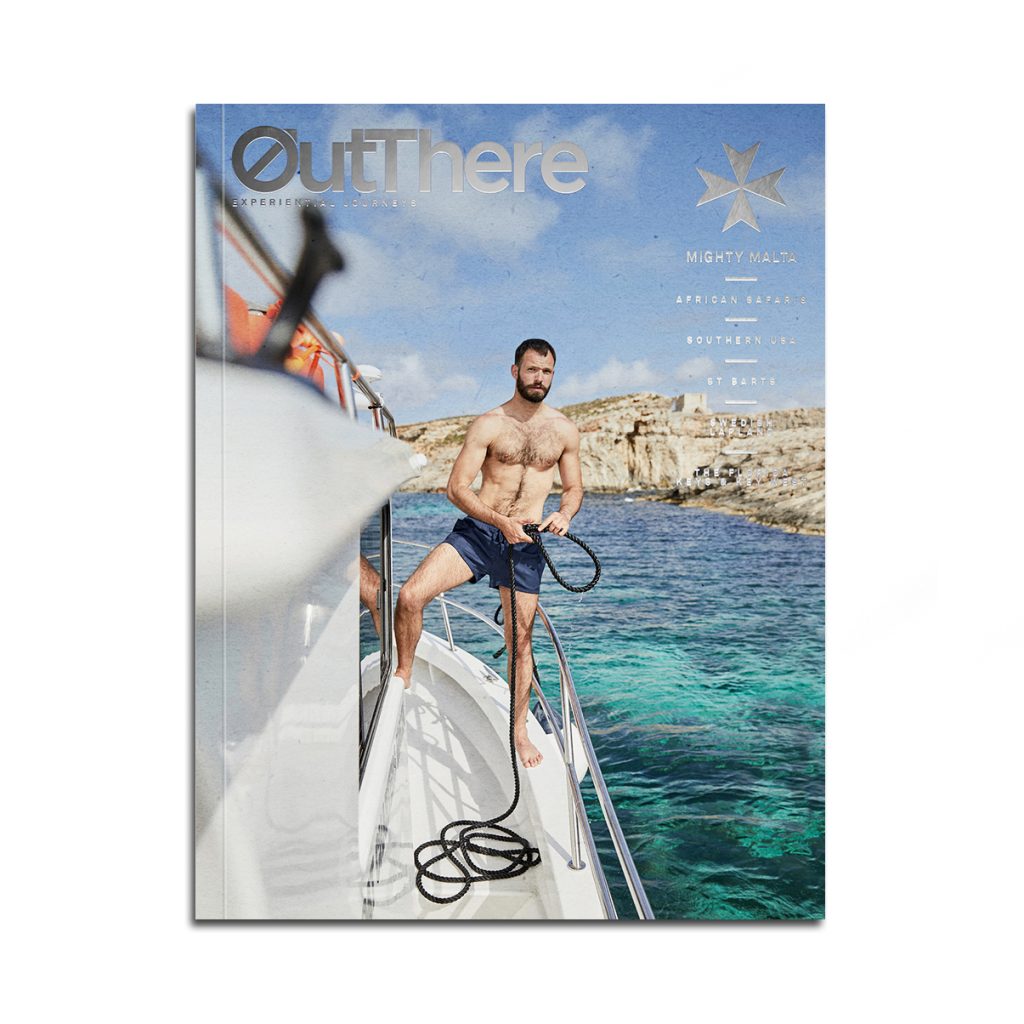

Gary’s parents emigrated from Malta to the UK in the 1970s and bought a hotel, where Gary grew up and worked whenever needed. Hosting – and hospitality – are therefore second nature to him. Within minutes of meeting him, he makes me feel like an old friend and, throughout my stay, he was attentive without ever being at all invasive.

“We fell in love with the lakes, the glacial hills, the cultural offering and, most of all, the proximity to Berlin,” he continues. “So a few weeks later, we rented an old Volkswagen camper van to explore the area and take a little holiday with our dogs, all while doing some property viewings.”

This story first appeared in The Mighty Malta Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

At the time, the idea was to look for an investment place that they could rent out. Dre and Gary were already part of a host-economy, so a new countryside property would accompany and complement their portfolio of guest apartments in Berlin. The added benefit was that they could have somewhere to escape the city from time to time, whenever the house wasn’t let. Little did they know just how much it would cause them to re-evaluate almost every aspect of their busy, city-focused lives.

Their search for the perfect property took about two years. Then, the COVID pandemic hit, which forced them to spend more time out here than they’d expected. It was then that they truly realised their passion – accompanied by brimming energy and creativity – for transforming the property. They threw themselves into a life that they didn’t know before, one that profoundly changed their outlook.

“Ironically, I didn’t like the house at all at first,” admits Gary. “But Dre immediately saw its potential. We had done flat renovations before, but never a large house. I just couldn’t get past the dull brown roof and outdated windows. But, what did sell it to me was all the land [the house came with a hectare of it] and the countryside views. Not that I had a clue how to work the land, having been raised in central London. But Dre loved the idea of landscaping a garden from scratch. And the village was nice and had some infrastructure, including a small deli and pub. Plus, there is also a train station nearby that connects the village directly to Berlin.”

The old house also had a separate apartment, which would make a perfect holiday rental, so that was another bonus. It’s clear that Dre and Gary’s commercial savviness wasn’t clouded by this passion project.

“Then, of course, there is the proximity to the lakes, which is a big plus,” adds Gary. I nod in agreement – I got to enjoy one of them for myself that afternoon. “We are in the middle of what is probably one of the most beautiful parts of Uckermark. But it was really the cultural side to the area that swayed us. We liked the fact that it was somewhat more colourful than in most countryside places around Berlin. Many artists and other former city-dwellers had moved here some 15 years ago, paving the way for others to follow. This meant that there was already an acceptance of outsiders and just different people in general, like two gay men. It meant integration would be easier and also meant there would be more happening culturally, more things for us and our guests to do.”

The region reminds me of upstate New York. Uckermark’s close proximity to the city and a reliable train service (and typically good German roads), combined with its outstanding natural beauty and relatively cheap property prices, have lured successful, sophisticated Berliners seeking a rural refuge. Just as in places such as Beacon, Hudson and Woodstock, the influx of middle-class sophisticates has brought with it the trappings of city-ish life. I had braced myself for the fact that spending a few days in the German countryside would mean leaving behind certain luxuries, but I was wrong. The village shop – as just one example – is, in fact, a very upmarket deli, selling organic produce and frighteningly expensive coffee.

Gary and Dre took me to their favourite place to eat – Gaia Feed, a rustic restaurant set in a community garden called Grosser Garten. There, we were served with plate after plate of delicious, beautifully presented, organic food by a young English waiter. The restaurant was just coming to the end of its two-year ‘residency’, as the owner of the garden likes to keep things fresh. So, the future will see something new, yet equally exciting.

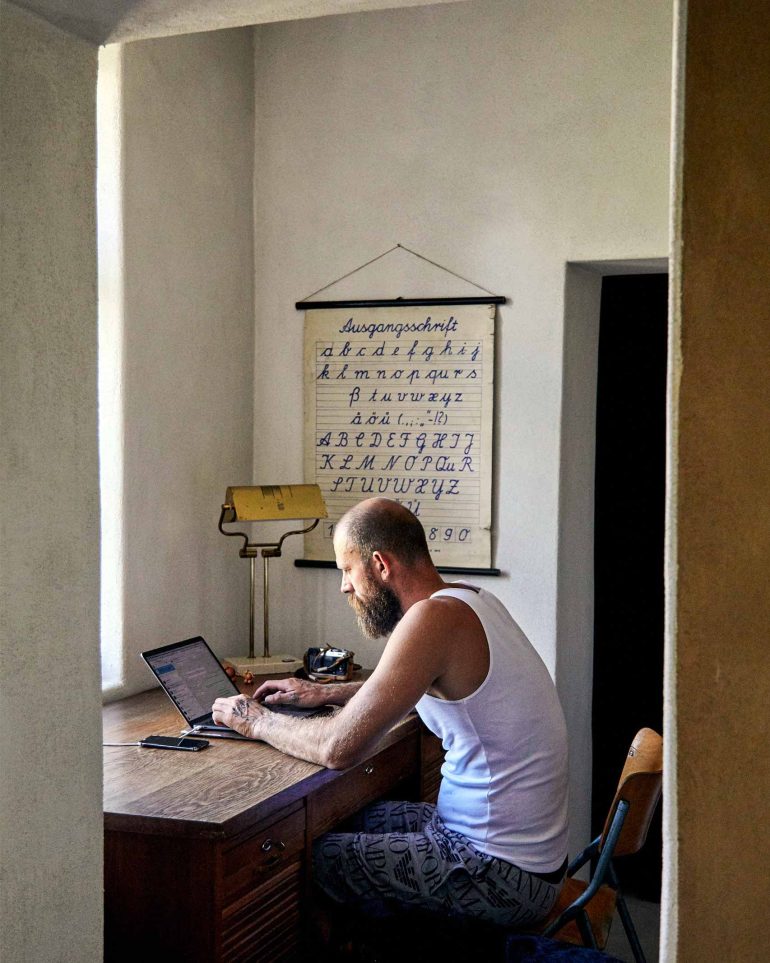

“We haven’t really touched the outside of the house,” the softly spoken Dre tells me as he digs around in a kitchen drawer, coming back to the table with a large handful of photographs. “We have created an office in one of the old storerooms at the back, but we’ve put a huge amount of effort into the garden.”

Dre is a keen and very talented photographer. It was his photos of their life in the area and of their beloved dogs – Reggie, Nina and Goncho – and the way he has captured the surrounding countryside that really convinced me to pay them a visit. And the photos are proving popular – he shares them extensively online and via social media, where they receive a lot of attention.

“Inside a building, you’re limited by the walls. Whereas in a garden, it’s much more about putting down things in layers, and then you’ve got the whole extra dimension of how everything is going to change over time and with the seasons.”

I first met Dre some 10 years ago on an OutThere photoshoot, when he was modelling for us. He’s a strikingly good-looking man, with a shaved head and a thick beard and, at 6’4”, he has a real physical presence, accentuated by the ‘prison-style’ tattoos that cover his body, somewhat ‘disguising’ his understated and thoughtful intelligence.

Dre was born in 1982 to Polish parents amidst what was a very difficult decade, the lead-up to the fall of the Iron Curtain. Having spent much of his early life in Warsaw, he still remembers elements of living in a communist country. From the age of seven, he went to school in a small town in southern Germany. He was raised there until he went across the pond to Oklahoma, where he attended an American High School for a year until graduation. His degree in International Business Management took him further across the globe. He lived, worked and studied in China and Spain for some time, before eventually ending up in London, where he met Gary.

Dre hands me the photographs, which show their lot’s progression from a large, uninspiring lawn dotted with a few fruit trees and outbuildings, into a muddy building site, and then the various stages of its transformation into its current state, a stunning garden designed with sustainability in mind. But, despite his years of experience renovating apartments, Dre had initially felt a little out of his depth with the garden project.

“I’d never had to work spatially,” he explains. “Inside a building, you’re limited by the walls. Whereas in a garden, it’s much more about putting down things in layers, and then you’ve got the whole extra dimension of how everything is going to change over time and with the seasons. We were sowing seeds and planting tiny seedlings of plants we weren’t familiar with. Rainer Elstermann, our landscape and garden architect, sent us a long list of plants, which we obviously looked up online, but it’s hard to imagine how they’re actually going to look in reality. So, it was a matter of letting go of control a little bit.”

The resulting garden – now into its second summer – is a joy to be in and hits every sense. Approaching the gate for the first time, I was struck by the sound of honeybees busily collecting nectar from the myriad wild flowers. Winding gravel paths lead me through all manner of plants, from grasses to herbs, some of which release their scent as I brush past. In the centre of the garden, the delicate flora is juxtaposed with a Brutalist concrete seating area. A circular, metal fire-pit forms the centrepiece. Beyond are a row of outbuildings, which divide the space into an outdoor kitchen and vegetable garden. Nestled away in a secluded area at the back are a hot tub, outdoor shower and sauna, with views of the land beyond. Around the back of the house lies a small orchard of fruit trees, where we eat most of our meals, lovingly prepared by Gary, who has grown all the fruit and vegetables we enjoy during my stay.

It’s funny to think that over a decade and a half ago, their lives couldn’t have been more different. Dre and Gary met in 2005 on the dancefloor of the legendary North London nightclub The Cross. At the time, Dre was a student in Spain. Afterwards, he moved to London to work for Hugo Boss, while Gary was working a corporate job, heading up a distribution business for an asset-management firm. On a backpacking trip around South America in 2011, they decided to pool their resources and capitalise on the cheap property prices in Berlin. Over time, they ploughed all their savings and income into their portfolio in the city, while choosing to live in a small studio flat in London.

Their ultimate aim was to move to Berlin and have some financial freedom, which they finally achieved in 2015. Things were going well until one day they received a call from a friend who worked at the local police force, informing them that a poster with Dre’s face on it had just landed on her desk. Beneath his picture were the words ‘Who knows this guy? He has two dogs and runs an Airbnb in this neighbourhood. Let’s find out where exactly, break in and squat his apartment’.

Dre wasn’t the only one they targeted: the anti-vacation-rental vigilante group picked on all the Airbnb superhosts in the area. They blew their profile pictures up on to posters and then pasted them around the city. They had recently accessed and squatted in an apartment and the break-in was broadcast live on social media as it happened.

“I don’t really speak the language fluently and the locals don’t speak much English either. But everyone was so lovely, inviting us into their homes for tea and cake.”

“The whole thing was quite scary,” recalls Dre. “Not only was I worried for our own safety, but also for our dogs’, and it also crossed my mind that they might try to burn my place down if they found out where it was. A few days later, some graffiti appeared outside our building, indicating that there was an Airbnb inside somewhere. I notified all our neighbours, as I felt it potentially impacted on them too. It was a personal and uncalled-for attack: unlike 95 per cent of Airbnbs in Berlin, we have a licence that is approved by the city administration.”

Ultimately, the experience made Dre and Gary stronger. It also taught them how to argue their side of things and explain from a host’s perspective why Airbnbs are not the devil per se, and how they can actually be good for a local community. What happened to them in Berlin is a result of the lack of market regulation. Local communities feel displaced and pushed out of the areas they come from by more affluent property owners and are angry as a result.

“Violence or threats are never the right path,” says Dre, “and don’t lead to solutions. We learnt that communication is key. When we started in Berlin, we didn’t tell that many people around us that we were hosts. But in Flieth, we took a different approach and involved the local community.”

I have learnt from other OutThere innkeepers on my travels that setting up a hospitality business in any small community can be something of a minefield. But, through their hard work and genuine likeability (along with some home-baked cakes), Dre and Gary gained the respect of their rural neighbours.

“I think people were most impressed by the fact that we did a lot of the work ourselves,” explains Gary. “It was lockdown and we were working outside every day, and the rest of the village could see that. When Dre did the paths, everyone was so moved by his dedication. He was on his knees for three months digging out huge boulders. So much so that he had to have a knee operation afterwards.”

“We were both always present and part of the village,” Dre interjects. “At first, our city sensibility made us unsure when people started to stop and talk. It just doesn’t happen in Berlin.”

“I was the more apprehensive, to start with,” says Gary. “I don’t really speak the language fluently and the locals don’t speak much English either. But everyone was so lovely, inviting us into their homes for tea and cake. I soon realised that, to return their hospitality, I should probably learn to bake. Now, given my embarrassment about not speaking German well enough yet, I probably overcompensate by baking cakes and gifting home-made jams made with fruit from the garden.”

“Jürgen next door has a become a bit like a grandfather to us,” adds Dre. “He’s lived here most of his life and has got a very well-established vegetable garden. He taught us things and gave me loads of seedlings for my first year. But he thought I was crazy for building planting beds. He found it funny that I was bringing in new soil, telling me ‘there’s plenty of soil here’. But over the years, he has actually started to realise that there are other approaches. We do our research on the internet, which he doesn’t do, so I’m learning new things and would argue that now he is quite impressed. It’s like when we used to work in London, you have to prove yourself and your ideas. It’s the same with being gay here. I’m sure that in the first few months he didn’t realise we were a couple. But I think you can change mindsets, slowly and by letting others set their own pace of change. It’s not your prerogative to alter their viewpoint, but I think that by fostering mutual respect, you can make some profound changes.”

Rainer and his partner Andreas, a school teacher, join us for dinner on my last night. Rainer designed the adjoining property’s garden. It’s heartening to see my hosts so central to the community here, not to mention bringing other queer people into their world and vice versa. Andreas created a series of workshops aimed at enriching local people’s lives by bringing in experts, including artists to do painting workshops. This in turn proved to be an inspiration for Gary, who is now developing the idea with his own network.

“It has changed our lives massively for the better. Both we and the dogs are really enjoying the space and being in nature.”

How they manage to maintain everything here and in Berlin, while ensuring all of it stays financially sustainable is clearly a lot. One could be forgiven for thinking it doesn’t leave time for much else. But not satisfied with creating one rural haven, they are already busy working on two other ventures in the area. They have bought a second house in nearby Neudorf and, as we go to press, are edging towards a deal to take a space at the Grosser Garten, where they can start to implement and test their ideas for new initiatives around food, wine, culture and learning.

It’s clear that Dre and Gary are no strangers to hard work and, insofar as I can tell, neither seems to have an off-switch. In addition to Hof Flieth, they both have other business commitments, which would overwhelm most people. Gary runs an AI company and Dre manages the couple’s extensive property-rental portfolio, which have found new fame latterly as filming locations.

I find their can-do attitude, which seems to be founded in process-driven realism rather than flights of fancy, frankly inspiring. Dre and Gary’s move to the Uckermark countryside is far from some kind of semi-retirement for these inherently energetic entrepreneurs. They see potential in so many aspects of the area and are clearly heavily invested, not just financially, but also in terms of their time and seemingly boundless energy. And for all their business acumen, there is something of the spirit of the socially minded principles of the German Democratic Republic in their philosophy, which Gary admits was one of the things that drew them to Berlin and also now Uckermark. The imprint that the GDR had on the culture, mindset, traditions and society in the region is quite unique.

Conversations with the couple about their plans range from socially conscious initiatives, such as teaching local school children, in particular girls, to code, utilising Gary’s extensive knowledge base in his AI business, to creating placements for budding chefs to incubate their restaurant ideas, and providing spaces for weekend getaways for business innovators. Gary’s distinctively Maltese traits of a deep sense of family, love of food, and a finely tuned business nose are complemented and supported by Dre’s stoic Polish work ethic, his tried and-tested organisational abilities, his natural creativity and eye for detail.

For Dre and Gary, the move to the country has been overwhelmingly positive.

“It has changed our lives massively for the better,” enthuses Gary. “Both we and the dogs are really enjoying the space and being in nature.”

“We were really surprised to have built a nice strong network here,” interjects Dre. “We have made more friends in our short couple of years here than we have in our whole time in Berlin. Also, the transition was so much easier than we thought. Initially, it was meant just to be a place to spend long weekends and to invite friends to stay. Then the pandemic forced us to spend much longer here, and we were surprised by how easy it was.”

“Any renovation project has its ups and downs,” confides Gary, “and it’s stressful, for sure, particularly when you’re running other businesses at the same time. Logistically, our lives are more complicated these days, since we still go back to Berlin frequently and, with three dogs, it can feel like a bit of a relay race at times, but it really is a minor aspect that’s overshadowed by the great benefits of the lives we’re building out here.”

Photography by Martin Perry