For all the spectacular natural beauty of The Islands of Tahiti, it’s the life force the inhabitants possess that draws Martin Perry to French Polynesia in a quest to regain his equipoise.

Winter 2021 was a particularly challenging time for me. There were many things in my personal life that were on a downward trajectory. My beloved dog had died, my father was seriously ill and we had been in the grip of the pandemic for what seemed like an eternity, which meant that my usual reset button – regular travel – could not be accessed. As a result, my ability to cope with everything that was happening was at an all-time low. It was affecting not only my relationships with others, but had also deeply shaken my relationship with myself. I felt under attack from what seemed like a relentless onslaught of negativity. I was drained. I wasn’t sleeping and I was, in a very real sense, losing my power and my sense of who I was in the world. I had withdrawn from life and lost touch with much that in the past had given me purpose. It made me realise just how important travel is for me. So, for my first big foray out into the world again, I made sure to choose extremely carefully.

The Islands of Tahiti conjure up an alluring image of paradise like few other places in the world, probably because of their remote location in the middle of the vast Pacific Ocean, midway between the Americas and New Zealand. The volcanic archipelago is dramatically majestic, as are neighbouring Moorea and the ‘desert island’ atolls of Rangiroa and Tikehau; their topographies alone make the 20 hours of flying from Paris worthwhile.

This story first appeared in The Thailand Rediscovered Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

But, as beautiful as The Islands of Tahiti are, their main appeal for me is something less tangible and obvious. There is an otherworldly, ancient and mysterious force at play here. Its presence can be felt everywhere. It is male, it is female, it is benevolent and nurturing yet, at the same time, it is fierce and uncompromising. It is in the strength of the volcanic rocks that form these land masses and in the sheer abundance of life in the bountiful rainforests that cover them. It is in the powerful, warm tropical winds that can suddenly appear from nowhere, then dissipate just as quickly. It is in the brooding, dark rain clouds and the intense deluges of life-giving water they can suddenly unleash, as well as in the intense rays of the sun that make it evaporate just as quickly.

It is in the dramatic waterfalls that cascade down hundreds of feet of rock into dark lagoons on the forest floor. It is in the colourful coral reefs that teem with an impossibly wide variety of sea life and form a natural barrier to the full force of the ocean, creating huge rolling waves that provide some of the best surfing in the world.

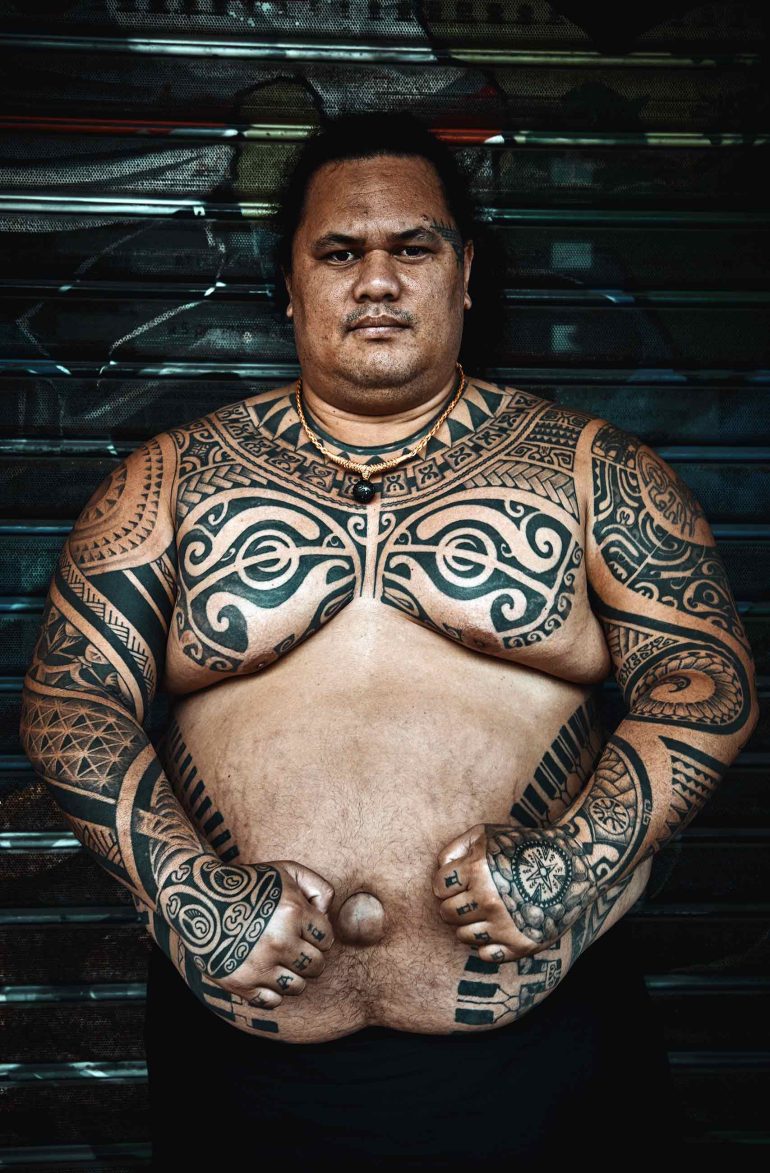

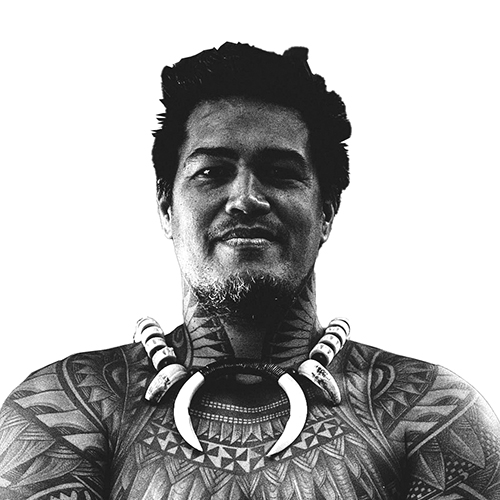

Tahitians believe that this power can be harnessed. They say that the same power is within each and every one of us. It is natural and spiritual, hard to define in words perhaps, but it’s a life force that surrounds us all. And when you encounter it, when you feel it, here on these dramatic islands, it makes total sense. Tahitians call it ‘Mana’ and it is unequivocally central to their culture, proudly celebrated in the magnificent tataus (tattoos) that adorn their bodies and in the sensual, flowing dances they still perform in traditional dress. But this, I learn, wasn’t always the case.

The revival of tatau

In the 1700s, both the Catholic and Protestant missionaries who settled on the islands in an attempt to christianise Tahitians fought hard to eradicate most expressions of local culture. They achieved this by poisonously associating traditional dance, dress and tatau with shame. Their repressive legacy lasted for the best part of two centuries and, as a result, many of the finer points of these traditions were lost. But in the 1980s, as part of a wider movement to reclaim Tahitian culture and identity, the art and – to a lesser extent – the ritual of tatau began to be revived. Today, most Tahitians once again proudly wear tataus. On the whole, the designs have been developed by contemporary artists who have reinterpreted the traditional carvings that make up the few surviving examples of pre-missionary Tahitian culture. Some of these artists have gained international fame and their work is highly acclaimed.

I’m fortunate enough to meet one of the most notable, Patu, whose studio is in downtown Papeete. It’s late afternoon and the road is buzzing with traffic and pedestrians. Over the course of our conversation, we are interrupted numerous times by people calling over from their open car windows or by passers-by coming up to greet him. Patu obviously garners as much respect from his community as he does in the international tattoo world. It’s easy to see why: he exemplarises the Tahitians’ reputation for being warm, welcoming and easygoing, and he exudes a calm, inner strength and authenticity that come from knowing who you are and having a connection to where you’re from.

In many ways, Patu is the embodiment of Mana, with a gravity that compels you to listen to what he has to say. He tells me how he has dedicated his life to honouring his culture and his ancestors and to harnessing Mana. Alongside his successful tatau practice, he also makes regular trips to spiritual sites, where he plays the vivo, a Tahitian nose flute. He shows me a video of himself at Marae Te Ti’iroa, a sacred site on Moorea. He’s in traditional dress, facing away from the camera, displaying his own magnificent tataus, his vivo emitting a haunting and beautiful sound, played to an audience of sacred trees that stand in motionless silence. A few seconds later, the forest suddenly comes alive as a strong wind runs through it, shaking the branches and leaves. Then, when Patu finishes playing, the trees return to their previous stillness.

For him, the video illustrates just how connected he feels to his ancestral home. It’s a connection that so many of us, myself included, have lost sight of; which, in turn, has led us into an unbalanced, disconnected and somewhat abusive relationship with the natural world. This connection to a higher force, and the certainty with which Patu believes in it, coupled with a solid, authentic cultural identity, are things I have little experience of. But I can see how they provide him with a sense of purpose and bring meaning to his life. They are the source of his power and, as such, he moves through the world in tune with his sense of self and of the Mana he possesses.

The coral gardeners

While some of The Islands of Tahiti were formed by volcanic activity, others were created by the build-up of ancient coral reefs, which developed into atolls large and small. Some are populated by thousands of people, some are uninhabited, yet others are home to just one or two hardy individuals who live off their natural bounty. One such atoll, Ahe, in the Tuamotu Archipelago, is the home to French pearl farmers Thierry and Caroline Bernicot and their son Titouan, who has spent much of his time, as you might expect, enjoying the sea. He has developed a love of surfing, freediving and underwater photography. But, like every teenager, he is connected to the world via social media and has gained a large number of followers who love the stunning photographs he posts of his underwater playground. It’s a world teeming with all manner of tropical sea life, which flourishes in the calm, shallow, warm habitat provided by the extensive coral reefs.

One morning, Titouan went out to find that much of the richly coloured coral garden he knew so well had turned white. Shocked and confused, he began to research what had happened and discovered that this coral bleaching was a result of a rise in sea temperature. Coral is made up of thousands of tiny animals called polyps, which use ions in seawater to make limestone exoskeletons. These play host to a type of algae (zooxanthellae) that grows on the structure and gives the coral its colour. Both organisms need the other in order to survive. Bleaching occurs when the algae become toxic to the polyps, which then expel the organisms, exposing the white limestone exoskeletons as the algae die. Coral reefs cover just 0.0025 per cent of the ocean floor, yet they generate half the earth’s oxygen and absorb nearly one-third of the carbon dioxide emitted by burning fossil fuels, but they are disappearing at a frightening rate.

Alarmed by his discovery, Titouan turned his attention to harvesting small fragments of healthy and more heat-resistant corals (or ‘super corals’) and re-populating them. Realising that this was too big a task to take on solo, he enlisted the help of a group of his surfer friends from neighbouring islands. Together, they harvested small pieces of healthy coral from the ocean floor that had become dislodged and reattached them to rocks using a home-made, water-resistant cement made of tree resin. They then tended to them in coral nurseries until they were large and healthy enough to replant on the reef, charting their progress on Instagram under the name Coral Gardeners.

The enterprise was very much a process of trial and error, but their success, in tandem with the sheer scale and urgency of the problem, spurred them on to develop new techniques and greater awareness. Under the passionate leadership of the charismatic Titouan, the Coral Gardeners kept pushing forward, looking for more innovative ways to develop their mission. But it soon dawned on them that this was something that would take more than they could achieve in their spare time. Dedicating themselves to the cause full-time, they tapped into the massive rise in awareness of environmental issues and started a global coral adoption scheme and volunteer programme.

“The Islands of Tahiti provided me with an opportunity to reconnect, not just with nature, but with myself, and to reflect upon my role in the world”

This proved a success and garnered the support of some very high-profile individuals, including actor Will Smith and freediving legend Guillaume Néry. Even eco-warrior Greta Thunberg has pledged her support and adopted a piece of coral.

I’m hearing all this inside the Coral Gardeners’ HQ on the island of Moorea, an hour’s ferry ride from Tahiti. Titouan and his friend Taiano are giving a well-rehearsed presentation that would rival any San Franciscan tech start-up looking for investment. But that’s no accident: rather than going down the well-trodden charity route and relying on a sparse pot of public money, they have taken an entrepreneurial tack, the aim being to act as quickly and effectively as possible to tackle the crisis. Their youthful exuberance and ‘can-do’ attitude, so characteristic of this interconnected, fast-moving generation, is inspiring, although the capitalist approach to environmentalism took me aback at first and I could feel my cynicism rising.

Questions about the morality of profiting from saving the planet started to form in my mind. They were followed by another thought: if it is a drive for profit that is destroying the earth, why not use that same motivation to do some good instead? The traditional approach of leaving weak, underfunded charities to mop up the mess left by resource-hungry super corporations clearly isn’t cutting it. The Coral Gardeners’ stated aim is ‘to empower people to create Coral Gardeners branches all around the world’. I can see how this model could be effective in other areas of environmentalism, allowing more and more people to be gainfully employed in projects that repair and safeguard the planet’s resources.

The Coral Gardeners now employ 24 highly invested people, most of them in their early twenties. Alongside the locals are foreign nationals from the cutting edge of the corporate world, including a strategist, scientists, and content creators, revenue and partnership people, as well as finance, HR, marketing and impact folk. There’s also an art director and they all work side by side with the gardeners themselves. At the top sit Titouan, as the hands-on, ‘face-of’ brand CEO, and CFO Thierry, who previously worked with Elon Musk. With this set-up, it’s not surprising that they are making waves. I come away truly believing that if anyone is to make a difference, it needs to be people from this generation. Poised to say goodbye, I ask what’s next.

“I’ll be speaking for the first time to the United Nations,” replies Titouan matter-of-factly.

I don’t doubt that this will be the first of his many appearances on the world stage. It’s this assured confidence that strikes me most about Titouan and his fellow crusaders: they are in touch with their inner strength and have come together with a common goal in mind. Instead of seeing a deeply worrying ecological disaster as a reason to despair and give up, it has given them focus and meaning. Their unshakable self-belief is unstoppable, hopeful and determined to bring about positive change. It is something that I could do to incorporate into my own life.

Choose life

Although our experiences of the world can differ greatly, the things that connect us – which are bigger than us, more permanent and yet somehow easy to ignore in our day-to-day lives – can become much clearer when we leave our usual surroundings and visit places and engage with nature. The Islands of Tahiti provided me with an opportunity to reconnect, not just with nature, but with myself, and to reflect upon my role in the world – from the impact that my over-consumption has upon our environment and how my environment impacts on me, to the energy I put out into the world whenever I interact with others, and how that affects my mood and ability to see my own worth.

We don’t all have daily access to majestic natural wonders or the slower pace of life of The Islands of Tahiti, but we can, if we are lucky, pay them a visit and bring some of it home with us. We can choose to be mindful of how we are in the world: to give more, make do with a little less, turn down the heating or the air conditioning a few degrees, and cycle or walk where possible. We can choose to pay less attention to the loud voices of the producers of consumable goods and tune in to those pointing out serious concerns, such as sustainability and workers’ rights. But we can also choose to silence the unhelpful voices within us and learn to understand that fostering a sense of meaning and connection can have a powerful impact on our lives and the world in which we live. We can choose to harness the power within each of us – call that what you will. I know from my personal experience that to forsake it, or to all but deplete it, comes with a real risk of losing everything – ourselves included.

Martin flew to Tahiti with Air Tahiti Nui. To find out more about The Islands of Tahiti, visit the destination’s official website.

Photography by Martin Perry

Get out there

Do…

… get a PADI qualification before you go to The Islands of Tahiti or while you’re there. The diving is some of the best in the world.

… support the efforts of the Coral Gardeners in restoring the dying reefs around Moorea, one of the most biodiverse eco-systems in the world and currently under threat from rising sea temperatures.

… try out quad biking with the Moorea Activities Center. It’s an exhilarating way to experience the Jurassic Park-like jungles of Tahiti that lead up to the panoramic Belvedere Lookout.

Don’t…

… worry about what you’ll be able to bring back as a souvenir. The islands are home to pearl farms and the distinctive black pearls come in a wide variety of forms and sizes, making them unique mementoes.

… miss the chance to learn more about Polynesian flora and fauna by visiting the immersive Te Fare Natura eco-museum on Moorea.

… forget to bring your spirit of adventure. The Islands of Tahiti have so much to offer those looking for a truly extraordinary holiday, not only in terms of natural wonders but also because of their rich culture and history.

The inside track

Vaitea Etilage is an adventure lover who gave up a nine-to-five office job to set up the Safari Islander. He is now one of the most prominent guides in Tahiti and spends his days sharing his love of the islands’ treasures on a variety of itineraries that take in cultural and natural wonders.

Visit

The three cascades known as Faarumai Waterfalls are a must. Vaimahutu is the first, then it’s a 20-minute hike to Haamarere Iti and Haamarere Rahi falls. Don’t forget your towel, as you won’t need to get into the water to get wet.

Surf

Serious surfers will be challenged by Teahupo’o’s formidable waves. For amateurs, Taharuu Beach offers some rewarding and less dangerous rides. You can surf off the beach without needing to boat out of the lagoon.

Eat

The food trucks (‘les roulottes’) in Vai’ete Square, Papeete, will blow your mind. It’s a local claim to fame that this is the origin of food-truck culture. Whether that’s true or not, you can get a very good meal at a decent price.