The Donald’s downer on diversity in the arts hasn’t cowed Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, which is about to launch the major new exhibition City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago. Spanning four decades of resistance and representation, it’s the passion project of curator Jack Schneider, who tells OutThere why and how he wants to bring new recognition to a generation of courageous creators.

Right now, shockwaves are coursing through the US’ progressive arts scene. On the very first day of his second term as president, January 20, 2025, Donald Trump signed executive orders that have led to the defunding of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives across the country. Exhibitions and performances featuring artists from underrepresented communities have been cancelled, federal arts funding for any form of ‘gender ideology’ is now banned and thousands of grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) have been repealed.

So it’s heartening that City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago, a new exhibition at the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), will open as planned on July 5.

First opened in 1967, and one of the world’s largest contemporary art museums, the MCA, whose home today is an elegant 1996 building by Berlin architect Josef Paul Kleihues in the central Streeterville neighbourhood, has a strong track record of supporting queer artists. Frida Kahlo’s first US exhibition took place here in 1978; Nicole Eisenman and Christina Quarles are among boldly LGBTQ+ artists to recently have solo shows, and Robert Mapplethorpe, Nan Goldin, Isaac Julien and Mickalene Thomas are among the many LGBTQ+ artists with work in the permanent collection (you can discover more about the collection’s queer works in Jack’s essay Cruising the Collection: Queer Images at the MCA at www.mcachicago.org).

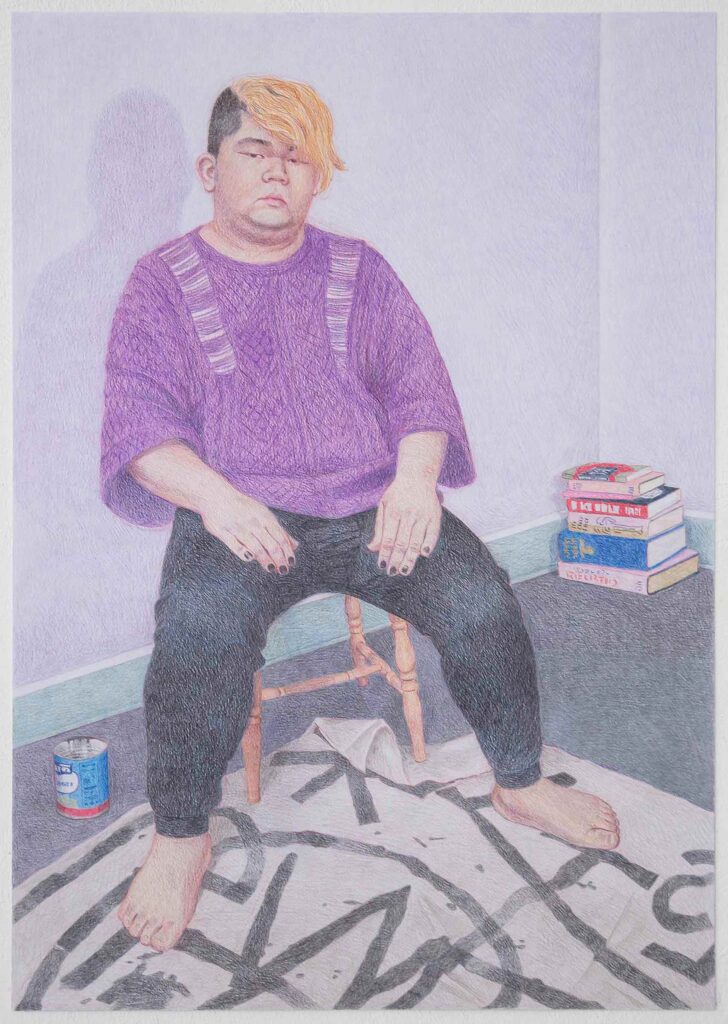

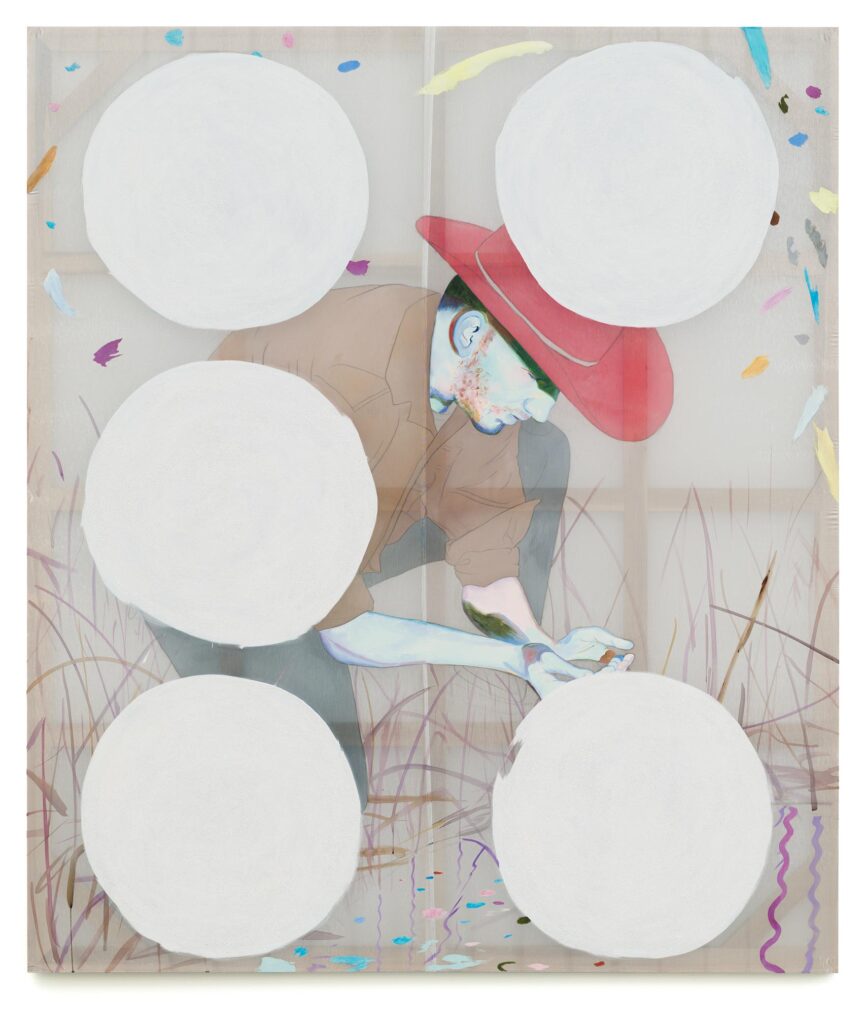

The new exhibition, which runs until January 25, 2026, traces four decades of as yet undersung queer art and art activism in the city through painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, performance and more. Exploring work from more than 30 artists and collectives starting in the mid-1980s, when artists and activists raised their voices in protest at the government’s calamitous handling of the HIV epidemic, it celebrates many ways in which diverse creators have, then and since, sought to imagine and realise a utopian, equitable new future for their city.

Its curator is Jack Schneider, a Minneapolis native who moved to Chicago 14 years ago to study at the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Immediately enamoured of the city’s energy, accessibility and collaborative spirit, he never left. Also co-founder and co-director of the independent, artist-run space Prairie in the city’s Lower West Side, he tells OutThere that the two years he has spent working intensely on the show, the most complex he has ever curated, represent just a fraction of an eye-opening self-education.

What are your aspirations for City in a Garden?

In a nutshell, the show looks at Chicago’s essential but often under-acknowledged role in the stories of queer art and activism. To read about queer art history as it’s currently written is essentially to read about what happened in New York and to a lesser extent, San Francisco and Los Angeles. But obviously a lot happens between these coastal meccas. And I’m kind of taking Chicago as my case study, and trying to expand knowledge around queer art history by looking at a location that has been overlooked.

How did the project take shape?

While I’ve been working on the show in earnest for two years, this is a topic I’ve been researching informally for a very long time. The most significant lender of work to the show is Dr Daniel S. Berger. He became quite famous in the 1990s when research he was working on led to the first life-saving combination treatment for HIV. Since then, alongside his medical work, he has been developing an incredible collection of work primarily by queer and black artists, because those were the two demographics most affected by the AIDS pandemic, and in 2010 he opened a space called Iceberg Projects at his house in Rogers Park. That’s how I was first introduced to the really rich legacy of queer art in Chicago, and I’ve been researching it ever since.

Which artists have been some of your favourite discoveries while preparing the show?

I’m really excited about a series of photographs we’re including called Marginal Waters by Doug Ischar. It’s a simple set he took at a place called the Belmont Rocks, which was a sort of semi-public gay beach on the North Side before there was anything close to an officially sanctioned gay beach. And it wasn’t really a beach. It was essentially a set of limestone breakwater rocks along the lakefront where queer people just sort of decided, ‘This is where we hang out. This is our outdoor public space.’ And he took gorgeous photographs of the people who hung out there.

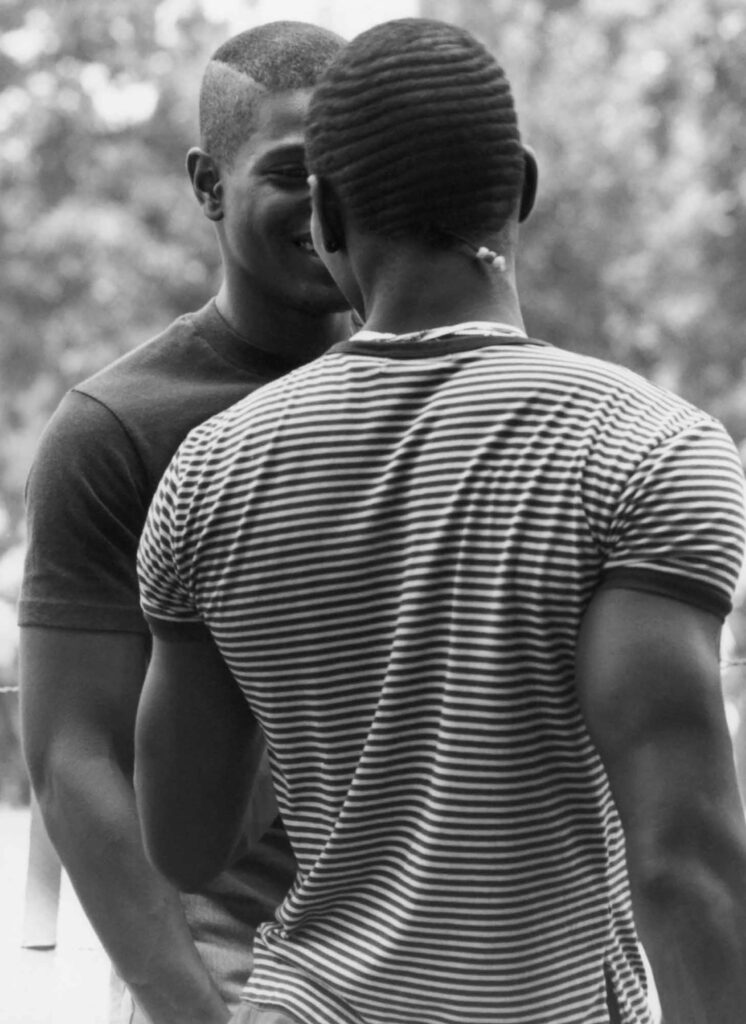

Then there’s a series by Patric McCoy, who was photographing the black men for men scene downtown and on the South Side. I wasn’t familiar with his work before I started this project; he was actually an environmental scientist, and taking these photographs was his hobby. And they are incredible, as good as work by any artist who’s been calling themselves such in the last 40 years. Side by side these two sets highlight something interesting about Chicago, that, for all its diversity, it’s still a very segregated city, although the queer community is a bit more inclusive.

What format does the exhibition take?

The exhibition proper will be across the Sylvia Neil and Daniel Fischel Galleries. But we’ve also extended the show out into the atrium, where there will be a large new mural by the artist and activist Edie Fake called Free Clinic for Gender Affirming Care. And we’re bringing back a series called Primetime, which we haven’t held since before Covid, because it’s a social event, basically a big party in the museum. We brought it back specifically for this exhibition because it felt so important to embrace nightlife, which is represented in so many of the works. It’s about being together. It’s about dancing, about performance, about drag, So we’re partnering with the club Smartbar, and specifically their legendary Sunday night LGBTQ+ night, Queen for a Primetime event.

What was your route into curation?

To call it accidental wouldn’t be quite right. After studying studio art as an undergrad, I envisioned myself becoming a studio artist as a career. And a couple of years after school, when I was showing my work, nine times out of ten it was at an artist-run independent gallery. Chicago has a really rich history of artist-run spaces that support a robust scene. So in 2017, an artist named Tim Mann and I decided to start our own space, Prairie, to contribute to that. Honestly, kind of selfishly, I thought at first that Prairie would raise my profile as an artist, but I found I enjoyed working with other artists and organizing exhibitions even more than my own art practice. That was my introduction to curatorial work. So then I started looking for opportunities professionally, and particularly at the MCA, because of all Chicago’s institutions, I felt the strongest connection to its programme. I started working here in 2018, and in my time here I’ve been able to work with some really iconic queer artists.

How would you characterise Chicago’s contemporary art scene overall?

For one thing, it’s still relatively affordable compared to New York or LA, so there’s a good influx of artists. Behind those two cities, I’d say it has the US’ highest artist population. And the art scene here is much less competitive and commercial, and has a much more collaborative attitude, so people are more willing to experiment and support one another.

And the diverse range of institutions and art spaces here means that a really wide range of types of art are being made. Aside from the bigger places, like us and of course the Art Institute of Chicago, there are fantastic mid-scale organisations like the Renaissance Society, Graham Foundation and Stony Island Arts Bank that champion more experimental work. Wrightwood 659 is also an amazing space, only seven years old. It has a historic red-brick façade that the gallery wasn’t allowed to touch, but beyond is an amazing, minimalist concrete and brick building by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando. Its focus is on queer and East Asian art.

Then there’s a whole range of smaller, artist-run spaces where emerging artists can show pretty much what they want and try out new things, and that scene continues to be really healthy.

Have you personally felt intimidated by the current administration’s hostility to DEI in the arts?

Professionally, we’re quite insulated from the anti-trans, anti-DEI pressure, because the vast majority of our funding is private philanthropic dollars. But I speak to colleagues across the country whose funding and support are embattled and who are being pressured even to not use certain language around those issues. Chicago is a city of huge diversity in everything apart from politics. We’re historically deep blue, and a very liberal city, and I feel lucky and grateful we have a community that will support a project like this. In fact, I think they are even more supportive because the cultural landscape across the country is becoming less conducive, and I feel, since the election result, the show has taken on a new purpose – to speak truth to power.

Given Chicago’s staunch Democrat track record, what is the mood in the city right now?

In the first few months after the election, there was a general sense of defeat. That it had happened a second time, it wasn’t an aberration, it wasn’t a fluke. That there is something entrenched here. But in the last couple of months, there’s a feeling that more people are getting galvanised and figuring out how they want to respond. The ‘No King’ Day protest, for example, was massive in Chicago. That response, that resistance hasn’t fully formed yet, but what I feel is that right now we’re at a moment of formation.

Photography courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Doug Ischar, Patric McCoy, and by Nathan Keay at MCA