Keen to try African food in Paris? From homely beginnings in the city’s long-established immigrant communities, the cuisines of the diaspora have in recent years proudly taken their place in mainstream Parisian gastronomy, whether via funky fusion-food trucks, casual lunch spots or Michelin-starred destination dining.

I’m sitting in Bomaye restaurant on Rue de Paradis in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. The intense orange-and-yellow walls and ceilings are covered in bold, Africa-themed murals. I’m here with Jacqueline Ngo Mpii, the Franco-Cameroonian founder and CEO of Little Africa, a multimedia agency and cultural space that promotes African culture in Paris. White twentysomethings with tattoos and multi-coloured teddy coats enter and take their seats. On the next table, a group of young black women are reading tarot cards and ordering burgers with names like Kin La Belle, inspired by the Kinshasa dish poulet mayo (barbecued chicken mixed with mayo and spices).

Selecting from the funky online menu, I go for Le Lion de la Teranga, whose onions and tangy lemon sauce are drawn from poulet yassa, the classic Senegalese dish of spicy chicken in an onion, mustard and lemon marinade.

Infused with Sub-Saharan flavours, Bomaye’s African burgers are a hit and reflect the growing popularity and mainstreaming of African cuisine in Paris in recent years. The restaurant was launched in 2021 by Camille Gozé and Laurent Kalala, two of several entrepreneurs whose more outward-facing approach over the past decade has brought African cuisine to downtown neighbourhoods.

This story first appeared in The Paris is Turning Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

It’s quite a change. Before 2013, one generally had to venture to the 18th arrondissement or the outer banlieues to eat dishes such as attiéké (Ivoirian couscous-style cassava with braised meat) or poulet DG (director general chicken), a Cameroonian dish of chicken and fried plantain in a vegetable stew.

“When I grew up, going to an African restaurant meant going to Château Rouge,” says Jacqueline, referring to Paris’s ‘Little Africa’ neighbourhood in the 18th, “but I don’t consider those African restaurants. What we have there are maquis.”

She’s referring to cheap and cheerful African eateries started up in the 1960s and 1970s by immigrants and catering to an entirely African, local clientele. The popular Chez Zeyna is an example. Its crammed interiors are the venue for consuming mounds of Senegalese thieboudienne (fish, rice and vegetables) presented in motherly, unlandscaped heaps. These go down well with diners, but not so well in the glossier world of restaurant marketing.

PR is an issue for African cuisine, which is often perceived by non-Africans as ‘too spicy’, ‘swimming in palm oil’ and ‘unglamorous’ and prepared in dark kitchens of dubious hygiene. Mindful of those perceptions, the first generation of African immigrants often lacked the confidence to show off their cuisine outside their communities.

This left Sub Sahara the only terra incognita left in Parisian gastronomy, says Anto Cocagne. Born in Paris to Gabonese parents, Chef Anto is a renowned private chef who won the Eugénie Brazier Prize for creativity and is hosting a TV culinary show this autumn called L’Afrique a du Goût.

“Lots of French people know the different continents,” she says. “It’s easy to go to Asia or North or South America, but in parts of Africa it’s difficult, because tourism is not really developed. And people have a bad image of Africa, its wars and poverty. But now we have a lot of TV cookery shows in France. We have a lot of African people using African products. People are now really curious about our spices, products and recipes.”

The mainstreaming journey began with pioneering chefs such as Cameroon-born Alexandre Bella Ola, who was the first to popularise African cuisine through TV shows. He opened a restaurant in the Parisian suburb of Montreuil and trained with renowned chef Joël Robuchon before releasing his award-winning cookbook Cuisine actuelle de l’Afrique noire in 2003. In his wake, a new generation of diasporic chefs has emerged, many born in France and trained at elite cooking schools such as Lenôtre, Ferrandi and Institut Paul Bocuse. They began crafting cuisine that was more ‘gastronomique’ and ‘décomplexée’ (stripped of inhibitions), plated up in a modernist style and slickly marketed. “People thought, ‘Wow, African cuisine can look much more beautiful’,” Jacqueline enthuses. “It was artistic.”

Most notable was Olivier Thimothée, a man of Martinique-Algerian extraction, who launched his Waly-Fay restaurant in the Bastille neighbourhood in 1997. A diverse crowd has kept its industrial-chic interior buzzing ever since. Given the toughness of the Parisian foodie crowd, such longevity is an achievement and a reflection of high standards I can attest to – my poulet yassa (tender chicken with a zingy lime sauce) was sublime.

Thimothée’s high bar has inspired other African food masters to raise their game. The current chef du jour is Mory Sacko, a 31-year-old of Senegalese-Malian descent, who is making a name for himself with his Afro-Japanese fusions. Honoured with the Michelin Guide’s Young Chef Award in 2021, Sacko opened his restaurant MoSuke the following year, and within weeks was awarded a Michelin star for African dishes mixed with Japanese ingredients – palm oil substituted with miso in his mafé (peanut stew), for example.

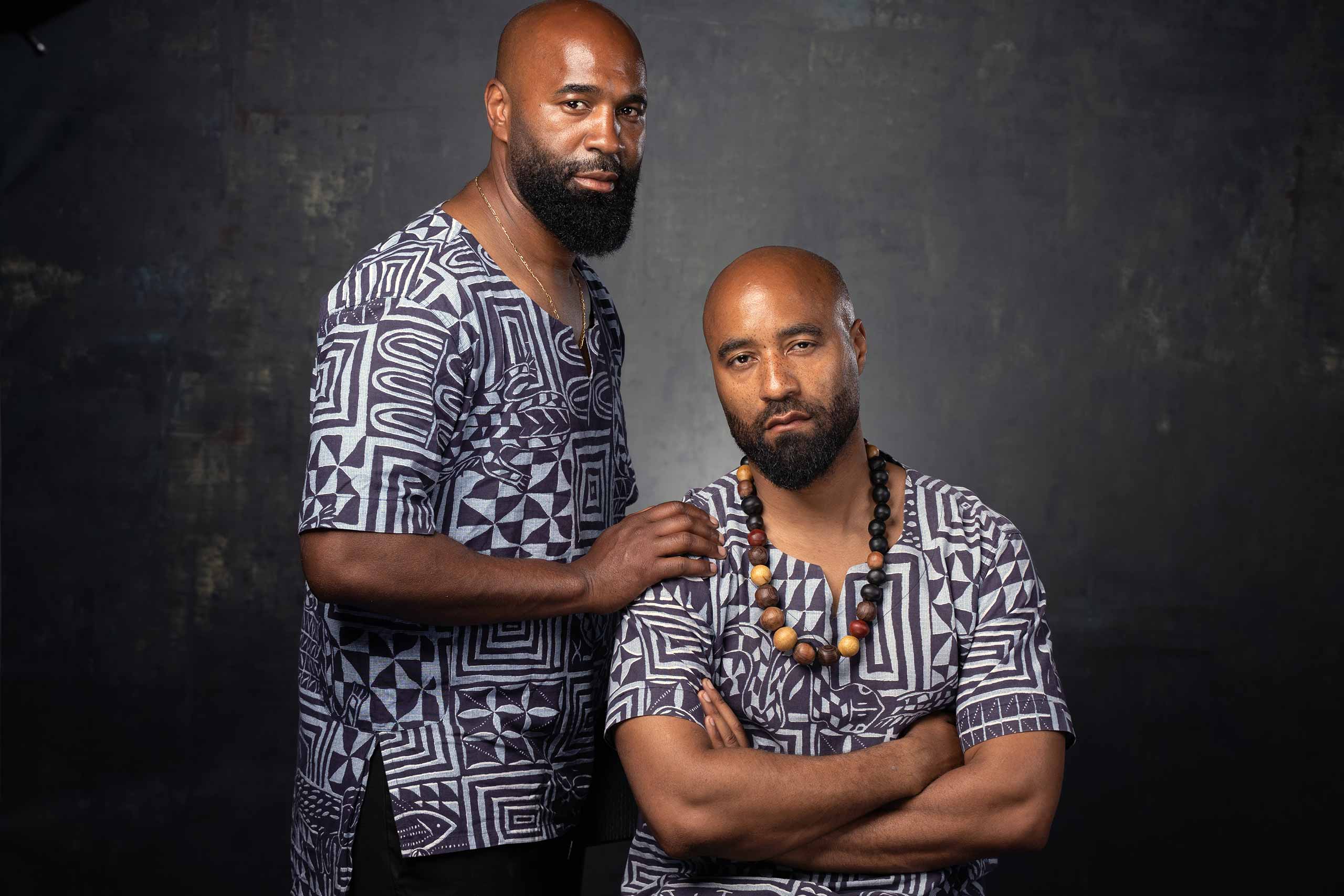

A growing number of entrepreneurs have taken the fusion route. New Soul Food, run by twin brothers Rudy and Joël Laine (Guadeloupean father, Cameroonian mother), began as a food truck planted in the business district La Défense, blaring out music while serving Caribbean-African dishes to a snaking line of customers. The twins have since launched a bricks-and-mortar restaurant, New Soul Food Le Maquis, by Canal Saint-Martin in the trendy 10th arrondissement. Amid hip Afro interiors, waiters wearing ‘Black Food Matters’ T-shirts serve dishes such as braised chicken with attiéké, candied tomatoes and ‘Afropean’ yassa sauce. The food has distinctly African roots, but contains New World elements that attract a very diverse clientele.

This more mainstream appeal is something Chef Anto approves of. “My guests are white,” she says. “They don’t know anything about African products. And if I want them to, I need to use their language – French cuisine – to improve the presentation. So I use French techniques, but I try to conserve the African flavour because if I change the taste, it is not really African.”

This focus on a non-African audience is evident at BMK restaurant, one of Paris’s best-known African restaurants and the brainchild of Fousseyni Djikine, a former business consultant of Malian heritage. He and his brother Abdoulaye are on a mission to educate their customers about their products and their origins. I head to one of their two branches, BMK Folie-Bamako, in the 11th arrondissement. Its interiors have a relaxed hipster vibe, with ochre walls, African-mask light sconces and cushions upholstered in African fabric. Chilled Afrobeat pulses gently in the background. A shelf displays BMK’s gorgeous cookbook, which showcases recipes from across the continent, from Mali and Uganda to Somalia, supplemented with cultural information. Their books, website and restaurants are all part of their broader mission to teach people about their culture. The marketing is aimed at non-African customers – in fact, I’m the only black person in here among white and Maghrebi customers chowing down mafé and zaame (vegetable rice).

An increasingly non-African clientele is something Chef Anto notes, too. “When I gave classes in Paris five years ago, there were only people from Africa or the diaspora,” she says. “Today, when I give an African cooking class, it’s only white people. Sometimes I ask them, ‘Why do you want to learn about African cooking?’ They say, ‘Because we saw some products in the grocery store, but we don’t know how to use them,’ or, ‘My daughter-in-law is from Africa and I want to cook something for her’.”

Appealing to non-Africans has created an inevitable though relaxed tradition-versus-innovation divide among chefs. Paris-based Senegalese culinary blogger Aistou M’Baye tells me she prefers to keep to traditional recipes and flavours. The 34-year-old developed a big social-media following after setting up her blog, which champions the health benefits of African products such as millet and sorghum. Aistou also runs a cookery school to teach innovative ways of cooking with them. She says that in the past three years, mainstream supermarkets have begun stocking African ingredients such as okra, scotch bonnet chillies and fonio, an ancient African grain. White chefs are also dabbling with African ingredients, putting hibiscus in pastry, or baobab fruit powder in pastries, or using fonio in place of couscous.

And the new interest is not just about African flavours. Many on the scene believe the continent can lead the way in nutritional health. “Afro veganism hasn’t been covered enough,” says Jacqueline. “A lot of the food, when you look deeply, is not meat. It’s street food such as roasted plantain.”

Cameroonian-born Nathalie Brigaud Ngoum agrees about the health focus. The charismatic chef, blogger and cookbook author – who always wears a trademark African-print chef’s hat – creates recipes such as plantain pizza with ndolé (stewed nuts with bitter leaves and fish or beef), sometimes without gluten, butter or refined sugar. She replaces flour with tiger nuts and uses baobab powder as a tasty source of vitamin C. Athletes now consult her on nutrition. “There are people who have known for years that the region is good for healthy foods, but they didn’t want to give the credit to Africa,” she tells me when we meet for lunch at BMK Paris-Bamako in the 10th. “It’s sexier for them to say ‘India’. And then there are people who are now willing to learn.”

On the plant-based tip, the funky, evenings-only L’Embuscade, in Pigalle, offers a ‘100 per cent Afro vegan’ menu of authentic and fusion dishes created by chef Phoebe Dunn, a Brit with a Nigerian father who planned to launch a food truck until she met the owner Patrick Ossié. Their dishes make much use of local produce and ethical African farmers – and are complemented with killer cocktails and Afrobeat DJs whipping up a party downstairs.

It’s a remarkable evolution. But for all the talk of superfoods and Michelin stars, sometimes it’s the lowbrow stuff that’s the benchmark of progress. My Parisian friend sent me a link to frozen-food company Picard, whose products – she says with a giggle – are secretly defrosted by bougie Parisians for dinner parties. They now have a new ‘ethnic food’ range. And what’s in it? Poulet yassa and mafé au poulet ready meals – a sign, if more were needed, that African cuisine is embedded in Parisian culture.

www.bomayeclub.com | www.walyfay.fr | www.mosukerestaurant.com | www.newsoulfood.com | www.bmkparis.com | www.lembuscade-restaurant-paris.eatbu.com

Photography by Martin Perry, Pepa, Virginie Garnier, Milena Carranza and courtesy of New Soul Food. Flyer designed by Kart Gable