With banlieue art, a fresh dynamism is reinvigorating Paris’ contemporary art scene, fuelled by pioneering spaces in once-marginalised outer suburbs. Its secret sauce? Accessibility and diversity, as our writer’s own arc from gallery-launch DJ to international artist-curator exhibits.

Long before I arrived in France, my initial encounter with Paris’ ‘banlieue’ scene came, in my native South Africa, through the Saint-Denis Style remix of rapper Nas’ 1995 song Affirmative Action, featuring the French group Suprême NTM. The French rappers’ home turf, Saint-Denis, is a suburb just north of Paris with a history of deprivation and high crime rates. On Nas’ track, they rap, ‘Chacun sa mafia, chacun sa mille-fa’, a phrase that, via ‘verlan’ slang, translates to, ‘to each their mafia, to each their family’. This exposure set the stage for deeper exploration, not least through Mathieu Kassovitz’s ground-breaking film of the same year La Haine, whose stark portrayal further probed the tension, danger, resilience, and community of life in the working-class, multicultural banlieue – literally a neutral word, but in Paris imbued with associations of poverty, crime, unemployment and violence.

The banlieue – specifically the north-eastern suburb of Pantin – became my first home here after a sudden and unplanned move from London in 2008. As Mo Laudi, I’d spent ten years in the UK capital building a career as a musician, MC and DJ, pioneering Afro-electronic genres. I’d MC’d with Radioclit, performed alongside Major Lazer and Miriam Makeba, ran the regular club night Joburg Project and was gigging regularly all over the UK and internationally. And despite a reputation for being unwelcoming, Parisians embraced me in the world of nightlife, and before long I was DJ’ing at Favela Chic Paris, the Ritz Paris hotel and Le Social Club, even MC’ing there with Suprême NTM’s Joey Starr, with Daft Punk’s one-time manager Busy P on the decks.

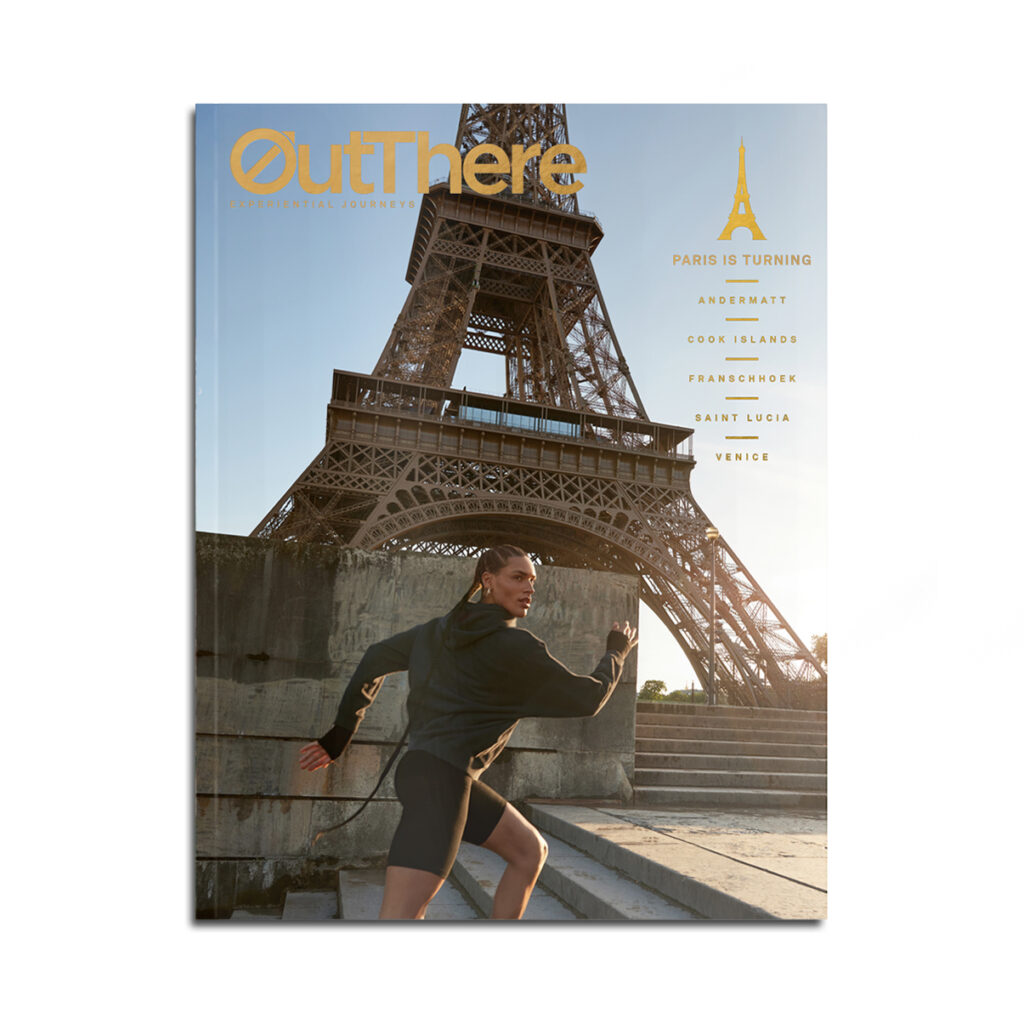

This story first appeared in The Paris is Turning Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

It was as a banlieue resident, my eyes were opened to the city’s unspoken social stratifications, signalled subtly through ‘arrondissements’ – Paris’ postcode-defined neighbourhoods. Locals would often ask me which I lived in. ‘Neuf trois’, I’d say of my address in the 93, which to my surprise elicited the response, ‘That’s not Paris’. One stop beyond the Péripherique ring road was a no-no. I later lived in Paris ‘proper’, in the 3rd, 5th, 10th, 11th, 16th, and 19th arrondissements, only to come back to the 93 years later, for more space. And things have changed.

So too, in that interval, has the trajectory of my life. As a South African DJ, I’d get asked by friends and colleagues to recommend places to go for South African visual artists visiting Paris, and I started to make connections in the art world, often getting booked to DJ at gallery launches. I’d specialised in graphic design on my art direction course at AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg, and had always designed covers and flyers for my music, but had never officially worked as an artist. In 2019, the French-Caribbean artist Julien Creuzet asked me to create a soundtrack for an installation he was exhibiting in the Palais de Tokyo, and more collaborations soon followed. The same year, I was invited to create a sound installation for the group show Ernest Mancoba: I Shall Dance in a Different Society at the Pompidou Centre, and by 2021, I curated the exhibition Salon Globalisto at Bonne Espérance Gallery, becoming the first black South African curator to organise an exhibition in Paris. My practice has grown to encompass painting, sculpture, video, collages and more. I’ve had a solo exhibition in Barcelona, taken part in 19 group shows, and in 2025 will co-curate my seventh show, Afrosonica, at the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève, with Madeleine Leclair.

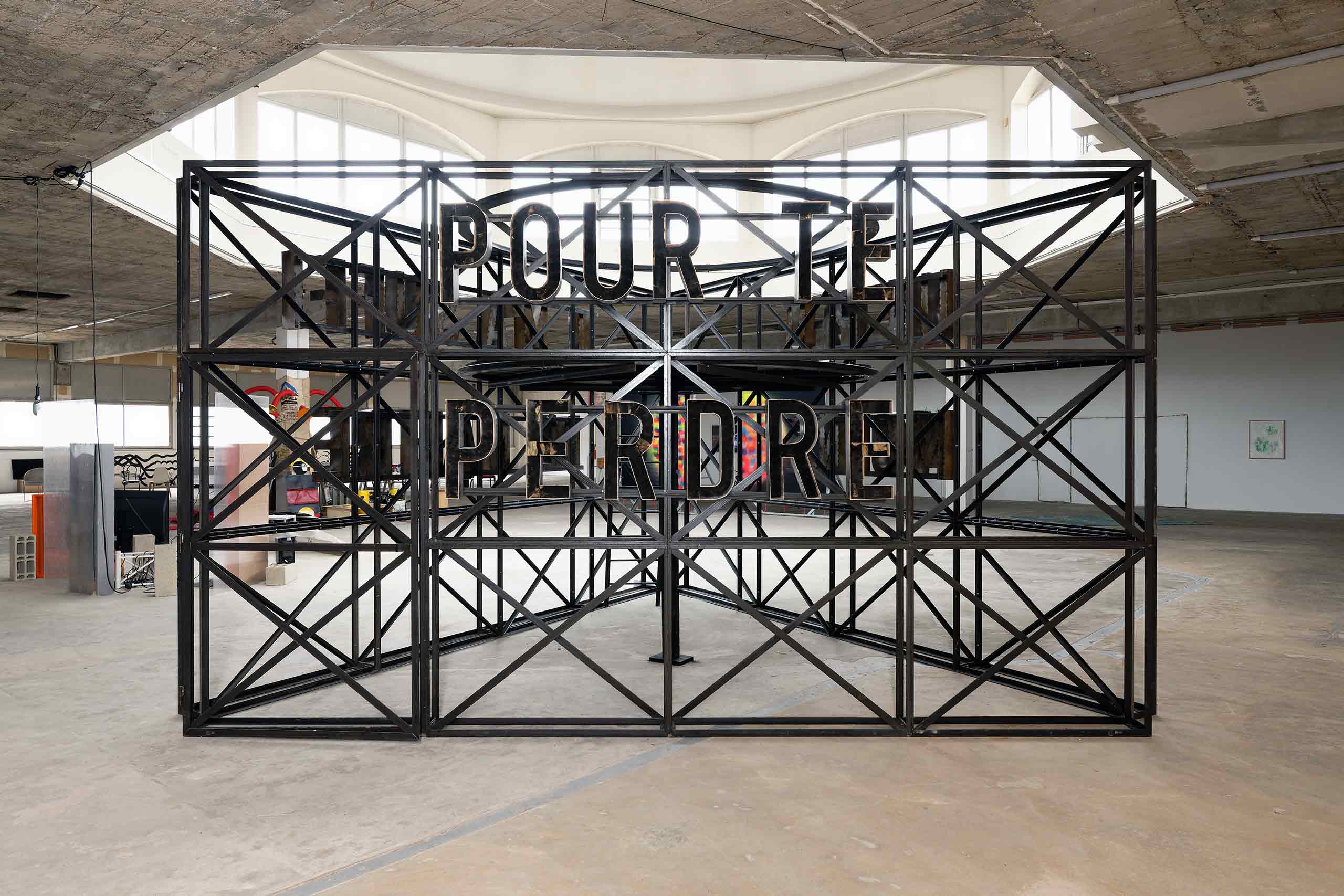

This has coincided with a shift in Paris’ contemporary art scene that has seen its focus shift beyond the Péripherique, transcending the restrictions historically imposed by the city’s high rents and traditionalism to begin to embrace all the nuanced cultural potential of the diverse metropolitan population, which is the true identity of Paris today. Emerging artists now have radical new platforms that allow them to affordably create work, network and learn career-building new skills, courtesy of a range of new living, working and exhibition spaces rooted in their multicultural banlieue communities, and especially in the north-eastern suburbs of Pantin, Romainville and Aubervilliers, where I now live. And the global cachet of Paris’ contemporary art is higher than it has been in many years, as the inauguration of Paris + by Art Basel in 2022 seems to confirm.

Romainville’s Fiminco Foundation, for example, both nurtures emerging talents and magnetises Paris’ art crowd to come and discover them. Funded by the commercial real estate company of the same name, the smart campus, a rehabilitated pharmaceutical factory in tended grounds, encompasses exhibition spaces, galleries and free live/work spaces for artists supported by its extensive residencies programme. One section brings together five established galleries – Air de Paris, Galerie Sator, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, In Situ Fabienne Leclerc, 22,48 m2 – and frac île-de-France visitable storage spaces under the umbrella name Komunuma (‘community’ in Esperanto), and more of the huge site will soon host projects connected to cinema and theatre.

I worked with In Situ to borrow the work of Otobong Nkanga for the Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux exhibition I curated at the Musée d’art contemporain in Saint-Étienne, which has France’s second biggest collection of modern art, in 2022. “I didn’t like what was happening in the centre of Paris anymore,” says In Situ’s director Fabienne Leclerc. “There was this very bourgeois atmosphere. We wanted to find an industrial building. I never doubted; I was absolutely convinced it would attract the right people. Our artists like the space, and they like the spirit.

“As for the bourgeois of the 16th arrondissement who don’t know what to do after tea, I don’t mind. A lot of serious, interested, motivated people come here, and love it because it’s a mix of a private foundation and a residence. People come from all over the world. Two more galleries will move here later this year and much more is planned for the site.”

Jocelyn Wolff, whose gallery is next door, expresses similar sentiments. “It’s a new concept to have art spaces in the banlieue instead of the historical centre. It’s still a process for Parisians to understand that they don’t live in a city of just two million inhabitants. The last time the administrative definition of the city’s borders was expanded was in the 1870s, and since then, everything has been frozen. I think that as art galleries, we should not be frozen. We should also approach the territory by slightly enforcing its development. I very much like the idea of having a space in part of the city that is developing and changing, and where people actually live, unlike, for example, the 8th. That’s why people come when we have openings. It definitely works.”

Aubervilliers alone is home to multiple spaces and initiatives purposefully nurturing emerging artists through affordable studio spaces that invite creatives into broader cultural communities, and also conduct active outreach work and support local economies. With the stated aim of creating a creative and cultural neighbourhood, POUSH is a 20,000 sq m (215,000 sq ft) industrial campus with buildings that date back to the 1920s, and as well as offering subsidised spaces for 270 artists representing more than 30 countries, provides them with production and communications support, and spectacular exhibition spaces. Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers too offers spaces for research, creation and experimentation, with a specific focus on innovative collaboration, while Le Houloc is an artists-founded non-profit where sculpture, photography, painting and video are made and shown.

A striking monument to Aubervilliers’ rude artistic health, on its border with the 19th arrondissement, is Le19m, a dramatic, 25,500 sq m2 (275,000 sq ft) building by Rudy Ricciotti with an exoskeleton of concrete ‘threads’ inspired by a vertical textile weft. Home since 2021 to more than 600 employees of Chanel’s Paraffection subsidiary group of maisons d’arts, it also has a free, 1,200 sq m (13,000 sq ft) exhibition space that celebrates arts and crafts through exhibitions, workshops and talks.

In fact, this pedigree is not entirely new. Aubervilliers was for a long time a communist stronghold (hence its nickname ‘banlieue rouge’) with a welcoming strategy towards the arts. Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers’ history goes back to 1993, and Thomas Hirschhorn made a ‘neighbourhood project’ here at their invitation in 2002. Today, I have among my neighbours many fantastic artists, among them Agnès Geoffray, Marianne Mispelaëre, Lionel Sabatté and Nicolas Boone.

Neighbouring Pantin is also home to many galleries, including The Community Centre, another grass-roots space committed to supporting experimental work. At the other end of the spectrum, and a symptom perhaps of the gentrification accompanying more and more professionals’ exodus from central Paris (and visible in the huge amount of construction projects all over the 93), is Thaddeus Ropac, a sister site to the Austrian gallerist’s longer-established central-Paris space in Marais. Here, exhibited artists are more emerged than emerging, and already commanding world-class prices. The last time I was there was for the opening of Venezuelan-born, London-based artist Alvaro Barrington, who currently has a major exhibit in Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries. In the crowd, there were various art-world celebrities, including Dame Julia Peyton-Jones, formerly director of London’s Serpentine Gallery and now Senior Global Director across Ropac’s Paris, London and Salzburg galleries.

Another indicator of the banlieue effect’s rippling resonance has been the opening in 2012 of an outpost of global art behemoth Gagosian, a little further north-east in Le Bourget. With stellar names like Theaster Gates, Richard Serra and Takashi Murakami among recent exhibitors and its location next to Europe’s busiest private-jet airport, it neatly illustrates the breadth of the range of art creators and consumers now operating in this new territory beyond Paris’ Péripherique.

And the effect is two-way. Known for his love of the suburbs and street art, curator at the prestigious 16th-arrondissement Palais de Tokyo, Hugo Vitran, this year gave Mohamed Bourouissa a huge solo show, Signal. Born in Algeria, Bourouissa grew up in Paris’ disenfranchised banlieue, and his work highlights the complex histories and resilience of disempowered communities, and their struggles against colonial dominance. Capturing moments of both tension and triumph, Signal is particularly poignant in the context of Paris’ shifting relationship with its outer suburbs, and invites all echelons of the city’s community to engage meaningfully.

For a new generation of artists, the new opportunities and networks the banlieue are enabling are proving transformational, while bringing to the city’s art scene unprecedented diversity. Brazilian artist Daniel Nicolaevsky Maria says of his 11-month residency at the Fiminco Foundation last year, “During my fellowship, I had the invaluable opportunity to focus on my research, refine my artistic skills alongside a dedicated team committed to supporting early-career artists, and bring to life my most ambitious project to date – the installation Cradle of the World. The programme not only provided a sanctuary for creative exploration away from the distractions of daily life but also fostered an environment where I could collaborate with local schools and high schools, sharing my journey and research endeavours. Following my residency, the work I produced had the privilege of being showcased at various private events, including fairs, gallery exhibitions, and a public art centre. This experience forged lasting connections within a community of fellow artists and curators who share my passion for exploring themes such as diaspora, queerness, and post-capitalistic society, and with whom I continue to collaborate.”

Happily for Daniel and countless other emerging artists honing their practices here, Suprême NTM’s words today have a new resonance. ‘Chacun sa mafia, chacun sa mille-fa’.

@mo_laudi | www.fondationfiminco.com | www.komunuma.com

Photography by Ismaël Bazri, Aurélien Mole, Valentin Nguyen, Martin Argyroglo, Martin Perry and courtesy of Fondation Fiminco