It’s ironic that many who travel in the Deep South only skim its surface. Sure, there’s cuisine, music and southern hospitality to enjoy, but there’s also history. However, much of the storytelling begins with white American perspectives. Before them, Native Americans were the custodians of the land, but they were exiled and their culture extirpated in the 19th century. Lynn Houghton journeys to some of the most poignant sites on the Trail of Tears.

There are deer just ahead in the headlights of my RV. They stare brazenly at me as I lumber off the Natchez Trace Parkway at the point it leaves Tennessee and joins Route 11 in northeast Alabama. Unblinking, they size me up on approach, then quickly disperse. As dusk descends, the pink-hued sky turns a pale shade of magenta, then deep ruby and finally indigo. I roll into leafy Tuscumbia and decide to light a fire. Until the odour of burning wood overpowers it, the sultry smell of camellias wafts in the air.

I settle down to sleep but, by midnight, am aware of trains passing. They are probably within a mile of me, the low and loud moan of the horn making my bed reverberate. The Norfolk Southern Railway train is likely to be full of coal and industrial freight going to states further west. It was the first railroad on this side of the Appalachian Mountains and the original track was laid so goods and passengers could avoid the once treacherous Muscle Shoals of the Tennessee River. Sadly, hundreds of thousands of Native Americans didn’t have the luxury of riding this train when they were forced out of these parts and heading in the same direction.

I’m here in this part of the Deep South to find out more about the Trail of Tears. I am drawn here because my son from my first marriage is one-eighth Choctaw, inheriting the trademark high cheekbones and full lips of his ancestors, but with grey eyes like mine, rather than black like his grandfather’s. It’s fairly common knowledge that one of the most famous entertainers of the last century was also Choctaw. Born into an impoverished family in Tupelo, Mississippi, an ancestor of Elvis Presley’s was named Morning White Dove.

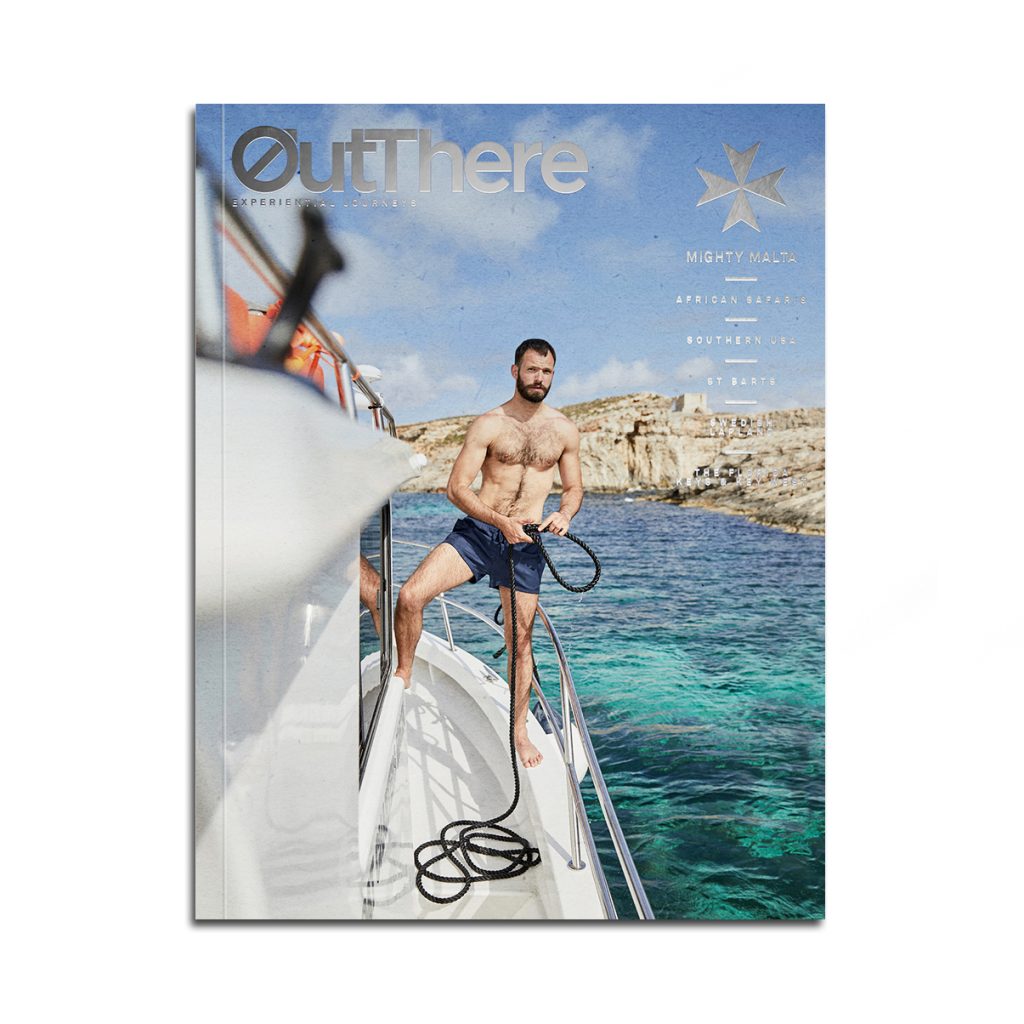

This story first appeared in The Mighty Malta Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

The Trail of Tears consists of more than 5,000 miles/8,000km of overland and water routes, along which a hundred thousand native people evicted from their homes in the southeast in the early 19th century travelled to the western frontier. In 1987 it was designated an historic monument by an Act of Congress and includes the main water route of the Mississippi, the Drane Route from Ross’s Landing on the Tennessee River, the Northern Route, and the Cherokee removal camps.

Initially, this ‘involuntary migration’ due to the compulsory acquisition of the land was to be agreed with individual tribes via treaties, but it ultimately turned into a forced removal by the US army. This was by decree of President Andrew Jackson and became known as the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Though most were evicted, those who stayed behind had their ancestral entitlement to land extinguished overnight. They had no choice but to be assimilated into white culture, giving up their traditions. The few who made this choice were stuck in limbo, ostracised by their own and despised by the settling whites.

I can attest that this event isn’t taught in schools in the USA. And, unless they have an ancestral connection, very few Americans will have heard of the Trail of Tears. Old-timers regale listeners with Civil War tales, often passed down from grandparents, but seldom do these storytellers say anything about the wholesale removal of the tribal people. Perhaps they are silenced by the shame. There are also those who may be ignorant. But many undoubtedly profited from the event and their descendants still live in the area today. They’d, sadly, be the last to tell you that the Indian Removal Act was unconstitutional, unorganised and miserably executed, cruelly leading to the deaths of as many as 15,000 people. Starvation, exhaustion and disease along these dogged marches heading west inevitably led to fatalities.

Monumental moves

On the banks of the Tennessee River is the site of a former pier that was a transportation hub for the beleaguered removal. Soon, it is to be developed into an ‘interpretive site’ by the National Park Service and the plan is to build an overlook here with views over the water, which Native Americans would have seen before leaving their homeland for ever. To have a closer look, I meet Sheffield mayor and resident Steve Stanley. We trek down to the water’s edge through the dense vivid green forest. It’s easy to spot evidence of a disused railway spur that was connected to the main station in the town and, initially, the carriages were drawn by horses. At one time, there was a three-storey terminal building here, but it was destroyed during the Civil War. Steve explains that archaeological evidence includes oyster shells, which indicate there was a seafood restaurant on this spot.

Steve is obviously moved when he tells me that Chilly McIntosh, a Creek chief, wrote from the new Indian Territory in Oklahoma to the citizens of Tuscumbia, thanking them for the unusually kind treatment his people received from them.

“The interpretive site here will be on the National Trail of Tears,” explains Steve, “but will eventually become a major part of the Singing River Trail, to be constructed all the way across northern Alabama to the Natchez Trace”.

Deep in this forest is another monument – the mile-long Florence Wichahpi Commemorative Stone Wall, which can also be reached from the Natchez Trace. An unmortared-stone structure that stands in honour of a local Yuchi woman named Te-lah-nay, the wall was assembled by her great-great-grandson Tom Hendrix in honour of his ancestor. Te-lah-nay’s people, the Yuchi, were one of the many tribes forcibly removed by the US army. The Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez were others – to name but a few – not to mention the Cherokee, who had land from here all the way to North Carolina. All became refugees.

It is said that Te-lah-nay’s presence can be sensed in this quiet place; her body may have been sent away, but her soul remained. After arriving in Oklahoma, Te-lah-nay was saddened when she realised that the rivers there didn’t ‘sing’ – in Yuchi folklore, rivers are homes to mythical sprites, who sing to soothe those who drown. That’s why they call the Tennessee ‘the Singing River’. I keep my ears open. I don’t hear any singing, but I feel Te-lah-nay’s pining for home.

The Cherokee Eternal Flame

In Chattanooga, Tennessee, I visit a few of the touristy sites, such as Ruby Falls, which I’m told was ‘first stumbled upon’ by prospector Lee Lambert when excavating in nearby Lookout Mountain. They still use words like these, as if it were white men who first founded everything and those who were here before hadn’t. But if, like me, you are to peel back the layers, you’ll find that perhaps this is a convenient way to avoid talking about the area’s scarred and dark past.

A fruitless journey

I head for The Passage, near the Tennessee Aquarium and on the Tennessee River. Chattanooga was formerly named Ross’s Landing, after Cherokee leader John Ross. A signpost displayed next to the river, not far from the Walnut Street Bridge, details the calamitous event. The Passage is an enormous installation: a weeping wall with mask-shaped artwork that represents the tears shed as the Cherokee were driven violently from their home. It is set alongside a staircase waterfall, which flows into the river.

John Ross, the leader of the tribe, was an educated man of significant political nous. In fact, by the early 19th century, the Cherokee had developed their own alphabet, even when they assimilated into white American culture.

In an attempt to save his homeland, Ross travelled to Washington DC to negotiate with President Andrew Jackson and dissuade him from enacting the legislation. Ross sadly failed in his mission and between the 6th and 17th June 1838, three detachments of his people were forced to leave from this very site. But by far one of the most significant staging areas for the native people’s removal was the confluence of the Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers at Blythe Ferry, not far from Chattanooga. This is the heart of the Cherokee ancestral land, and thousands would have camped here, hesitant to move. They lingered for weeks in squalid conditions, where disease was rife, only to be sent to their fates across the river on the Blythe Ferry.

This quiet, remote spot is the location of the Cherokee Removal Memorial Park at Blythe Ferry. When I arrive for my visit, the museum is unexpectedly closed, likely due to Covid issues, but outside are large granite monoliths erected and inscribed with the name of every single Cherokee person who was evicted from this area. I stand here completely alone, taking in the enormity, desperation and sadness of what took place. As I turn to leave, an eerie feeling comes over me, as if the essence of the people and their suffering were left behind.

Only half-an-hour’s drive from here, off Tennessee 317, is the Red Clay State Historic Park, formerly named Ela-wodi-yi or Red Earth Place. This lush, green park is now the site of an eternal flame in honour of those who lost their lives during the removal. I stand silently by the flame – as most visitors who come do – apologetic to those who perished during the removal. This was the last-ever meeting place of the Cherokee councils. The 263-acre park has a reconstruction of one of the council’s meeting houses and there is an extensive exhibition in the park’s headquarters of artifacts and the history of the area’s original inhabitants.

The Natchez Trace Parkway and Mississippi

“The Chickasaw camped at Pontotoc, near the Old Trace (Milepost 255) before being moved to Memphis,” explains Jane Marie Allen Farmer, a park ranger at the Natchez Trace Parkway Visitor Center in Tupelo. “On 4th July 1838, they headed across the Mississippi River westward to Oklahoma. Some travelled south along the Mississippi water route to the Arkansas River. They brought their family dogs, which were very important to tribal people. But the river boat captains would not allow animals on the steamers. So, the dogs swam and many drowned, desperately trying to follow their owners.”

I have now crossed the state of Tennessee. This parkway is part of the National Park Service and features signposts to point out natural features, such as the Jackson Falls, which tumble over fascinating limestone terrain. Some signposts commemorate historic events, such as Milepost 385.9, which marks the place where Merriwether Lewis – of the Lewis and Clark Expedition – met his mysterious death, either by murder or suicide.

Importantly, when entering neighbouring Mississippi, there is a placard commemorating the signing of the Treaty of Doak’s Stand. This is the place (Milepost 128.4) where the Choctaw ‘seceded’ much of their land to the US. Basically, these treaties were ploys to steal property that officials knew rightfully belonged to the original settlers: gunboat diplomacy at its worst.

The road now weaves its way down through once-mysterious and nearly impenetrable swamps and marshes of the state of Mississippi. Large herbivores – bison, possibly even woolly mammoths – used this higher ground to navigate over swamps and marshes. Native people, thought to have arrived from a land bridge that connected Alaska with Asia about 12,000 years ago, followed the animals on the hunt and eventually settled here, happily. That was until the Europeans arrived in the 16th century and sealed their fate.

The Choctaw, along with the Chickasaw and Natchez, originally owned well over five million acres of land in Mississippi. The evidence of a rich culture still abounds, as they built enormous burial mounds (one measures 13 acres across the top). They also created utensils from stone, jewellery from marine shell, clay pottery, copper art and invented ball games that emulated war to avoid actual conflict.

It was the Native Americans who called the river ‘Mich sha Suppukui’, which is pronounced ‘Mish-sha-sippi’ and translates to ‘river beyond any age’. The mighty river was to them sacred.

Poignantly, this was one of the main water routes on the Trail of Tears. It’s deeply ironic that the Mississippi River, with its significance for native peoples, was used to remove them from their home. I paddle the ancient river in a canoe, its vastness and beauty filling me with awe. But I can’t help but feel deep grief for my son’s ancestors, who were forced to take a one-way journey on this huge river artery, feeling lost in their own land and suffering from persecution, hatred and death as a result. Their souls haunt this wide river and if the sprites were to sing here, they’d be wailing.

I am ashamed of this time in American history. And, while there is nothing I can do to fix it, I recognise that it still bears enormous consequences for the descendants of Native Americans.

It will be good if the whole thing is spoken about more. It needs to come to the fore rather than being swept under the proverbial rug. Though it may be too little too late, the Federal recognition of the Trail of Tears routes, with signage unapologetically and squarely placing the blame on the Federal government of the time, is seen as an apology in all but name by much of the tribal community. Coming along the trail is a way for many to learn about it, reconcile a difficult past and take home with them some important lessons for the future.

Photography by Zeke Tucker, Chad Madden, Tim Barber/Chattanooga Times Free Press, Jed DeKalb/State of Tennessee, Rodney Truitt Jr, Art Meripol, Lynn Houghton, Justin Wilkens, Ronnie Mayo, Ronny Sison

Get out there

Do…

… check out the 230-mile/370km Trail of Tears Commemorative Motorcycle Ride, which takes place on the third Saturday of September. It was started by two friends, Jerry Davis and Bill Cason, and is now officially recognised and signposted.

… visit the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park in Georgia, which is celebrating its 120th anniversary. It’s just 10 miles/16km from Lookout Mountain.

… have a paddle on the Mississippi River with the Quapaw Canoe Company, which offers day trips, multi-day trips or extended expeditions that include travel by canoe, kayak or paddleboard, as well as camping out on river-island beaches.

Don’t…

… forget to take a look around the B B King Museum in Indianola, Mississippi, and find out more about this Blues legend, maestro and the guitars he called Lucille. Plus, they serve fantastic tamales just next door.

… miss the Audubon Acres nature reserve with four miles/6.5km of hiking trails. There’s also the Spring Frog Cabin built in the 18th century using native construction techniques and Little Owl Village, a Napochie Indian site with the remains of a late prehistoric or early-historic circular winter house.

… overlook Magnolia Grill in the Under-the-Hill district of Natchez, Mississippi. Its jumbo gulf shrimp atop cheesy grits and crawfish étouffée are superb.

The inside track

Cynthia Wood and Antonia Poland, the owners of Davis Wayne’s in Ooltewah, Tennessee, named the restaurant after their fathers. Inclusion and diversity are the focus here, but it’s about great soul food too. The couple also have a catering business, Dipped Fresh.

Eat

Kermit’s Outlaw Kitchen in Tupelo, Mississippi (the birthplace of Elvis Presley), is all about southern cuisine and local farm produce. Try the smoked wings, loaded fries and edamame bowl.

Drink

The fabulous Easy Bistro & Bar in Chattanooga has a delightful raw menu with oysters aplenty. But the bar is equally charming, with cocktails, fine wines and over 300 whiskies to accompany its dishes.

Chill

The Bluff View Art District at 411 East Second Street in Chattanooga is a great place to eat and enjoy spectacular views. Be sure to pop into the River Gallery while you’re there.