Until the CCK opened there wasn’t a national museum of contemporary art in the city and the galleries and museums were all privately owned, so Argentina’s art scene flourished outside of the nation’s capital. Guido tells me that, until recently, there just wasn’t much government support for the arts here, so both the cities of Cordoba and Rosario had and continue to have strong arts scenes.

“Across Argentina, we’ve always had a very strong tradition of art – particularly painting – and that is still very much alive… But in a way, we are in the shadow of the 80s and 90s when Argentina produced some really great artists. It was a moment of revolution and their work reflected that. Now the consensus is that we are in much more ‘flat’ times. It’s not easy to be seen as a rebel now and make shocking, attention-grabbing art. So the work of younger artists are a little more encrypted. There are also so many more influences on young artists, due to the internet and social media – so there is no longer an excuse to be naive. We are all so exposed to the systems that control the world, from the stock markets to corporations, from the environment and world politics; and that knowledge means you can no longer be sat alone in a room making purely introspective art. Artists today need to do work that acknowledges this connection with the world, that deals in some way with all that knowledge. With that comes subtlety and nuance, it’s not so easy to make sweeping statements and the weight of that bears down on us, no longer will simple statements suffice in an ever more complex and interconnected world.”

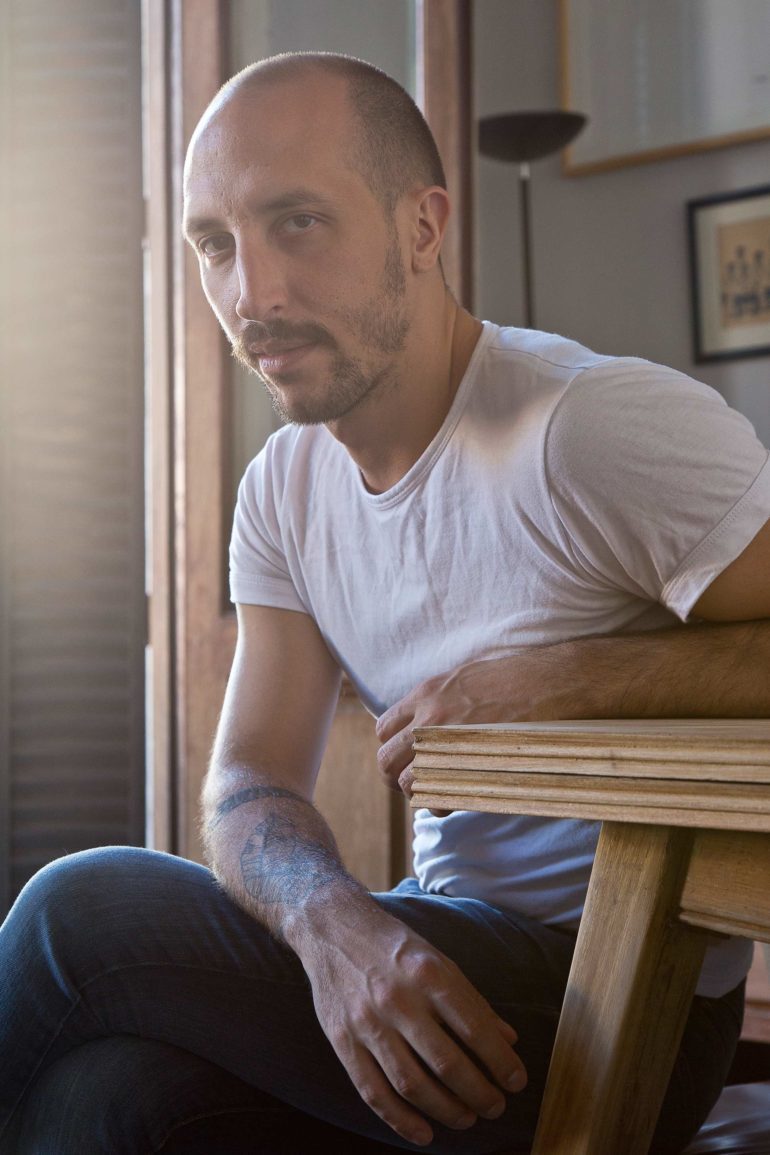

The movement by young Argentine artists to reclaim and redefine their work was another important factor in Guido’s career. In 2010, he teamed up with five other young, gay men involved in art to form Sauna, an online magazine that takes a fresh look at the contemporary art scene.

“As my work is by its nature ephemeral, I write about it as a way of recording and understanding it. I write about the processes.” Which is how he met his partner Marcelo. “We had friends in common (all of us were gay and all involved and interested in the contemporary art world). Newspapers talked about art in a way that is basically just descriptive and unchallenging, whereas academic journals on art were inaccessible and dry. We all felt there needed to be an independent voice that filled the void. So we decided to create Sauna. The title was intended to be tongue-in-cheek. We liked the double meaning – a sauna being a place of introspection and meditation, but also synonymous with gay culture. We played with that and all six of us even posed naked for a photo-shoot for our anniversary issue. Sauna was quite a success in that people liked the way that we presented contemporary art in an entertaining but challenging way – and we became quite well known on both the art and the gay scenes.”

From my limited experience, despite the importance of Catholicism in Argentina, being openly gay in Buenos Aires seems to be totally acceptable, something which Guido confirms.

“I never hide my sexuality and to be honest, it’s just really not an issue for me, Marcelo or anyone. It’s very cool to live your life as yourself here. The art world is especially open-minded, I’ve always been out in the art world, right from my earliest days as a gay teenager working in the museums. That’s why I didn’t ever feel the need to tackle it as an explicit theme in my work. But I think that there’s a little bit of it in everything that I make. I also think that Marcelo and I are kind of a statement in our own lives. We live together openly as a couple and have two teenage kids, 19 and 15 (Marcelo is their biological father). At their school, I am known as their other father and we have been interviewed by magazines as a ‘modern family’. So I think we make our statement in being open and not hiding who we are. Our kids also teach us to be free as they have no hang-ups about anything, they are amazing.”

It’s truly heartening to hear this, especially at a time when in other places in the world, the tide seems in danger of turning quite dramatically away from liberalism and towards a worrying, hyper-moralising and reactionary form of neo-conservatism. And perhaps Argentina will once again become the sanctuary to those fleeing oppression as it did for the large Italian community at the turn of the last century. But that remains to be seen. The one thing that is certain however, is that the freedoms that Guido and his contemporaries enjoy will never be given up without a fight.

“We have a very strong tradition of activism and people aren’t scared to put themselves on the line for what they believe. I think this is why we have made so many advances in gay rights, marriage equality, and gender politics. But saying that, there is still a divide between Buenos Aires and the rest of the country and that is something that needs to be addressed through education. Interestingly there are more trans* people in the interior of the country than here, but they are much more marginalised.”

So what does the future hold for Guido? He continues to push his boundaries, with his writing and performance art. He looks forward to an exhibition in Hamburg, Germany which is made up of ‘light paintings’ – projected light and wooden structures.

As I leave the sanctuary of his cosy home and head back into the bustling streets, I feel happy to have met yet another inspiring, creative, switched-on and sorted gay man, part of our global community. Guido is the best the kind of role model. The kind of person you want all your friends to meet, so they can share in his illuminating company, but also one to present to those anti-gay bigots, to watch his easy charm melt their prejudices away.

Find out more about Guido’s work at www.guidoignatti.com.ar and Sauna magazine at www.revistasauna.com.ar.

To get a sense of today’s Argentine art scene, visit Guido’s workplace, the enormous Centro Cultural Néstor Kirchner (CCK), one of the largest art centres in the world and also the largest in Latin America.

Photography by Martin Perry, Sebastian Freire and Wes Magyar