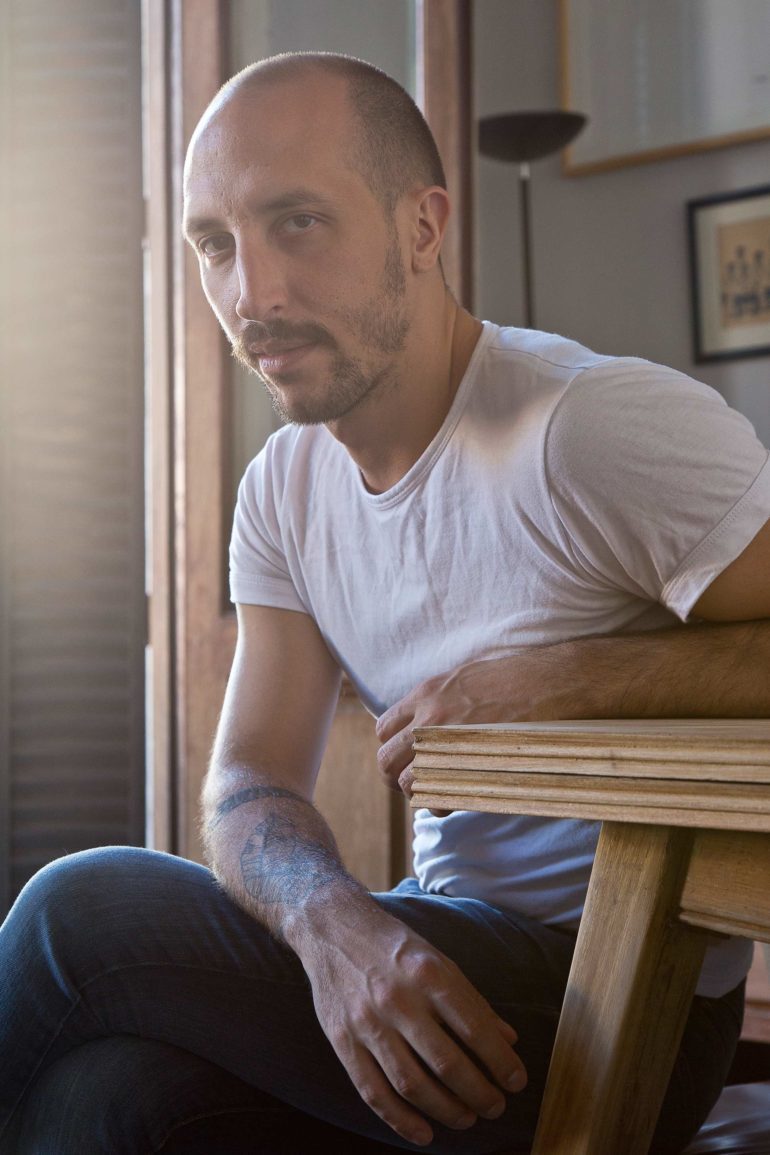

Internationally acclaimed Argentine artist Guido Ignatti shares his thoughts on life, work, country and sauna.

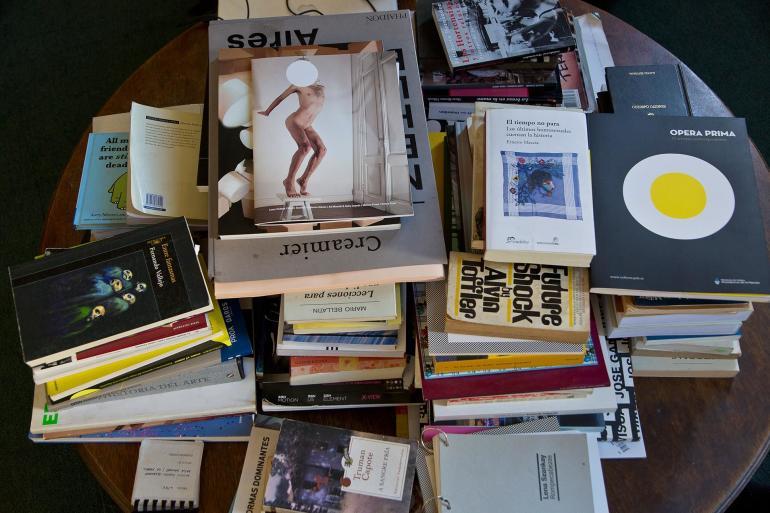

Guido Ignatti’s home is the kind of place that makes you feel instantly relaxed; it reflects his easy-going, chilled persona and is filled with individuality. His beautifully presented, eclectic and humorous art collection adorns the walls and just about every surface. Coffee tables and shelves are chock-full of books and journals – everything from the Argentine literary hero, Borges, to Ernesto Meccia’s socio-narrative El tiempo no para, a novel about how life has transformed for gay men in Buenos Aires, to Monsen and John’s cartoon dinosaur cover of All my friends are dead. A big, ginger cat sits lazily on a well-worn cushion on an old wooden chair. Everything about the place exudes a laid-back, intelligent, life-loving personality. It has clearly been put together by someone with a creative eye for detail, but not for even a second does it feel contrived.

Guido makes tea and brings it in on a tray, just like the way my grandmother used to, complete with mismatched cups and a selection of treats, although his are of a far more healthy variety – I’m ready to move in. It is very much a living space – he shares it with his writer partner, Marcelo, and their two teenage children (and the cat, of course). It also serves as his design studio where he plays with his ideas, before creating his signature, site-specific installations in a variety of locations from California to Hamburg; and of course his native Buenos Aires.

Born to a working-class family on the southern outskirts of Buenos Aires, Guido loved art from a young age.

“I’ve always painted and drawn. At high school, I studied commercial art and although I wanted to be a fine artist, I was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to make a living, so I spent 2 years at the Teatro Colón, studying and working with all aspects of theatre design and production – set design, make-up, wigs, wardrobe and the like.”

Guido is a product of Argentina’s enlightened free-education system that allows access to higher education regardless of family income. He studied sculpture at university, leading him to jobs at museums and private galleries, which in the early Noughties were undergoing a boom in popularity. The low value of the post-economic-crisis Peso, combined with a large amount of great Argentine artists, attracted a lot of foreign art collectors.

“It was a great time to be involved and gave me a very good grounding in how the art world works. But after a while, the bubble burst and I witnessed first hand the ruthless way that artists were used and abused by the art system. It put me off making art for a couple of years. I had seen how artists were treated and I was shocked.”

He reassessed the validity of producing ‘saleable art objects’, thinking about his work differently. He moved to making site-specific work, projects that happened at set times and places. This direction proved to be a rich vein, especially in a city that allows for the possibilities of using unusual and otherwise unused spaces to create art in.

This story first appeared in The Inspirational Argentina Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

“Many artists are creating work in buildings that are due to be torn down and redeveloped. Developers are open to these projects.” This is a rarity in other capital cities around the world, possibly because Argentines don’t have a litigious culture. In the States, for example, everyone is scared of being sued should anything happen, but in Argentina, they aren’t. This breeds an atmosphere of freedom and opens up all kinds of possibilities which otherwise would be shut down due to red tape.

I’d experienced something of this freedom the previous night. I was invited to a tiny restaurant in Palermo which had just been turned into an impromptu club, made all the more enjoyable by a spectacular set by a Burning Man DJ. The place was filled with attitude-free, convivial locals of all ages and persuasion – dancing, drinking and laughing; in so many ways reminding me of the party nights we used to throw in London in the 90s, where the only prerequisite for entry was that you checked any attitude, along with your coat, at the door. This was a time when London was generally much less segregated, when you could just as easily get chatting to a girl from the local council estate as you could an investment banker – gay, straight, black, white, Asian, Latin – it genuinely didn’t make a difference. As long as you were in the right frame of mind and loved the atmosphere and the music, we were all as valid and welcome as one another. It was a time before crippling health and safety regulations prevented young people from setting up camp and expressing themselves in otherwise abandoned buildings and spaces and a time before everyone spent the night on their smartphones. We were there in the present, enjoying each other’s company without fear of the rest of the world seeing what we were getting up to at 4am on a Saturday morning.

I’m not by any means suggesting that Argentina is some kind of cultural backwater, or stuck in the past. But because of the decade of economic restrictions imposed upon the country, combined with a fiercely independent attitude and temperament, the country – or at least Buenos Aires – has preserved a sense of freedom and lack of restriction. It’s like Berlin, but without being overly pretentious, or Barcelona with far less commercialism. The creative scene also seems informed by a plethora of historical, ‘old world’, yet international influences – and just like how they serve sushi with cream cheese here – it is fused with a bit of Latin flavour.

Buenos Aires in particular is also undergoing a renaissance in its art world. The previous government had put a substantial amount of money into creating a museum of modern art, the Centro Cultural Néstor Kirchnerwhere Guido works as an exhibition designer. Housed in what used to be the main post office of the city, it is an entire street block in the port area, with over nine floors – enclosing a courtyard and a great vantage point to view the city. According to Guido, the building was closed for nearly 20 years and the Kirchner administration pushed hard for it to be turned into a cultural centre. They made it a huge priority right at the end of their tenure, probably so they could name it ‘Kirchner’, but this made everything a bit rushed and it opened unfinished. The new administration then closed it down and set to work to finish off the building; it finally re-opened, fully functional in May 2016. There are 25 permanent exhibition spaces in the building, with two of the bigger spaces dedicated to large-scale, site-specific installations. But it’s not just visual art, the cultural center comprises of symphonic music, popular music, and contemporary art. Furthermore, it is government-funded and completely free to the public.