Palma’s position as the cultural capital of the Balearics is brought vividly to life on an exclusive private tour of its many museums and galleries. Alongside works by key Spanish painters and contemporary masterpieces, tales of keeping up with the Joneses and blatant attention-grabbing abound.

Standing in the magnificent ode to Spanish modernism, the Pilar i Joan Miró Foundation in Palma, we are debating whether the alabaster ‘windows’ that architect Rafael Moneo used for the building were intended to keep the ugliness of the world out or the beauty of the 6,000-piece Miró collection in.

‘We’, in case you’re wondering, are myself and my new friend Nicole, the delightful guide from the Castell Son Claret hotel. I’m acting as her guinea-pig on her new art tour of Palma, a somewhat bold, experiential addition to the capital’s buzzing art scene. The property is keen to showcase the very best that the island has to offer by way of authentic experiences, from food to mountain-biking and – in one instance – the two combined.

Mallorca isn’t a destination that really markets itself as arty but, I’m told, it was here that Miró created the sun icon that the Spanish Tourist Board still uses as its internationally recognised logo, not to mention that of the island’s own tourism organisation, one of the oldest in the world. Compounding this claim to fame, the island offers many internationally renowned events – from the Art Palma Brunch in March, to the Art Basel-organised ArtMallorca in September and the Nit de l’Art celebration that runs at the same time.

Nicole regales me with her wisdom about Palma’s art scene. Not only is she an expert on its cultural offerings, she’s also a passionate, adopted Mallorcan, like Miró himself. Originally from Paris, she came here over 50 years ago at the age of 19, met her life-partner on her first night in town and never left.

She and I conclude that, in any case, the foundation’s main building – in fact, the whole Miró ensemble here – is a mishmash of architectural styles, colours and quirkiness. The ensemble consists of the Josep Lluís Sert-designed studio El Taller Sert, where Miró worked, the rustic Son Boter farmhouse, the artist’s own playground (with his original, genius-borderline-madman wall-scrawlings etched in time like Neolithic cave drawings), and his private residence Son Abrines, where he’d often answer the door to Miró fans seeking him out, dressed in dirty overalls and pretending to be the caretaker.

This story first appeared in The Magnificent Mallorca Issue available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

But it’s when you factor in the foundation’s location overlooking the sea on the outskirts of Palma that this architectural ensemble becomes a piece of art in itself – perhaps even Miró’s finest legacy. And the work that he produced here was different from that he made in Barcelona. In my humble opinion, Mallorcan Miró was more imaginative, metaphorical and certainly more convention-defying.

Nicole informs me that the islanders have always defied the norm where culture’s concerned. For example, some of Miró’s politically charged work put him in a precarious position during Franco’s reign, but that didn’t stop the infamous Galería Pelaires (Spain’s longest-running contemporary-art gallery) from putting on an exhibition of it at that time, along with many other works that raised the eyebrows of the authorities. The gallery continues to push boundaries to this day, with exhibitions of acclaimed local and international artists, whose work I find satisfyingly incongruous with the historic Old Town space they’re displayed in.

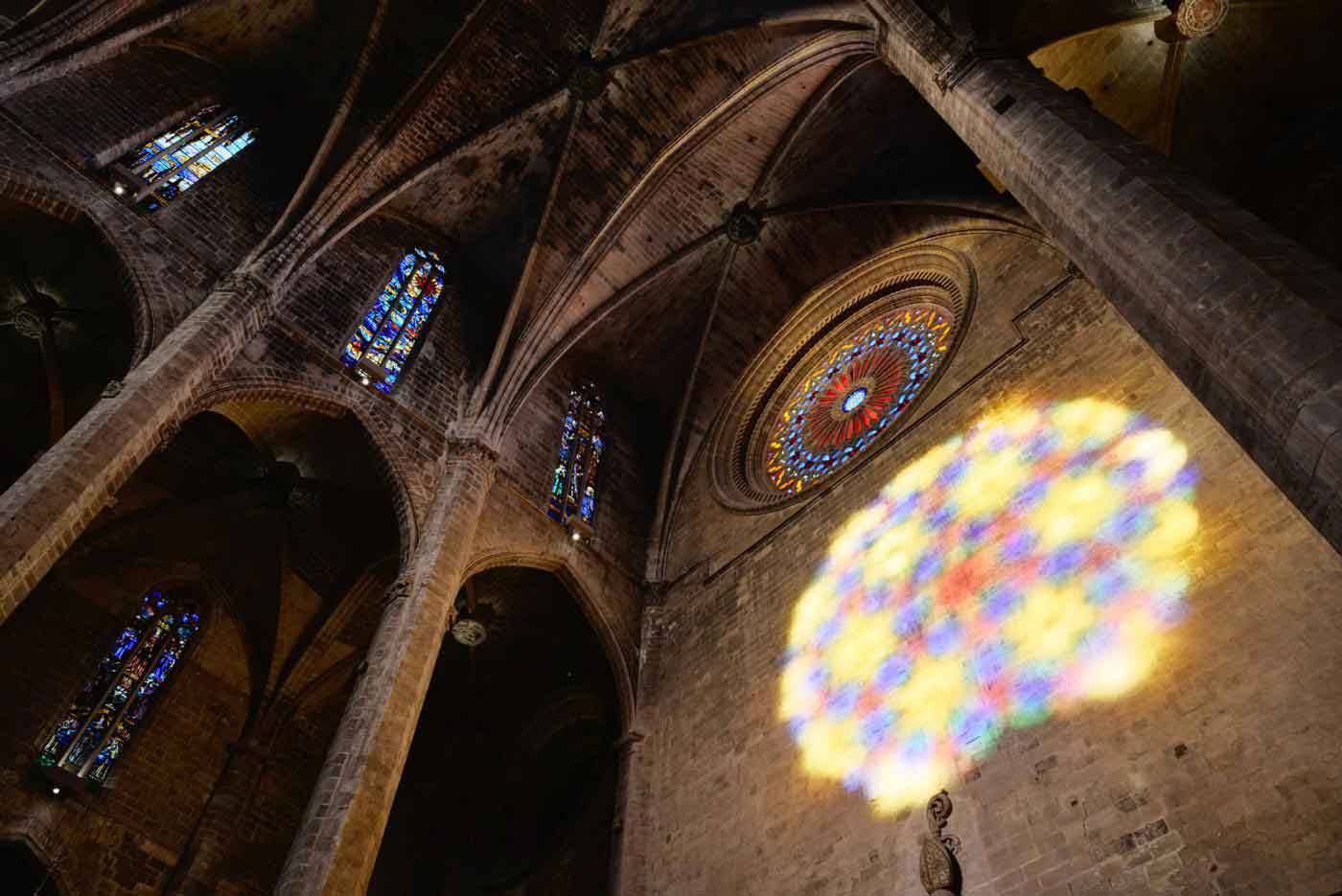

To get a handle on this pushing of the cultural envelope, Nicole wants me to step back much further in time. Our first stop is the cathedral – odd perhaps on an art tour – but wholly relevant. It’s the island’s most-visited tourist attraction and also an example of how, even in the deepest pits of Christianity, art prevailed. Three bishops made their mark on the building – the first installed the huge 14m-wide, stained-glass rose window, the largest in Gothic architecture anywhere in the world. The second commissioned some signature Gaudí embellishments. The third allowed acclaimed conceptual artist Miquel Barceló to create a jaw-dropping, love-it-or-hate-it installation of the miracle of the bread and the fishes in the cathedral’s most prominent apse.

It seems that the desire to grab attention has much to do with the long history of art here in Palma. Despite Mallorca’s cosmopolitan vibe and considerable wealth, it was always considered a back-water of Spain. So, like the bishops, many of the island’s merchants and noblemen did all they could to keep up with the Joneses.