Returning to Florence for a lesson in how many of the city’s (and therefore, the world’s) most revered artists have had to navigate producing art for the Church while being queer, Zack Cahill flips through the pages of history: what he finds is a story of perseverance – and cheek.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that post the recent global catastrophe that shan’t be named, travel went right back to the old days, the height of cheap flights and frivolous getaways. But that’s not quite the case. Habits have shifted, and values have, too. At least that’s what The Luminaire, a brand-new luxury tour operator with a crystal clear aim to make ‘intellectual travel cool’, is banking on.

And maybe it’s cool already. An increasing number of people are citing unique learning experiences as a reason to travel that’s more alluring than nice spas and swimming pools.

I love a nice spa, but I’d say I’m in The Luminaire’s target market. Maybe it’s because I often visit places with the intention to write about them, but I’ve always found trips where I’ve learned something new far superior to those where I laid on a beach getting hammered for a week.

This is why I find myself on a hotel roof overlooking Florence with Kevin Childs, a writer and lecturer on art history and the history of visual culture. Kevin is very interested in the contribution to culture made by LGBTQ+ people throughout history. So I’m ready to see Italy, and more specifically Florence, through a very specific, queer lens.

And in Florence, queerness really is inescapable. This is a city where two out of three men were accused of sodomy and a city whose greatest artists were (to quote Kevin) ‘massive queers’. A city where – much like in Victorian England – queerness was publicly condemned while being practiced with relish behind closed doors.

This story first appeared in The Sublime South Australia Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

Kevin is droll with a musketeer’s beard and dripping with adornments: rings, necklaces, scarves. It’s the golden hour, the last rays of sun glinting off the spires and domes of what was once the gayest city in the world (not a real statistic) and Kevin is giving a potted history in his softly arch tones.

The gist of it is this: whilst homosexuality was technically illegal, the majority of Florence’s greatest artists (and therefore arguably history’s greatest artists) were not straight. So whilst something had to be seen to be done, and there was great pressure from powerful people within the Catholic church (particularly the fire and brimstone preacher and ascetic Girolamo Savonarola) there was a tension there. They didn’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

So the ‘Office of the Night’ was assembled – it’s a suitably nefarious name for a magistracy created to find and prosecute Florentine ‘sodomites’. Responding to anonymous tips posted in church letterboxes, they aimed to restore morality in the city. Just how effective they were, or even aimed to be, is up for debate.

Want to know if a sculptor was gay? Say it with me: ‘contrapposto’. It’s a particular stance, you know it when you see it, and you’ll see a lot of it in Florence. The hip thrust out to one side, the majority of the weight placed on one foot, the opposing leg gently flexed, and the heel lifted. It feels instantly androgynous, these hulking figures equipped with a pseudo-feminine look, a softening of their body language. Think of Michelangelo’s David. His body is the Apollonian ideal, evoking the perfect physiques of Greek antiquity with which the Florentines were obsessed. And yet his posture is soft, gentle even.

Michelangelo: gay.

Now, look at Neptune by Bartolomeo Amanatti. Google him. He’s bigger than David, He hasn’t skipped leg day. But more than this, his stance is unmistakably masculine. He’s blockier, harder. It’s not just that Amanatti was a less accomplished sculptor than Michelangelo (everyone was, after all), it’s that Amanatti was not seeking to imbue him with that same androgyny, that softness.

Amanatti: straight.

I’m not saying the system is infallible but it’s near enough.

“I have to profess some ignorance here. Last time I visited Florence I saw the replica of Michelangelo’s David that stands in pride of place here and made an unconscious assumption that all the other sculptures were reproductions, too. Not true”

But tonight as we wander down to Piazza della Signoria in the heart of Florence, the oh-so-straight Neptune looks a little less so, with his buttocks lit up in pink in celebration of gay pride. He cuts a strange figure, hulking over us in his fountain like an NFL linebacker with the glowering face of Cosimo de Medici.

Ah, those slippery Medicis, as ever, are at the heart of all this. It was Cosimo who started it all. A rich banker who leveraged his money into power and became the most influential patron of the arts of all time, bankrolling Michelangelo, Donatello, and all the Ninja Turtles.

For now, we wander the square before entering the Uffizi. And I have to profess some ignorance here. Last time I visited Florence I saw the replica of Michelangelo’s David that stands in pride of place here and made an unconscious assumption that all the other sculptures were reproductions, too. Not true. It feels almost obscene to be able to come so close to them: Cellini’s Perseus with all its George Romero blood and guts. Giambologna’s Abduction of a Sabine Woman – these are the real deal. The touch of the artist’s hand preserved for 600 years, out here in the elements next to herds of tourists and guys trying to sell you knock-off iPhone cases.

Inside the Uffizi gallery, so named for the offices (‘uffizi’) of the Cosimo administration, the scene is different. The building, one of the finest in Florence, was designed by Georgio Vasari, who wrote a tome called ‘Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects’ – a ‘great resource’, says Kevin. ‘And he was a great architect himself. Not a great painter though. And a terrible bore… everyone hated him’.

Kevin’s jewellery sets off the metal detector but we’re quickly waved in.

There’s a scene in The Agony and the Ecstasy, the novel-turned-film about Michelangelo painting the Sistine Chapel, where Rex Harrison’s Pope inspects the master’s work in progress and raises concerns about all the male nudity.

Michelangelo, played by Charlton Heston at his most commanding, replies in his grizzled Illinois accent; ‘I believe God made Adam in his own image. Should I improve upon it and put him in britches?’.

Kevin’s tour focuses on the tension in these paintings between the religious conservatism of the church, which commissioned much of this work, and the well-documented queerness of the artists who produced it.

This is captured perfectly in Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo. The image – Michelangelo’s only finished panel painting – depicts Jesus, Mary and Joseph, prostrate against each other on the grass, with John the Baptist lurking just behind them. But behind him, and completely unrelated to the foreground figures, are a bunch of naked men bathing in a lake. Why? ‘Well presumably because Michelangelo thought they looked good’, says Kevin. ‘For me, this is the only example in western art where the intended religious message of the subject is entirely undermined by the background’.

Galleries are places of fascination and overwhelm. Without context, they become a blur. This is why it’s so helpful to have Kevin here with his laser-focused theme of sex and depravity.

Here’s Caravaggio’s painting of Bacchus, tugging suggestively at his robe as he invites the viewer in for wine. ‘A real bad boy, Caravaggio’, says Kevin. ‘He’d shag anything that moved’.

And here’s Carracci’s Venus with a Satyr and Two Cupids, in which Venus herself looks unmistakably male from the back. When you know what to look for, it’s everywhere. It’s contrapposto a-go-go.

Leaving the Uffuzi after dark, we wander towards the Via Pellicceria, where furs were once sold and men prowled for ‘birds’ (young men). The Ponte Vecchio too was a hotbed of illicit sex. In just one butcher shop, six brothers were prosecuted. There were threats that they’d be burnt down or fined, though neither ever happened, and it generally rarely did.

Sexuality was a different beast 500 years ago. They didn’t have a word for homosexuality, and if they’d had one, many of the men in question would not have identified as such. It was simply the way of things.

Florentine men became sexually active around 14 but didn’t marry until their thirties. In between, most of them filled their time with sodomy. It seems to have been taken for granted as long as their behaviour wasn’t flaunted and one rule was adhered to – that the receptive or ‘passive’ partner be a youth, younger than 20, and the active partner should be older, nearer thirty. This, they believed, was the natural order of things. Any deviation from the rule simply wasn’t cricket.

“Indeed, I am allowed to actually turn the page and see with my own eyes, the name Michelangelo written in pen and ink by some Office of the Night functionary 500 years ago to mark an accusation of buggery.”

Over a delicious Italian meal in some tucked-away tavern, I wonder how successful the Office of the Night actually was at quelling all this rapacious buggery. The answer is not very. In a city of 40,000 people, as many as 17,000 were incriminated at least once, but only 60 were imprisoned, exiled or punished.

The problem was that the highest profile people in the city, from Medicis to Martellis, families with schools and plazas named after them, were at it, too.

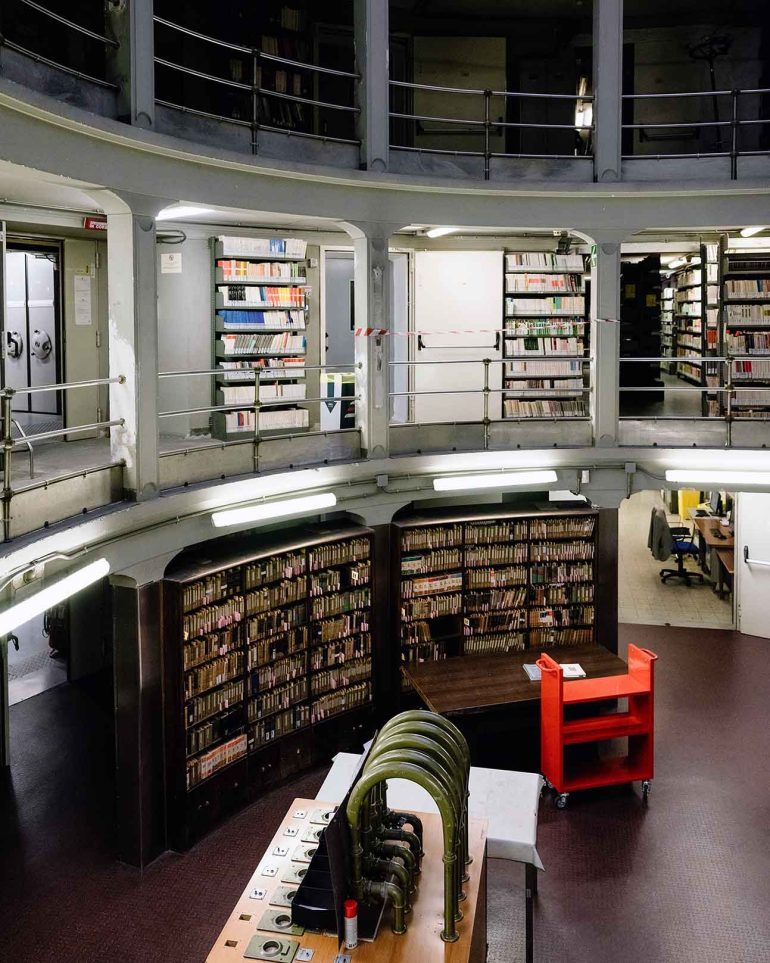

I know because I’ve seen their names, alongside Michelangelo’s and Leonardo’s, in the Florence State Archives. It’s here that the access and expertise provided by The Luminaire come into their own.

In a small room inside a dusty government building, we meet Doctors Fabio D’Angelo and Francesca Fiori for a look at the legal documents the office kept.

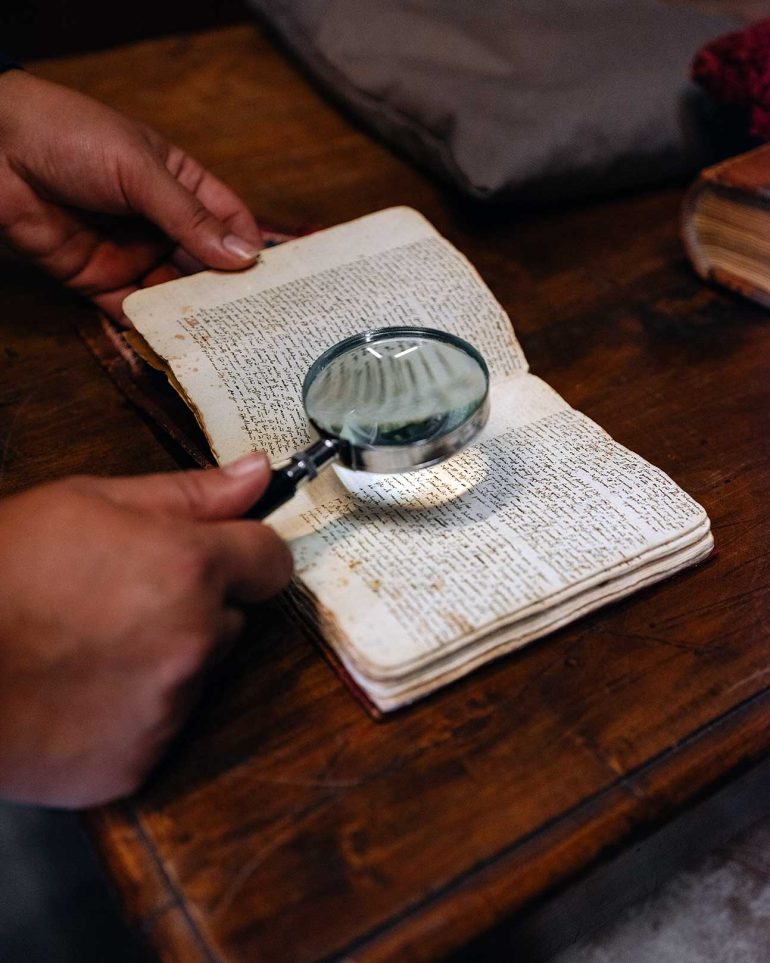

I see the documents as soon as I enter the room, piled high, faded and frayed, bound loosely by white ribbons, thousand-page teetering tomes, just sitting there. No glass screen separates me from them, and no stuffy, white-gloved guardian forces me to keep my distance. Indeed, I am allowed to actually turn the page and see with my own eyes, the name Michelangelo written in pen and ink by some Office of the Night functionary 500 years ago to mark an accusation of buggery.

It’s absolutely astounding. The doctors talk animatedly about these documents and their significance but a lot of it washes over me as I just stare at them transfixed. I imagine the people that wrote them, what they wore, and what kind of lives they lived.

But if society at large was so quietly permissive, and the fines and punishments so rarely followed through upon, why were they even bothering? Of course, there was a huge element of keeping up appearances. But at least some powerful people in Florentine society were true believers. Not least Savonarola, the fire and brimstone preacher who condemned sodomy from the pulpit. In the National Library of Florence, I see the sermons up close, in Savonarola’s own microscopic handwriting. I’d like to think he scribbled these, spittle spraying the parchment, hunched over a desk by candlelight in a blind fury while outside his window, artists prowled around the Florentine night.

On our final day, Kevin brings us to the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, home of Donatello’s David. The sculpture isn’t as famous as Michelangelo’s version, and the two make an interesting contrast.

Donatello’s is younger, and less buff. Delicate and dainty, even. This David was the first full-scale near-nude sculpted since Greek antiquity, a grandad to the other nudes we’ve seen. ‘They’re made to be walked around’, says Kevin. ‘And when you do, you’ll see all sorts of details. David’s extremely feminine bum, the wings of Goliath’s helmet caressing his leg and David’s toes curled into his beard. It’s all very sensuous’.

Joining us this morning is Ludovica Nicolai, who restored the statue over the course of a year. Via her son, who acts as a translator, she explains how she used porcupine quills to remove dirt and restore the statue to its original glory. Modern imaging even allowed them to find one of Donatello’s own fingerprints, preserved in the statue for 600 years.

Afterwards, we take in a few more spectacular nudes up close.

There’s Michelangelo’s Bacchus, pissed as usual, and not as ripped as David by a long shot (more gym and less wine needed there).

Kevin’s engaging narration carries us around on a river of anecdotes, observations, and historical points of interest.

We pause at a sculpture of Narcissus by Cellini.

‘In the story, Narcissus was actually in love with another man, not himself’, says Kevin. ‘When he died he turned into a flower. So in a way, it’s a positive story of homoerotic love. But that’s not the story we all know. In the end, they found it easier to talk about self-love than homosexuality’. Alas.

The Luminaire has co-curated a journey to Florence with art historian Kevin Childs. Over four days (three nights), guests will explore Florence’s world-class art collections within the context of Kevin’s expert insight, tracing an enthralling queer narrative through the city’s richly frescoed palazzi. From the Uffizi Gallery and Palazzo Vecchio to the Bargello National Museum and a banquet dinner at a private Palazzo, the journey is an in-depth exploration of Florence’s unorthodox past. The journey includes accommodation at five-starred Villa Cora, all experiences with Kevin Childs, and the banquet dinner at a private Palazzo. Excludes flights and other meals.

Photography by Tessa Chung, courtesy of The Luminaire and via Unsplash

Get out there

Do…

… allow ample time to explore Florence. It may feel like a destination for a two-night city break, but if you want to drink in the full experience, you’ll need more time.

… go armed with a plan of what you want to see. Florence contains an overwhelming amount of art, history and art history. If you want more than just a checklist of standard photo ops to breeze by, do a little research before you go. Or – the best option – find yourself an expert guide.

… book priority entry to the big museums if you’re travelling in high season. The Uffizi Gallery in particular fills up and books out fast, so it’s essential to plan well ahead.

Don’t…

… forget to check out the more bohemian south side of the river. Most of the popular tourist sites are north of the Arno, but the south side – Oltrarno, as it’s known – is quirkier and more relaxed.

… eat in the main plazas. Those tourist-trap restaurants don’t need repeat business. Wander down a side street. If it’s narrow and rammed full of stylish locals, it’s a safe bet. And once you’ve had your fill, make sure to pop into Gelateria La Carraia in Santa Croce.

… commit a clothing faux pas when visiting the churches. Cover your shoulders and take off your hat. Yes, it’s conservative, but what do you expect – they’re churches.

The inside track

As chief executive and co-founder of The Luminaire travel company, Adam Sebba seeks to help curious and discerning travellers cultivate a deeper understanding of the world by designing unique experiences with them in mind.

Visit

Tucked away in the hills, the Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio keeps precious traditions of silk fabric-weaving alive. It collaborates with top fashion houses to design bespoke fabrics, and seeing them being made on the original handlooms in the workshop is fascinating.

Escape the crowds

Museo Stibbert is a lesser-known museum with a private collection of armoury, textiles, ceramics and other objects assembled by Frederick Stibbert. The gardens are by Giuseppe Poggi, who was responsible for much of the 19th-century re-modelling of Florence.

Eat

I love the Osteria dell’Enoteca. It’s set in a modern space within an ancient townhouse in Oltrarno, one of Florence’s coolest neighbourhoods, and the food reflects that – it’s old-style Tuscan cooking with a modern twist. My tip is to request a table at the back, through the wine cellar.