At first glance, the gracious palazzos, labyrinthine streets and winding waterways that made ‘La Serenissima’ the world’s first city-scale immersive art exhibit bewitch just as they have for centuries. But Uwern Jong soon discovers a new, homegrown creative energy that’s remaking the character of ancient Venice.

I’ve been beguiled by Venice ever since watching director Nicolas Roeg’s classic 1973 movie Don’t Look Now. In its opening sequence, the camera glides under stone bridges through the city’s mist-shrouded canals, weaving between gondolas’ lantern lights and the crumbling façades of centuries-old palazzos, evoking a haunting, otherworldly atmosphere. Anthony B Richmond’s masterful cinematography captures Venice in all its enigmatic glory, its meandering waterways and labyrinthine streets hinting at secrets lurking deep down the twisting alleyways or behind closed, tracery-adorned doors.

Despite the challenges brought by centuries of over-tourism – crowds, tacky souvenir shops, gruff waiters and pickpockets – along with the city’s famously sinking ground levels (these exacerbated by flooding caused by acque alte, exceptional tide peaks that are occurring increasingly frequently in the northern Adriatic Sea as a result of rising sea levels), I’m still awestruck by Venice. Its nickname ‘La Serenissima’ may be a misnomer these days, yet I somehow manage to airbrush out the throngs of tourists, imagining it as in Roeg’s film and in more recent, pandemic times, stripped to just 50,000 inhabitants (its citizens equating to just 0.2 per cent of the annual tourist population). I’m still excited by getting lost in its maze of unmarked streets, the serenades of gondolieri in their stripy jerseys, the flash of a gondola’s golden fero da prorà (iron prow head) bobbing into view, medieval church bells and even the waters’ pungent Adriatic tang.

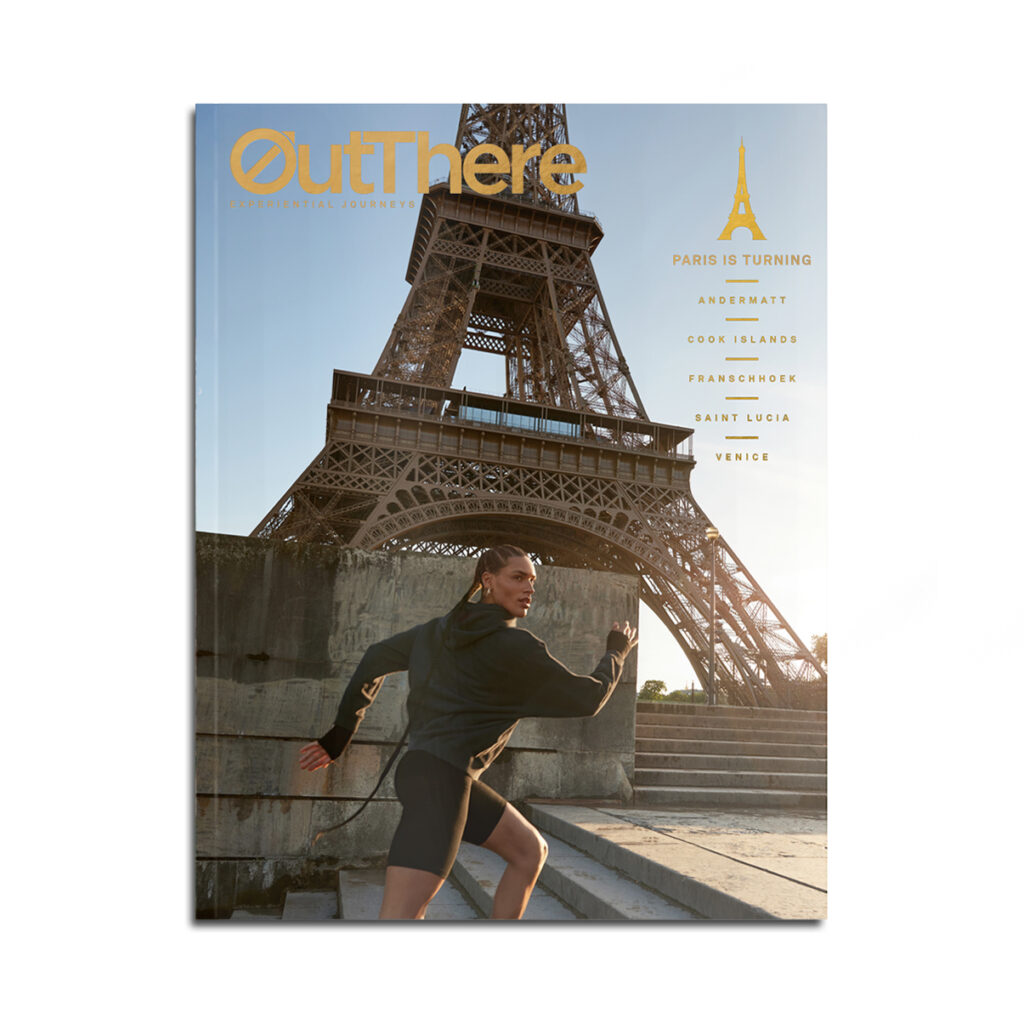

This story first appeared in The Paris is Turning Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

And Venice is working hard to redress the balance. A systemic clampdown on Airbnbs in the historic quarter, a cruise-ship ban in the central lagoon, a controversial day-tripper’s tax and more sustainable management practices have all begun to remake the city’s tourism landscape. The pandemic also gave those working in hospitality a more nuanced appreciation of their symbiosis with tourism. Service overall is much better today – and, with Italian-speaking Bangladeshi and Chinese migrants now fronting many of the city’s restaurants, more diverse than it has ever been. No one gives a second glance when LGBTQ+ couples share a romantic gondola ride, and transgender gondolieri such as Alex Hai and Edoardo Beniamin are now part of the hallowed millennia-old profession.

There are even TikTok-famous ‘vigilantes’ who repel would-be purse-snatchers with shouts of “Attenzione! Borseggiatrici! Pickpockets!”. It seems Venetians have finally accepted that better tourism has to be a win-win.

An exhibition of itself

Meanwhile, a new and future-facing energy is revitalising the city’s cultural life. It’s arguable that in the late 19th century an already beleaguered Venice safeguarded its future by reinventing itself as the world’s premier event space. Since the inaugural art exhibition in 1895, the city’s prestigious biennales – today encompassing separate international events for architecture, film, dance, music and theatre – have celebrated creative excellence while challenging conventions and showcasing bold innovation. They bring together outstanding talent from all over the world, playing on Venice’s history as the gateway between East and West, a then-unrivalled hub of routes of trade and cultural exchange. But, aside from the historic art treasures and architecture that make it uniquely qualified to host such ambitious events, Venice is now also increasingly flexing its muscles as a generator-exporter, buzzing with local creative leaders and social entrepreneurs eager for their achievements to be recognised.

Fondazione di Venezia has been the nerve centre of this revival, collaborating with the philanthropic Berggruen Institute to convert the striking, neo-Gothic Casa dei Tre Oci on the southern Venetian island of Giudecca into a world-class creative hub that plays host to an international programme of exhibitions, symposia and workshops focused on visual arts and architecture. Sister site Berggruen Arts & Culture, meanwhile, in Cannaregio’s Palazzo Diedo, places specific emphasis on art physically made in Venice.

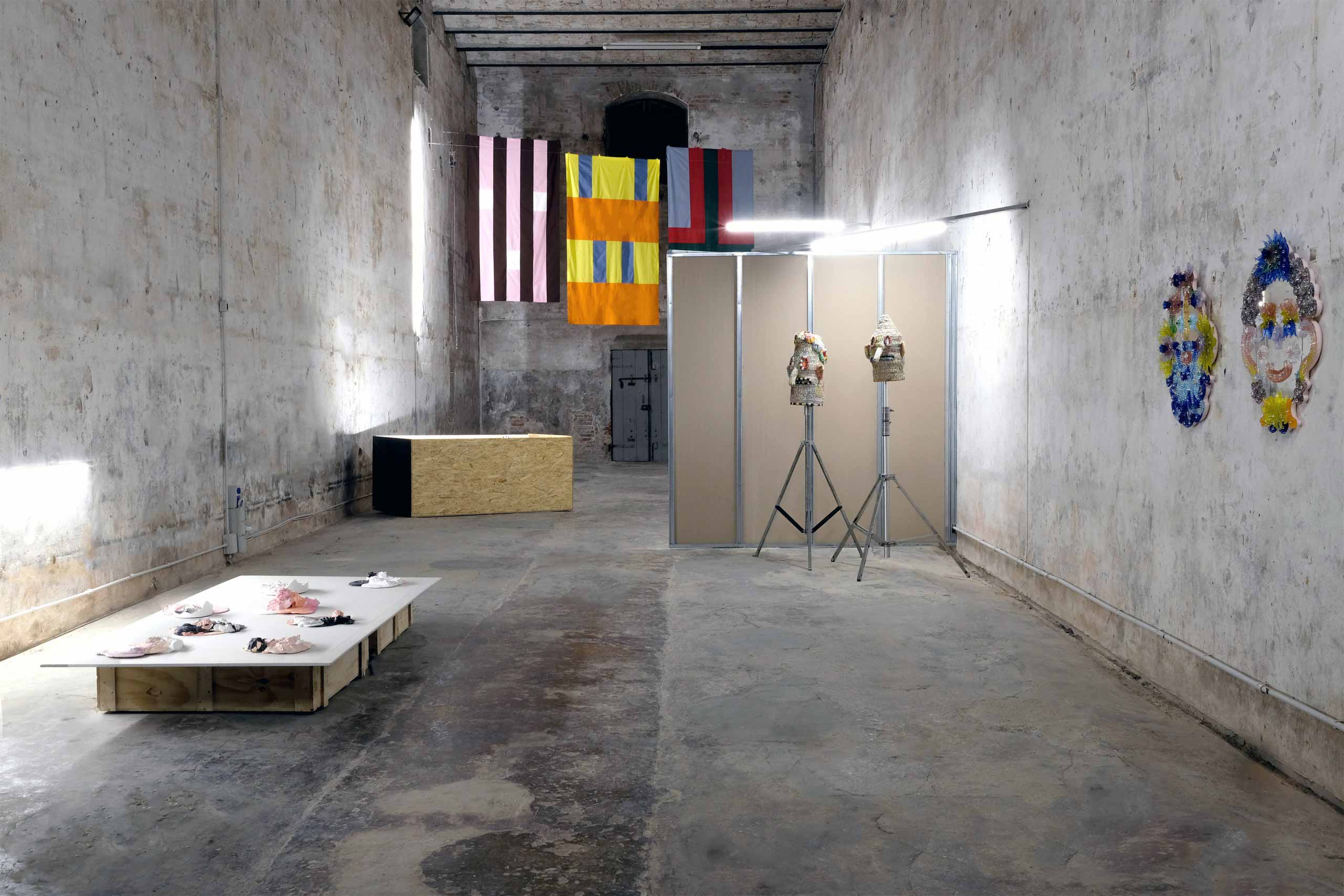

I walk along Giudecca’s Fondamenta San Biagio waterfront to Spazio Punch (pictured, right), a self-billed ‘underground institution’ and not-for-profit art, fashion, publishing and architecture space founded in the former Pizzolotto liquor brewery by celebrated local video and collage artist Lucia Veronesi and current creative director Augusto Maurandi. The curation here is fascinating and the gallery, which is intrinsically connected to the Biennale Arte, also collaborates with local universities and academies to nurture homegrown talent.

Other ambitious Venetian-born cultural projects are in the making, linked to other biennale strands. Opening in 1637, Teatro San Cassiano was the world’s first public opera house, democratising Baroque musical performance – once reserved for the aristocracy – by bringing it to the bourgeois public. It also has an LGBTQ+ history – in the 18th century male courtesans were known to cavort with queer aristocrats in the fifth-tier boxes, then the opera house was demolished in 1812. A project is underway to reconstruct it elsewhere in the city as a world centre for the research and study of Baroque opera and as a unique space offering ‘historically informed performances’ alongside contemporary-music programming – all of which will be streamed online. The project is expected to be completed by 2028. The scheme’s leaders hope to replicate the success of projects such as London’s Shakespeare’s Globe while promoting Venetian music.

Their dream location, I’m told, is behind Palazzo Donà Balbi, right on the Grand Canal, between the train station and Rialto. A key collaborator is VeniSIA, the city’s new sustainability innovation accelerator, whose trademarked slogan is ‘Venice, the oldest city of the future®’.

Contemporary music and performance art are seeing a renaissance, too, with the Biennale Musica increasingly spotlighting electronic and digital music and AI. Traditionally overlooked by tourists, mainland Marghera, part of the Metropolitan City of Venice, is powering a burgeoning, local, alternative-music scene in venues such as Area City, Goorilla and Molocinque. I visited Centro Sociale Rivolta, a former spice factory in a street-art-rich industrial neighbourhood. Surrounded by disused railway tracks and shipyard cranes, it has become the spiritual home of anti-establishment music and performance. It was from here that the successful ‘cruise-ship ban’ protest was orchestrated. Marghera is now home to a tight-knit community of creative Venetians who left the historic part of the city because of soaring rents, and the shoots of gentrification are already showing. But for now, Marghera feels somewhat more Venetian than Venice itself.

And while island Venice isn’t going to win any prizes for visibly progressive queer culture, its lack of LGBTQ+-designated venues reflects less a lack of acceptance and more how integrated queer identity has long been within Venetian life. This is no great surprise, given a history that includes male (for male) courtesans, a secret society of gondolieri who allowed same-sex lovers to frolic in their boats after dark, Carnival cat masks that allowed gay men to identify each other in plain sight and three years as the adopted home of Lord Byron, the poet and queer travel influencer at the start of the 19th century.

A significant gesture, however, came in 2007, when the Venice International Film Festival, one of the world’s big-five moving-image kingmakers, introduced its annual Queer Lion trophy for best film with a central LGBTQ+ theme. And June sees the cityscape that was the setting for the tragic gay novella and movie Death in Venice host some happier LGBTQ+ stories, in the annual Laguna Pride parade and arts, sports and entertainment programme.

The new design disruptors

I continue my quest for the new on a private tour of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi department store – Venice’s equivalent of Liberty in London and Bergdorf Goodman in New York. A vast, 13th-century live/work space for German merchants, rebuilt in the 16th century after a fire, the building’s extraordinary architectural fusion today integrates spectacular contemporary interiors and structural elements by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and his international practice, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. Here, I discover Barena Venezia, a local brand founded in the early 1960s by Sandro Zara. Not typically Italian, Barena Venezia features simple wardrobe essentials made from sumptuous fabrics. Today, Sandro’s daughter Francesca has evolved the brand for the next generation, embodying its original spirit, but adding contemporary elements brought home from her work as a textile designer in New York and Copenhagen.

More Venetian fashion innovation making worldwide waves can be found at Venice M’Art, a contemporary and cutting-edge concept store, bar and restaurant. It’s part of The Venice Venice Hotel, a hospitality, retail, art and culture complex that has set tongues wagging, and the brainchild of two of new Venice’s poster children, husband-and-wife designer duo Alessandro Gallo and Francesca Rinaldo, founders of homegrown, handmade sneaker brand Golden Goose. The label trades on perfect imperfection, its artistically distressed sneakers costing far more than brand-spanking-new ones – and it’s wildly popular planet-wide. I find this an apt allegory for the Venice I’m slowly discovering – full blooded contemporary non-conformity reinterpreting traditional Italian values of centuries-old craftsmanship.

The couple last year announced a new concept called Haus of Dreamers, a global platform and creative incubator that will create a 2,000 sq m/22,000 sq ft campus and school for artisans, with library, design archive and exhibition area: ‘a community for dreamers,’ in their words. Where, you ask? You guessed it, Marghera… where Francesca and Alessandro are from.

Even Murano’s eponymous and 12-centuries-old glass industry is undergoing a quiet revolution. Today, many of the island’s most established glass studios are collaborating with contemporary artists – as I discover at Berengo Studio, which counts Ai Weiwei and Tracey Emin among its co-creators. Also on Murano, Orovetro has launched Good Vibes on the site of its 15th-century heritage furnace, a new venue for music, cuisine and entertainment, offering immersive and live events. El Cocal Glass Studio, meanwhile, was female-founded in 2021 and trains only women glassmakers, typically to a banging technopunk soundtrack.

As I ride the ferry back from Murano, I question if my eyes deceive me at the bizarre sight of spaceship-like vessels floating on the lagoon. These futuristic boats, I later discover, are heading to the Grand Canal, led by the RaceBird, the world’s first all-electric hydrofoil raceboat, to compete in the Union Internationale Motonautique’s UIM E1 World Championship, the first-of-its-kind electric-raceboat regatta.

I once loved Venice for all that is anachronistic about it, and, of course, it looks and feels as it has across the centuries. But my eyes have been opened to a new, emerging city that puts me in mind of the Venetian saying ‘te si na bronsa cuerta’ (you are like embers covered by ashes). Its meaning? While appearances seem calm, something frisky brews beneath.

Photography by Luca Bravo, Rebecca Ann Hughes, and courtesy of El Cocal Glass Studio, Berengo Studio, Golden Goose, Spazio Punch. Performance artwork by François Dallegret

Get out there

Do…

… stream Don’t Look Now for a taste of Venice in the 1970s. For a more contemporary but equally filmic take, the Netflix series Ripley also portrays the city beautifully with a similarly chiaroscuro aesthetic.

… book a private boat ride with transgender gondolier Alex Hai for a queer spin on the centuries-old tradition. Their beautiful gondola Pegasus seats four and they offer LGBTQ+ tours daily. Book well in advance.

… pick up a souvenir at Kooch, which sells the work of Iranian artisans, who have a long history with Venetian glassmakers. En route to Persia, much cargo broke, but the gorgeous objets d’art created from the shards were sent back for sale – at a premium.

Don’t…

… overlook the city’s culinary renaissance. Oliva Nera is fantastic, with its fiori di zucca a must-eat. There’s also Koenji, an Italo-Japanese fusion osteria where it’s almost impossible to get a table, so book ahead.

… be afraid to push your boundaries. The jewel-toned Experimental Cocktail Club is a brilliant contemporary place to have a bespoke aperitivo and cicchetti (tapas).

… stay on the shop floor at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi. The building’s new 360º panoramic terrace – an homage to the traditional ‘altane’ sunroofs found on the rooftops of Venetian homes – gives breathtaking views over the city.

The inside track

Venice Venice Hotel manager Simone Cherin heads up ‘The Dream Builders’, a guest-relations team who are always ready to help visitors make Venetian dreams old and new come true.

Read

Created in collaboration with French textiles house Métaphores, Libreria Rupture Arts and Books is a unique and extraordinary store offering a curated selection of books, objects and artworks. I love browsing the shelves here.

@libreriarupturevenezia

Gaze

Giorgio Mastinu Fine Art, on Crosera de le Botteghe, in San Marco, is a private Venetian gallery, where the rare artworks on display are handpicked by Giorgio himself, the result of tireless personal research. He has fantastic taste. @giorgiomastinu

Wander

Redefine getting lost in Venice with a visit to the Labirinto Borges, a stunning maze in the ancient monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. Architect Randoll Coate designed it in tribute to writer Jorge Luis Borges. www.visitcini.com