Half palatial splendour, half crumbling ghetto, Budapest’s District VIII is home to a network of grassroots venues that provide social spaces, entertainment and intellectual engagement to a creative countercultural community bent on resisting its government’s illiberal agenda with art, activism and inclusivity.

The taxi driver’s salacious raised eyebrow in the rear-view mirror came as something of a surprise. All I’d said was “Rákóczi Square, please”.

“Old prejudices die hard,” laughed my friend Miklós, a long-term local resident, when I reached my destination. “For decades this was a very shady area and a front line for prostitution.”

One of the biggest of Budapest’s 23 neighbourhoods – and its most diverse – District VIII, aka Józsefváros, presents a fascinatingly contradictory aesthetic that manifests its turbulent history. To the west of Grand Boulevard, elegant city streets are punctuated with opulent 19th-century mansions and landmark historic buildings (some still bearing bullet wounds from the 1956 revolution) that have earned the area the nickname the Palace Quarter. To its east, scruffy apartment buildings stained tobacco-brown by urban pollution are the norm. Many are in sore need of repair, while occasional outcrops of towering glass and steel bear witness to the major regeneration programme in progress.

On one such street, in a gap between terraces of shabby once-handsome residences, stands an undistinguished dusty-terracotta-painted house known to locals as Auróra. A door leads to a courtyard and bar furnished with flea-market finds and fairy lights, where a mainly youngish crowd sip cheap beers and chat animatedly. They are hipsters, professionals, creatives, straights, gays and members of some of District VIII’s many ethnic communities. The mood is relaxed, friendly and effortlessly inclusive.

Known variously as a community space, cultural centre and NGO hub, Auróra is one of a handful of places in District VIII that perform a vital and embattled function in the city. Using revenue from its bar to subsidise in-house office rents for a range of nonprofits working to support marginalised social groups, it’s also a grassroots cultural hub, hosting gigs, film screenings, parties and theatre performances, usually with a progressive political edge, and it’s locked in an ongoing battle for survival with ruling authorities.

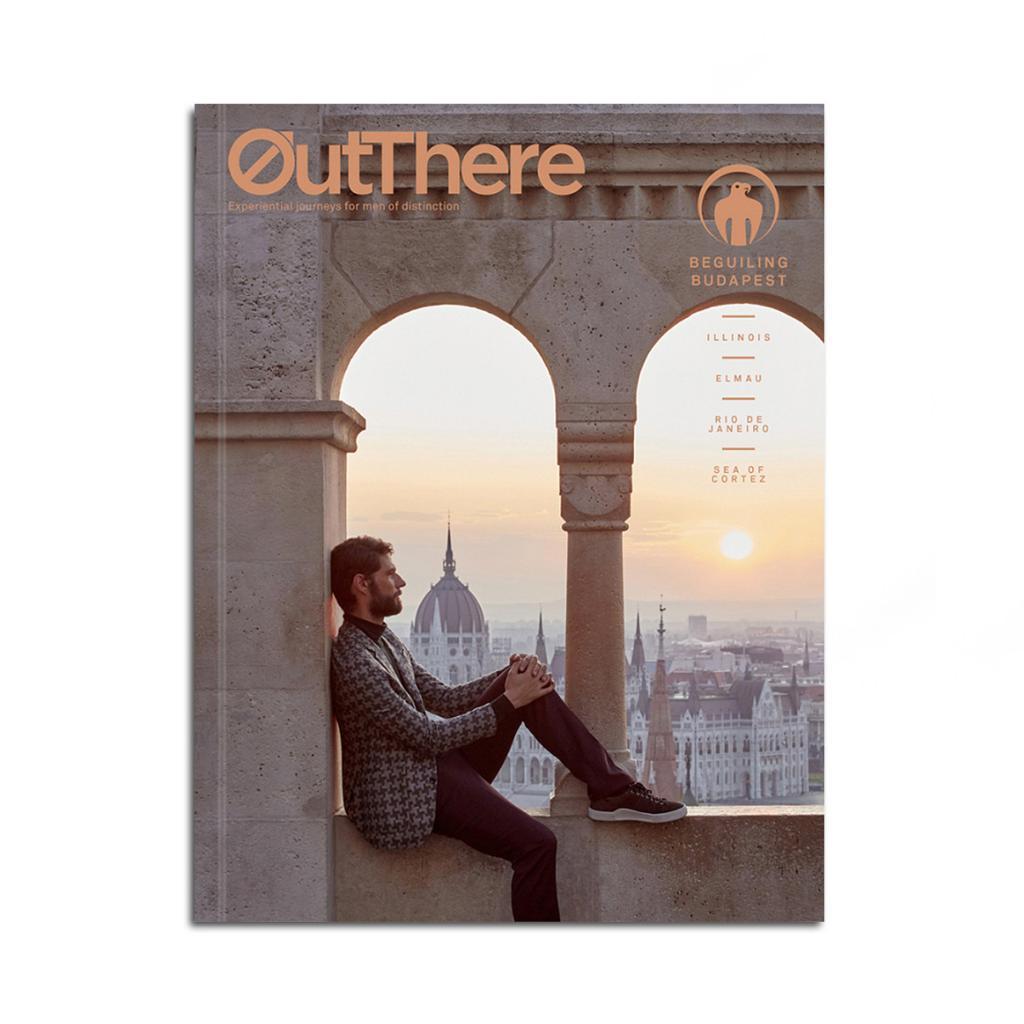

This story first appeared in The Beguiling Budapest Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

“Our audience is made up of open-minded, socially responsible citizens, international students and expats who don’t subscribe to our government’s ideology and want to see Hungary change,” says Daniel Mayer, a volunteer member of the collective that runs the space.

“In recent years, we’ve seen a crackdown on democracy and growing attacks on civil society and on minority groups in particular. Our guests want to collaborate with like-minded people to challenge this, whether by taking part in cultural or political events here or simply exchanging ideas over a drink.”

On my first visit to Budapest three years ago, a young local artist introduced me to Auróra, as well as to several other similarly intersectional spaces nearby rolling out experimental, socially conscious agendas. I found their spirit of communal can-do and creative DIY aesthetics thrilling. Returning this spring, I was saddened to find many had closed, notably the remarkable Müszi, a broad alliance of artists, architects and activists occupying a whole disused storey of a Communist-era department store, and Corvintető, the rooftop techno club above it. (Both outfits continue to operate, in less radical form, elsewhere in the city.) One reason for their closure is the soaring real-estate values in a neighbourhood earmarked for relentlessly commercial regeneration. Another, as multiple spurious police raids on Auróra attest, is a governmental clampdown on dissent many are calling Prime Minister Orbán’s ‘Kulturkampf’. A third is the steady stream of dispirited young and forward-thinking people leaving the country in dismay at its political direction.

“Our leadership hates Auróra to its guts,” says Viktória Radványi, who, as communications coordinator for Budapest Pride, one of Auróra’s resident NGOs, plays a key role in the annual month-long festival that culminates in July’s parade. “Jews, gays, Roma people, environmental activists… All the minorities they wish would just shut up and be invisible, together in one place.”

It’s a climate that calls to mind ‘the three Ts’ of Hungary’s old Communist cultural policy, which designated organisations ‘támogatott’, ‘tűrt’ or ‘tiltott’ (supported, tolerated or banned). For now, and thanks in large part to crowdfunding after the local government stopped its vital bar sales after 10pm (events and socials at Auróra routinely go on until 3 or 4am at weekends), Auróra continues to resist the various attempts of an administration reluctant to prohibit it outright to starve it of oxygen.

“Auróra’s low rents allowed us our first-ever office, instead of holding meetings at this or that member’s flat,” continues Viktória. “We can also use the shared spaces for screenings, talks and social events all year round, when most venues are afraid to hire to LGBTQ organisations because of the political climate. And sharing the building with other NGOs with values and goals in common means we all help each other out. Which makes us all more effective.”