Non-believer Zack Cahill makes a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

No place on this earth – with the possible exception of a Michael Bolton concert – makes you question the nature of your existence like Jerusalem. It challenges your morals, your beliefs. Like a theological night-club bouncer, it grabs you by the collar and demands to know why you’re there.

I know why I’m here. It seems that despite lifelong atheism, the older I get, the more fascinated I become with ritual and the more I long for some kind of faith. It’s mostly because I have an almost pathological fear of death. The 20-year-old me would be aghast. An insufferable dinner party agitator, citing Hitchens and Dawkins at anyone who dared mention something as innocuous as horoscopes, he would shudder to think that 14 years hence, he’d be on a pilgrimage in the City of David to the site of Christ’s crucifixion (or at least allegedly – more on that later).

In a day already crammed with history, we figure to squeeze in a little more on the way. Frankly, most visitors would spend days, sometimes months, even years, feeling their way through Jerusalem, but today, we are on a whistle-stop tour, with our hosts, Pomegranate Travel trying to give us a taster for the city in just one day. We start at the Knesset, just to put the very existence of Israel and its complicated politics into context, and already it feels like information overload.

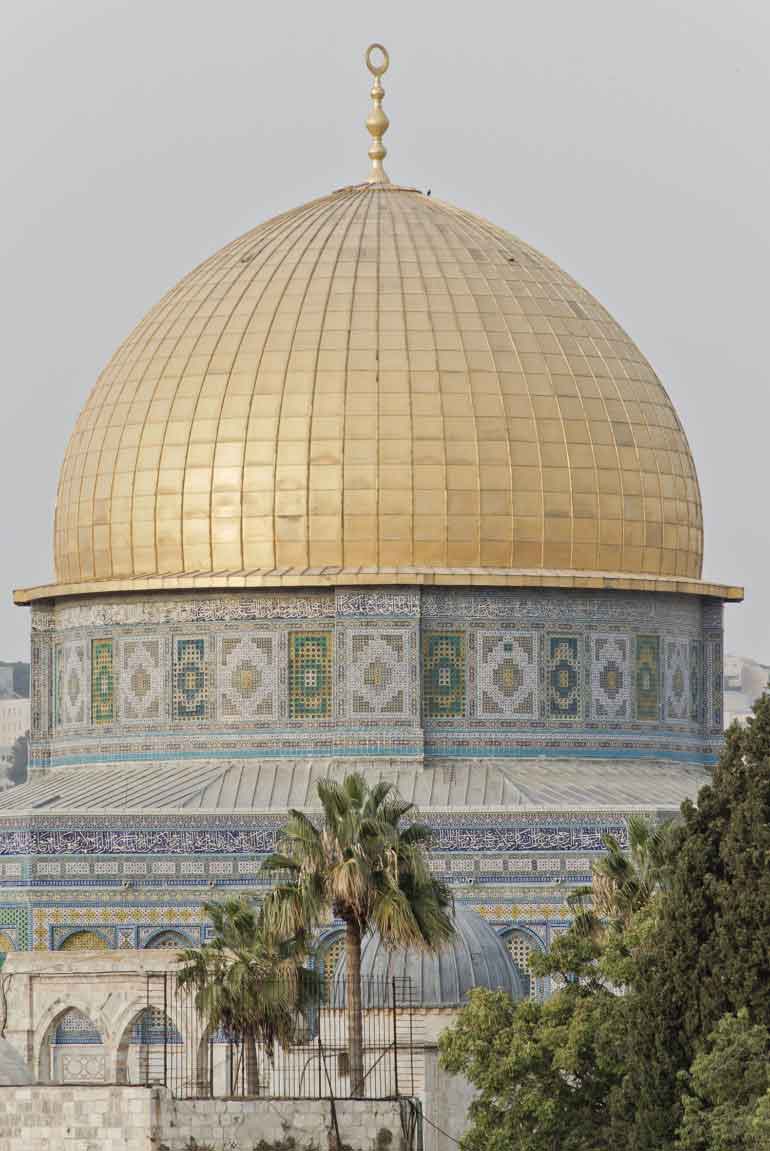

Downhill, at the impressive Israel Museum, I’m a guinea pig on a new tour that’s all about the Israeli male body image, put together by one of the museum’s gay, senior guides. Pomegranate Travel had done a wonderful job in creating a tour of Jerusalem suited to my tastes, but while an interesting concept, even the guide professes that the theme is a difficult thing to shoehorn into a widely diverse collection. I am impressed at what he’s trying to tell me, but frankly, I’m much more interested in getting to the Dome of the Book; a bizarre, onion-shaped building, nightclub-lit and air-conditioned – home to the Dead Sea Scrolls. I scan the ancient pages, pulled from a cave after a thousand years; the Hebrew still perfectly legible to any Israeli school child. It makes me think of the very book that dominated my 18 years of Catholic school in Dublin: its protagonist staring grimly down at us from his wooden cross above the blackboard; the Hail Marys we recited in Irish every time a teacher entered or left the class.

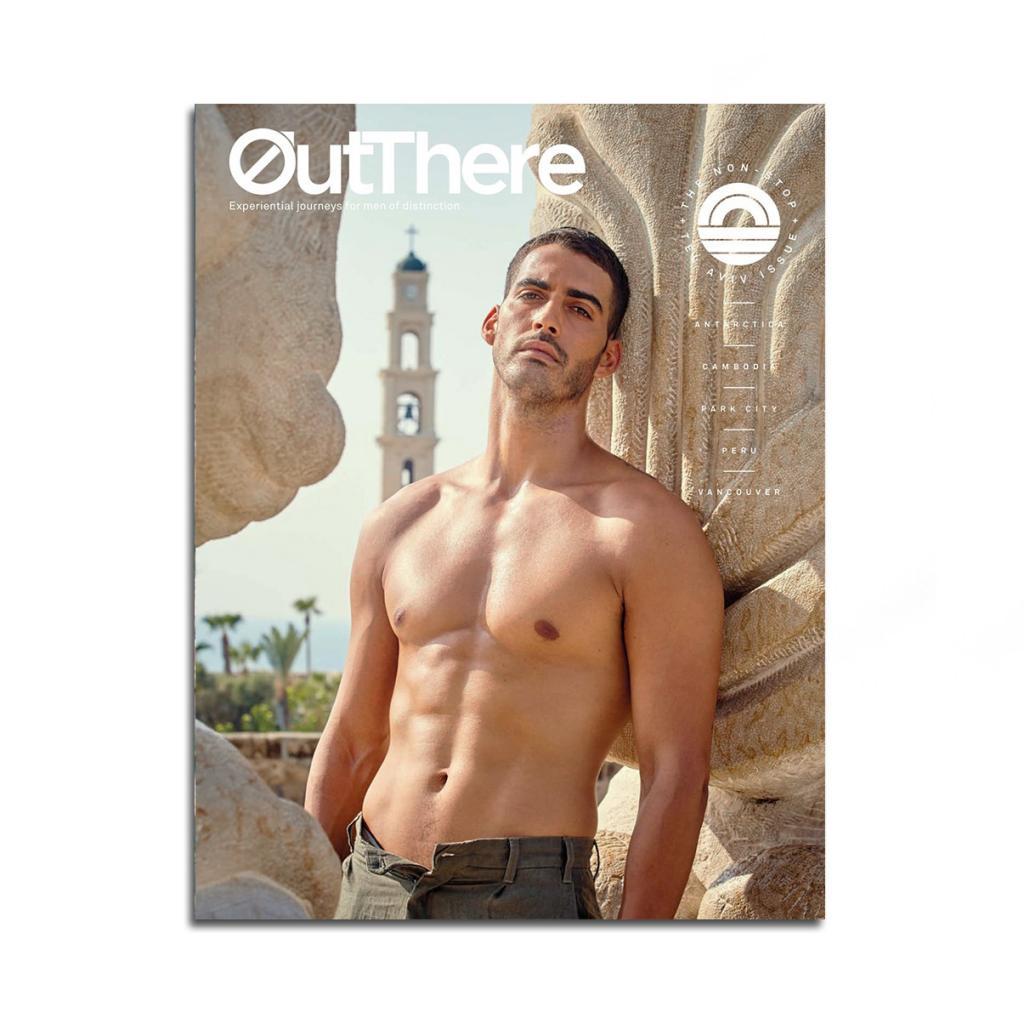

This story first appeared in The Non-Stop Tel Aviv Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

I recently told a London friend some of my Catholic school stories. I presented them as amusing anecdotes. When I finished, I realised her mouth was hanging wide open as if I had described some mad alternate reality.

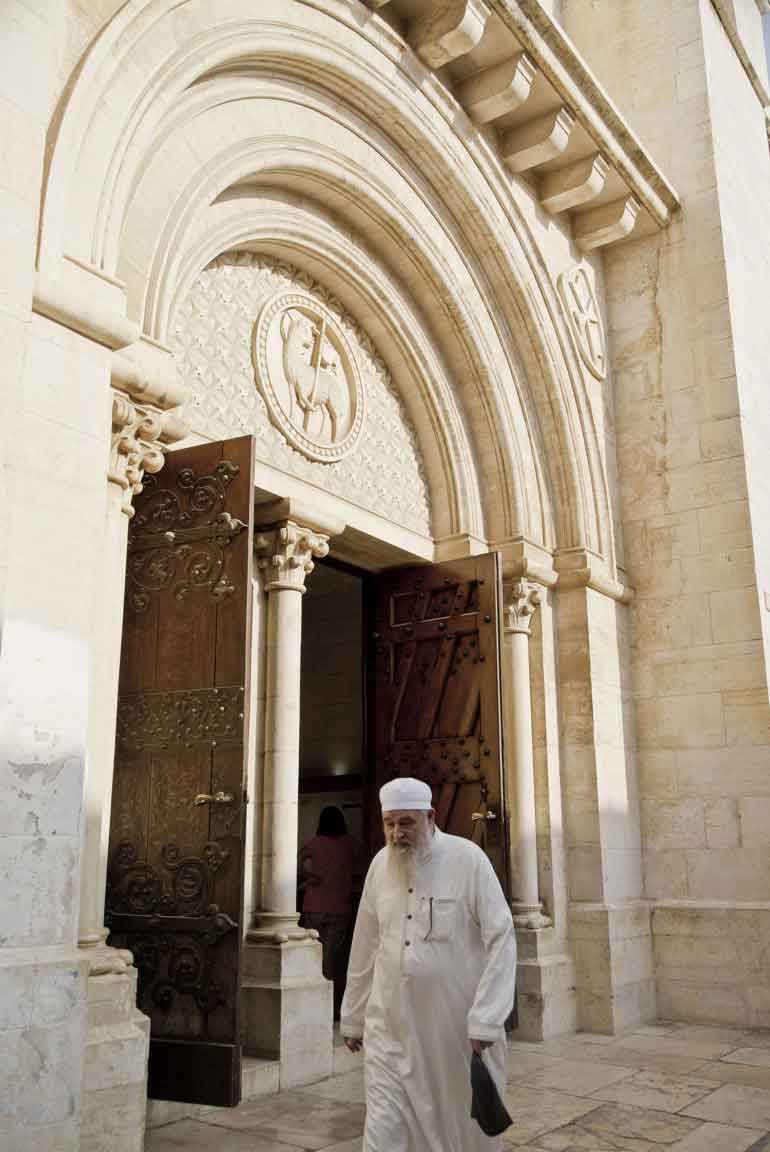

I’ve been reminding myself of that, every time I see a member of the Orthodox sect, heavy black coat and hat in forty-degree heat, or the man I saw on the plane over, with the strange box strapped to his head, its leather straps coiled around his arm, rocking and praying. To me, all religions look strange from the outside. Although my Pomegranate guide for the day, Jeremy – a British Jewish transplant – begs to differ. To him, even after a decade of living in Israel, it looks strange too. As we walk quickly through the bustling, heaving Mahane Yehuda Market to see it in a quick half-hour, supping craft beer, halva and a bowl full of hot hummus in the process (another excursion that could easily take a half day), he rattles off an abridged history of the Jewish faith.

“Up until about 250 years ago, everyone agreed who the Jews were – a displaced people who originated in Israel. Then after the enlightenment, there was a push towards reform.”

As tends to be the case when you try to reform any kind of religion, whether you’re hammering theses to a Church door or suggesting maybe gay marriage is okay, there were a few holdouts. Those who resisted the reformation became known collectively as Orthodox Jews. That’s the hat, coat and curly hair brigade we see as we arrive at the old city, that we didn’t see so many of in Tel Aviv. But, as Jeremy points out, they’re not one, homogenous mass. There are thirteen different kinds, each with their different convictions, all existing on a sliding scale of conservatism. Jeremy can pick them out by the shape of their hats, the colour of their jackets; like an expert gardener pointing out exotic shrubs when all I can see is grass.

“Anyone who says they understand Jerusalem, really doesn’t at all.”

We enter the great gates of King David’s ancient city and huddle in the shade, as a UN convention of visitors pour ahead – Swedish, Chinese, American, German, among others. Jeremy tells us a number of conflicting stories about the architect who built the city in 1538. First, he says the architect was so honoured to have built the city that he asked to be buried here, beneath our feet. Then he says that he was buried here as punishment. He presents each story, each version, as fact. The point being if someone tells you something definite about this place, they don’t know what they’re talking about.

“And anyone who claims that they understand Jerusalem, doesn’t understand Jerusalem at all,” he adds.

Over a scale model of the city we map out the path we will take, first through the Jewish, then the Muslim quarter. The other two are Christian and Armenian. The quarters are incredibly well defined. You can be bobbing and weaving past the wide-brimmed hats and shops selling menorahs, ducking under the parasols of Chinese tourists, then slip through a side street and suddenly you’re transported to an Arab souk as if you’ve stepped through a magical portal. Heaving stalls selling dates, pistachios and endless gaudy tat line the narrow streets, and the inevitable calls of “Hello, English?!” ring in your ears.

I’d been chastised for the shortness of my shorts on a recent trip to Angkor Wat and here again, we receive a number of scornful glances and tuts from the conservative populace. A man mutters something under his breath and our guide barks back a reprimand in his fluent phlegmy Hebrew – a language I have singularly failed to develop any kind of an ear for, its spitty syllables turning to candy floss in my mouth.

The Western Wall is only sacred because it’s the closest point you can get to another sacred place, Mount Moriah, where Adam was created. It is the primary visual touchstone for anyone trying to picture Jerusalem – the lines of people in kippahs, bowing in jerky movements, laying their hands lovingly on the ancient edifice, posting letters in the cracks. You’re not supposed to write a wish, it turns out. You’re supposed to be thankful for something. So I write a little heartfelt screed about my friends and pack the letter into an already heaving crevasse.